On 14 October 2022, after 19 days of picketing through rain and sunshine, my colleagues at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) ended our historic strike. The union contract we won guarantees 14% pay increases over the life of the three-year agreement, decreases the cost of our health insurance and allows for four weeks of paid parental leave, among other improvements that were years in the making.

Since our strike ended last October, workers at the Please Touch Museum in Philadelphia, the Wexner Arts Center in Ohio, the Storm King Art Center in New York and the Field Museum in Chicago, among others, have all won union elections. University workers at Temple University and Rutgers University have also held successful strikes in their fight for a living wage and better working conditions, while some, like the Hispanic Society Museum and Library in New York, remain on strike as of this writing. As we see more labour organising across the museum world and beyond, here are four of the things I have learned at the PMA that I want to share with my colleagues across the world of arts, culture and education.

Precarity anywhere hurts workers everywhere

I was hired as an educator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2014 after going to graduate school in New York. I loved teaching, but I hated the hustle of adjunct instructing and craved a greater sense of job security.

Museum education seemed like a dream. During the weeks-long interview process, I never broached the subject of compensation— I was just happy to be considered. When I was finally offered the job, the hiring manager said something along the lines of, “We don’t do this for the money,” and offered me $40,000 a year. I accepted without negotiating. Nine years later and amid record inflation, there are still people working full time at the museum who make less than that.

Change starts with talking to your co-workers—all of them

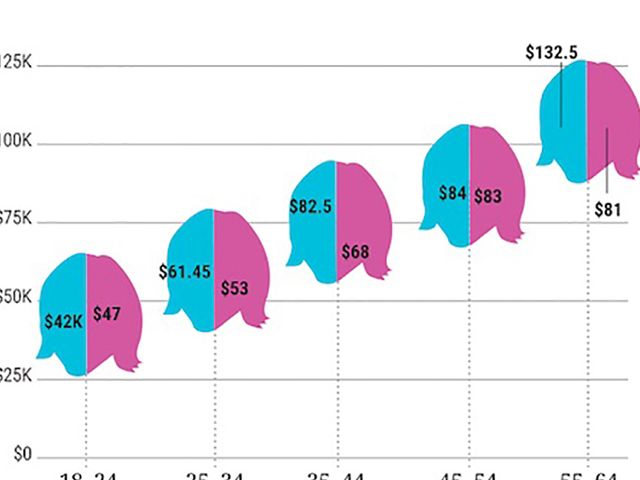

In 2019, a group called Art + Museum Transparency launched a salary transparency spreadsheet. Museum workers anonymously shared information about their salaries and benefits. It was eye-opening for me. I learned that my colleague, who held the same title as me and had more museum education experience, was making about $7,000 less than me a year. I am a man and she is a woman. The more we talked frankly to one another, not just within our department but across teams, the more inequities became clear.

In large museums, different departments are often isolated from one another. This makes it easier for abusive managers to maintain power, as we experienced more than once; it also makes it harder for workers to see the many issues they have in common. As we started talking about a union, we saw that curators, educators, front-of-house staff, art handlers, fundraisers and others were all overworked, underpaid and being treated as disposable. When we filed for our union election, we did so as the first wall-to-wall bargaining unit at a major museum in the United States, and we went on to win our election by 89%. That unity wasn’t just a moral victory; it meant that when we went on strike, we had a massive impact. And when we were on the picket line, we built incredible relationships across departments that will sustain and inform us going forward.

The boss is the best organiser

Anyone familiar with union-busting tactics will recognise the tools that our senior executives and Morgan Lewis, their “union avoidance” law firm, used throughout the process: casting the union as a third party instead of their own employees, sending weekly emails mischaracterising the state of negotiations and raising wages for non-union employees only.

However, we had an important tool on our side: open bargaining. Throughout the two years of bargaining, we held our negotiation sessions over Zoom, with any union member able to sit in and observe. After members witnessed management’s behaviour at the bargaining table, they no longer needed to be convinced to take action. They saw what was necessary with their own eyes.

Philadelphia Museum of Art educator Adam Rizzo speaks with a reporter during last year's strike Photo by Tim Tiebout

Perhaps management thought that if negotiations dragged on long enough, high turnover would cause us to lose momentum. Instead, every act of stalling and disrespect convinced more and more workers to get involved, whether they had been at the PMA for ten years or two weeks. When we voted to authorise a strike, we did so with 99% of the vote because every member had been given the chance to draw their own conclusions and make an informed decision.

Recognise your power and resources

We timed our strike to align with the installation of the museum’s major fall exhibition, Matisse in the 1930s, knowing that our board of trustees would not want a large loan show—or the fancy opening party, scheduled for 15 October—to be disrupted or delayed. We picketed every day the museum was open to the public, heavily reducing admissions revenue. We leaned on the Philadelphia community, who joined us on the picket line and sustained us with food, coffee and donations to our strike fund. Local artists, labour unions and elected officials all added their voices in support.

A museum going on strike does not disrupt the manufacture of a product or make other industries grind to a halt. But our workplaces are highly visible, have official or informal obligations to the public and cannot be simply shut down and reopened elsewhere. These are all useful factors for creating powerful pressure campaigns.

A union contract is not a silver bullet. Now that we have one, we need to make sure it is put into practice every day. But we walked back into work with a new sense of solidarity and power. When we negotiate our next contract for 2025, perhaps our board of trustees and senior executives will have learned something from this experience. Their workers certainly have.

- Adam Rizzo is an educator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the president of the museum union