A new publication brings to light a group of Sol LeWitt’s (1928-2007) works that have, until now, received little attention. The late US Minimalist and conceptual artist began visiting Italy in the late 1960s, later moving to the central Umbrian town of Spoleto. In 1976, LeWitt made a large group of pencil drawings on the internal walls of the Vecchia Torre, a medieval tower in Spoleto that became his studio during his Italian sojourn. “These fragile drawings, made on walls that are susceptible to degradation, have rarely been seen and never been documented, yet they represent one of LeWitt's major works,” says a statement from MIT Press, the publisher of a new book about the works. In the extract below, the art historian Rye Dag Holmboe outlines the significance of the tower drawings, how they elucidate LeWitt’s work-in-progress approach, and how some of these key works were almost lost.

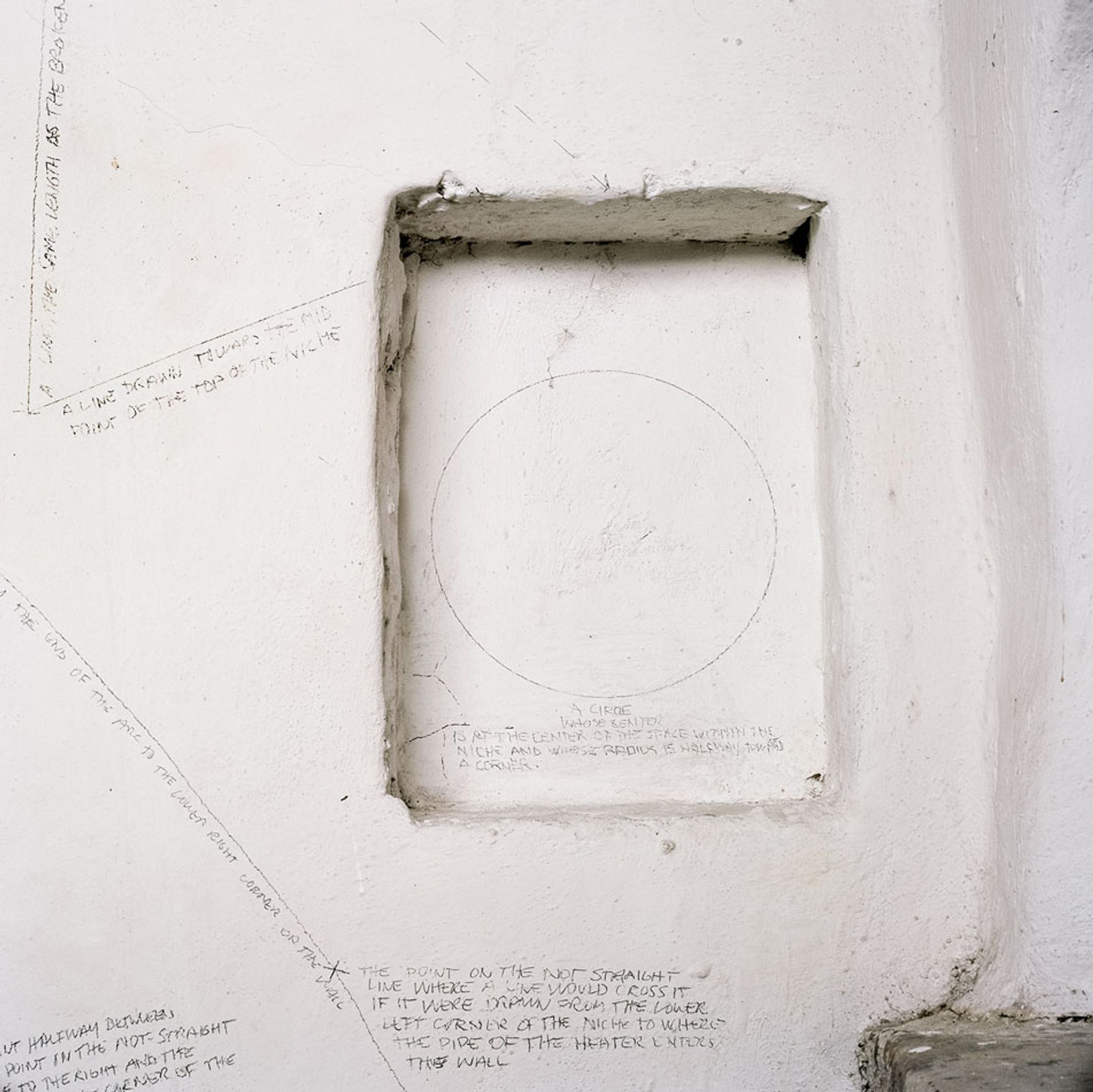

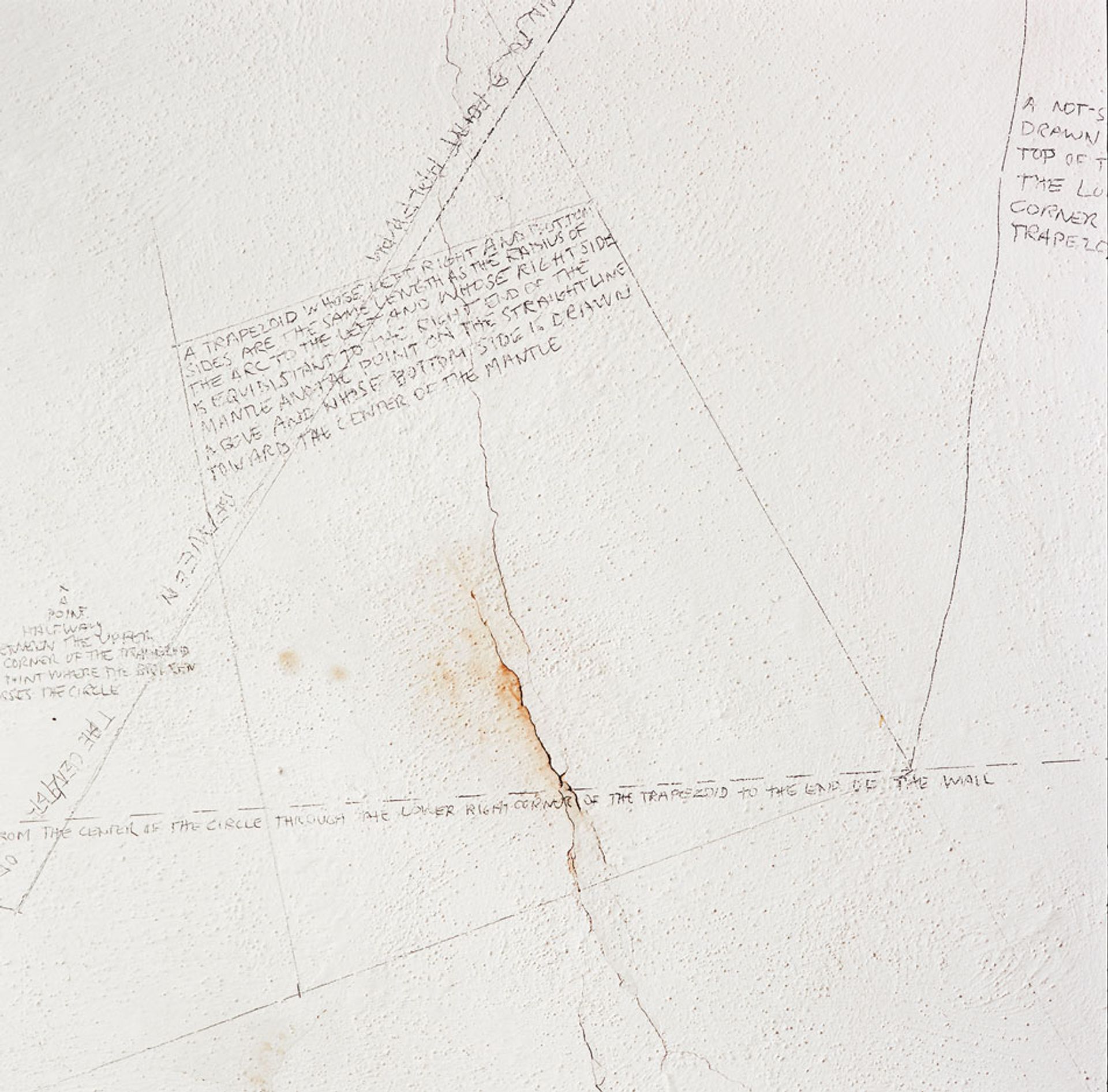

In 1976, Sol LeWitt produced a group of wall drawings in the Vecchia Torre, a medieval tower in the Umbrian town of Spoleto, Italy. They comprise an elaborate series of line, shape, and word drawings, three grids in which different combinations of geometric figures are exhausted, and a statement that reads, tautologically, “ON THIS WALL ONE FINDS THIS WRITING.”

At the time, LeWitt was staying with two friends, the gallerist Marilena Bonomo and her husband, Lorenzo, at their converted Augustinian hermitage on Monteluco, a nearby mountain. LeWitt grew to love Spoleto and moved there permanently in 1980; a number of his works can be found around town, in parks, restaurants, and cafes, where they were sometimes exchanged as gifts.

Marilena and Lorenzo first asked LeWitt to make a number of site-specific drawings in their home, a complex series of intersecting circles made with pencil that exists to this day. This work speaks to LeWitt’s explorations of seriality and the use of rules when making art. He made another wall drawing with his friend, the artist Mel Bochner, who often visited Spoleto. The town became a meeting place for a number of artists, largely because of the Festival dei Due Mondi. The Bonomos would later have works made by LeWitt’s friends Alighiero Boetti, Richard Tuttle and David Tremlett on the walls of their 13th-century hermitage.

Sol LeWitt’s drawings on the walls of the Vecchia Torre, Spoleto Photo: Joschi Herczeg

During his stay in Spoleto, the Bonomos invited LeWitt to use their medieval tower as a studio. Each day he made his way there on foot, setting out at 7am and meandering along the mountain paths crisscrossing Monteluco, sometimes photographing what he saw en route. He then walked the length of a beautiful aqueduct, the Ponte delle Torri, more than 200m long and 90m high, which connects the mountains to the town. The tower is just a short walk from the Piazza del Mercato, the main square in Spoleto, where LeWitt took coffee and read a copy of La Repubblica, learning Italian as he went. He also wrote a number of postcards that he sent to family and friends.

The drawings from 1976 are not the only ones he made on the walls of the tower. One year later, in 1977, LeWitt produced a further series of drawings for an exhibition in the Vecchia Torre, one of several shows held there between 1976 and 1993. Since the exhibition was temporary and site-specific, some of these drawings were soon covered up. A large circle made in black charcoal, which formed part of a series of six geometric shapes drawn directly onto the tower’s white plastered walls, is now barely visible beneath a brightly coloured abstract painting by the Italian artist Nicola de Maria. Two other drawings from this series, a trapezoid and a parallelogram, were painted over in white so as not to distract attention from the works of future artists.

The pencil drawings made in 1976 are different from the 1977 series because they were not initially meant for public viewing. For some time they were shared only by other artists invited to take up residence in the tower. They are more provisional and exploratory, and might better be termed studio drawings, or “studiowork”. This is the expression used by the art historian Briony Fer to describe the objects left behind in Eva Hesse’s studio after her death in 1970, objects that were more provisional and difficult to define than her finished work.

LeWitt’s drawings Photo: Joschi Herczeg

What also make the 1976 drawings singular in LeWitt’s oeuvre are their fragility—the crumbling plaster means that they have slowly degraded, a situation not helped by Spoleto’s susceptibility to earthquakes—and the fact that, unlike so much of LeWitt’s work, they are not reproducible. Or at least it is very difficult to imagine how they could look or feel the same anywhere else. One of the most striking aspects of the studio drawings is the way they reveal LeWitt’s makeshift, trial-and-error working method. The attempt to exhaust every combination of six geometric figures in the three grid drawings took several tries. An ostensibly simple problem found no ready solution, and the orderly aspects of the drawings are belied by the many mistakes and erasures he made when trying to create them. The grid drawings act as a rejoinder to those who would see LeWitt’s geometric work as mathematically or aesthetically pure. The process of making is too messy, too filled with errors, and too playful. The basic shapes are closer to children’s building blocks than they are to geometric essences, even if these are also evoked.

• Sol LeWitt's Studio Drawings in the Vecchia Torre, Rye Dag Holmboe, MIT Press, 136pp, $49.95 (hb)