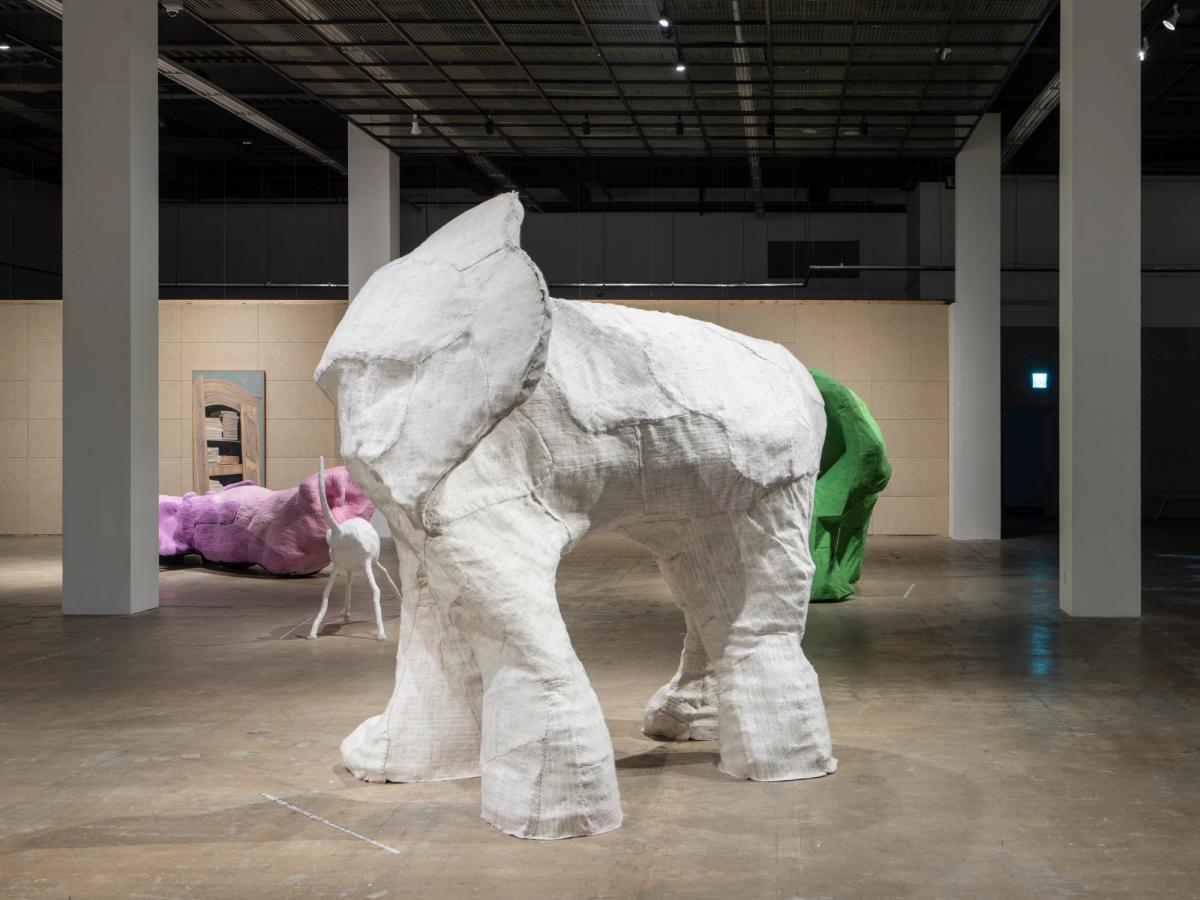

Oum Jeongsoon’s series Elephant Without Trunk (2023), the centrepiece of the first section of the 2023 Gwangju Biennale (until 9 July), defies the question of how to see an elephant. Referencing the parable of three blind men interpreting an elephant by touching a part of it—variously imagining it as a tree, a snake or a rope—Oum depicts in the work how the visually impaired collaborators in her organisation Our Eyes imagine an elephant to be. The soft surfaces of the fabric installation provide a tactile experience as comforting as the visuals could seem deformed and monstrous. Oum posits that the real deformation is in our prioritisation of seeing above all other senses, in the default ableism of art as visual.

“Members of the public were really touching it. There’s a sign saying you can, and that is very unusual. People seem really pleased at the invitation,” says Kerryn Greenberg, who associate-curated the 14th edition of Asia’s fourth-oldest biennial under artistic director Sook-Kyung Lee along with assistant curators Sooyoung Leam and Harry C. H. Choi. “It is real engagement with how we experience the world and art, it is not just visual. The work asks: how do we navigate the world? How do we give a platform to people who have navigated differently than you and I? How do we actually recognise that all of those viewpoints are equally valid and actually have a rightful place? That we all have something to learn from each other?”.

Oum Jeongsoon, Elephant Without Trunk (2023) Photo: glimworkers

These questions underline the biennial's theme: Soft and weak, like water, a characteristic extolled as a virtue by the ancient Chinese philosophical text. “The show doesn’t appear to be about politics, yet many of the works are deeply political—just not overtly,” Greenberg says. The topic “means a sensibility and sensitivity in the work that belies political power. Artists don’t need to be shouting from the rooftops, putting out protest signs. It can be political in a way that is gentle and caring. Politics has failed us to a large degree, which gives us an opportunity to rethink the world and come up with a different set of solutions,” drawing on ancestral, indigenous ideas that are “collaborative and regenerative”.

Disabled perspectives

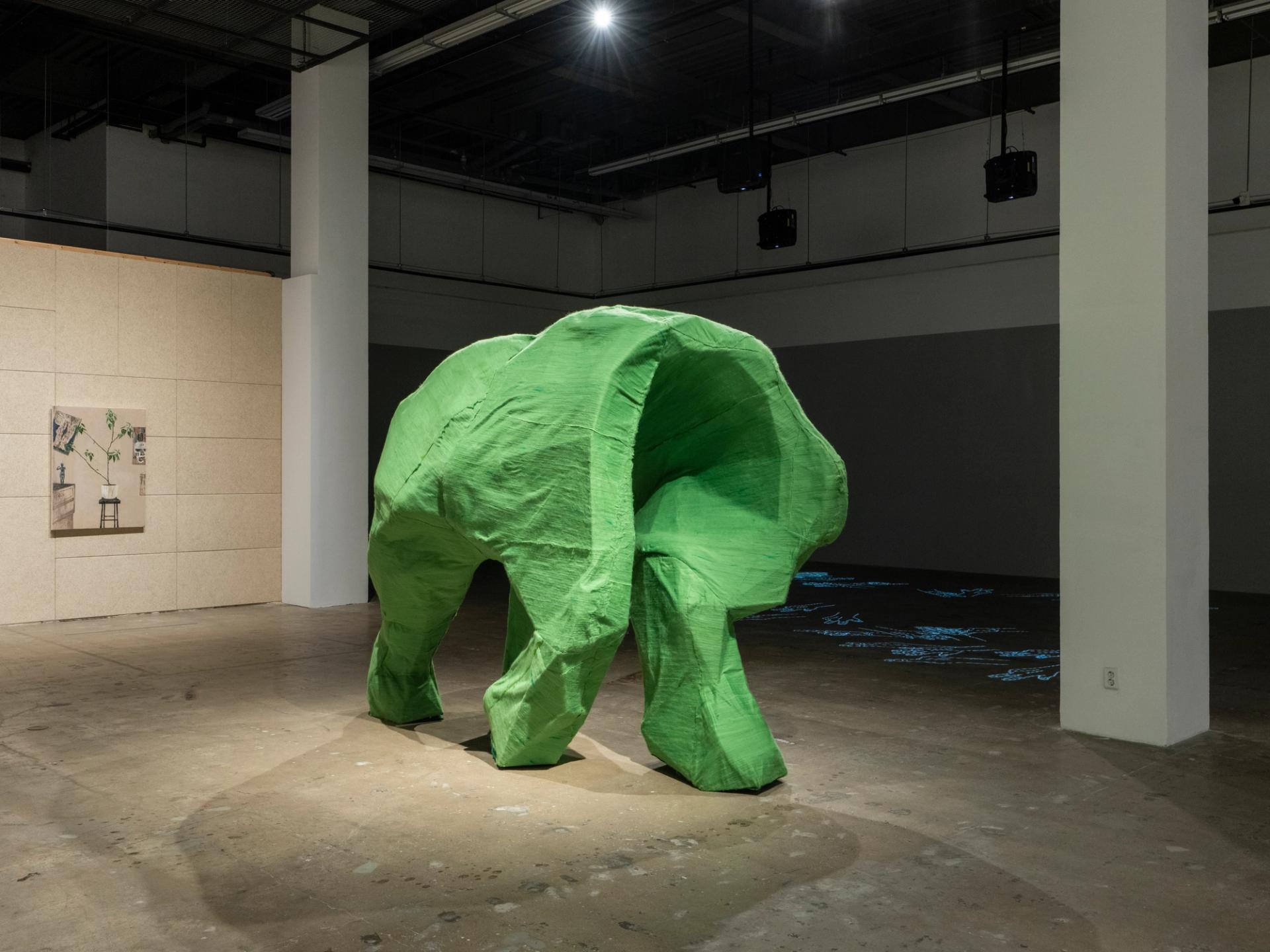

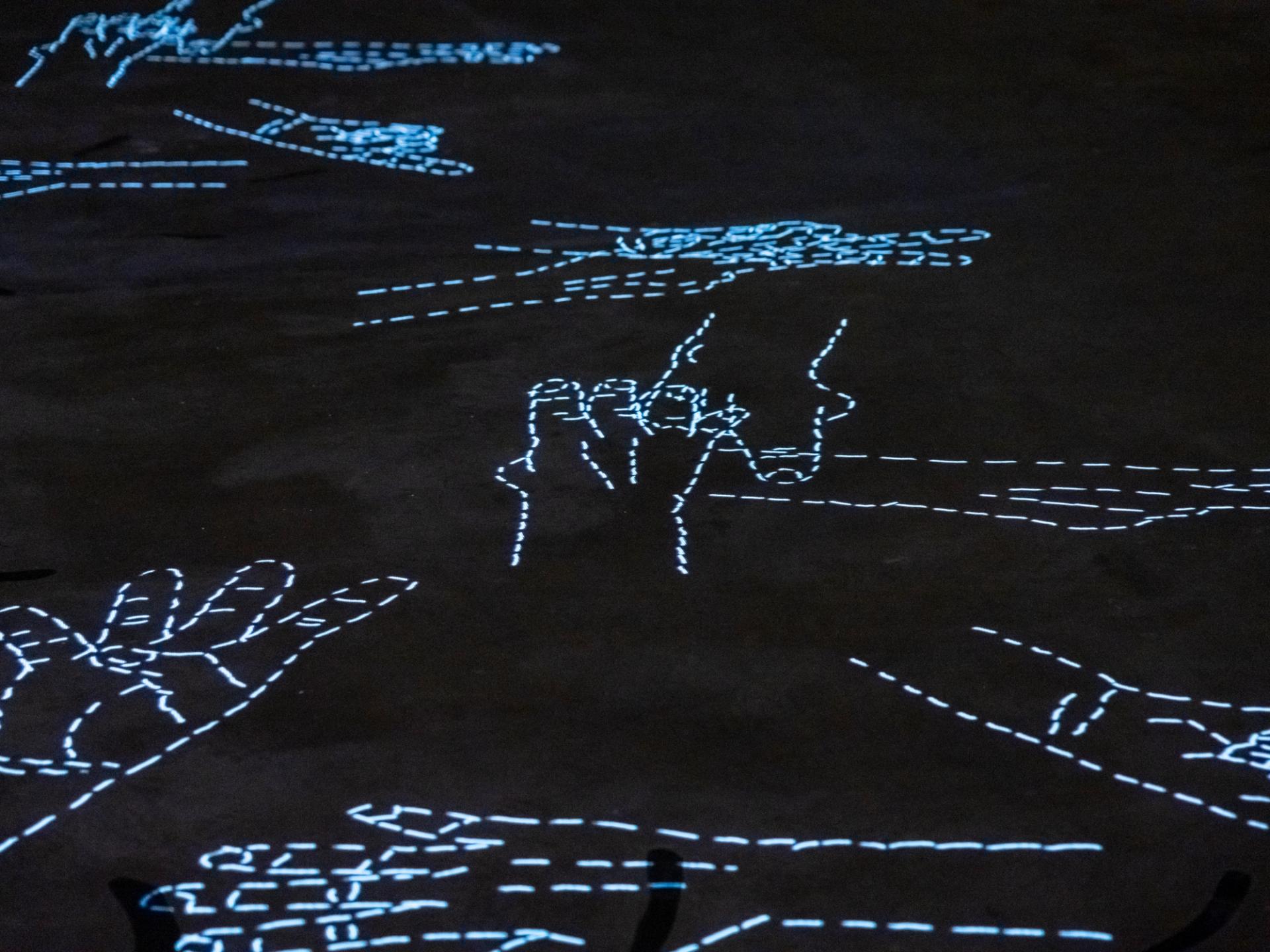

The inaugural winner of the biennial’s Park Seo-Bo Prize, Oum has her work positioned alongside deaf Korean-American artist Christine Sun Kim’s Every Life Signs (2022) installation and video about counting in American Sign Language. The particular space given to disabled perspectives forms part of the opening section Luminous Halo, which centres the biennial’s existential mandate as a living monument to the democratic spirit of the 1980 Gwangju Uprising and Massacre. The 79-artist show then delves into past, present and future with the Ancestral Voices, Transient Sovereignty, and Planetary Times sections, plus a prelude Encounter section with Buhlebezwe Siwani’s immersive The Spirits Descend (2022).

“It is not about a surface touching on the Gwangju spirit, it rather is an aspiration,” says Lee, a senior curator of international art at Tate Modern. “Choosing a biennale as [the tragedy’s] legacy is quite honourable. It comes from how they value art, for hundreds of years. It really is a cultural region, known for music, art, theatre.”

Christine Sun Kim’s Every Life Signs (2022) Photo: glimworkers

Tragedy

The Gwangju Uprising, part of a succession of viciously suppressed uprisings against brutal American-backed anti-communist dictators, was decisive in South Korean history. The 1975 fall of South Vietnam prompted general Park Chung-hee’s closure of universities and banning of 483 “unhealthy” songs. Following Park’s 1979 assassination and a coup that installed Chun Doo-Hwan as dictator, new student protests broke out around South Korea in spring 1980. In Gwangju, phone lines were cut as soldiers began indiscriminately pulling people off buses and out of taxis to detain, beat, torture and bayonet. On 18 May, the small city’s residents united to fight back, with bus and taxi drivers charging their vehicles into the makeshift barracks in a football stadium.

The military fled, and for a week the people of Gwangju enjoyed an unusual degree of self-ruling safety and freedom, comparable to the Paris Commune of 1871. On 27 May, with explicit support from Jimmy Carter’s White House, Chun’s regime sent in 20,000 paratroopers normally posted in the demilitarised zone buffer with North Korea. They slaughtered between a hundred and a thousand people.

An apology

The 2023 Gwangju Biennale opening came shortly after Chun Doo-hwan’s US-based grandson met with Gwangju Massacre survivors to apologise for the carnage and to clean a victim’s grave. Jamie Chun Woo-won had previously denounced his family and confessed struggles with mental health and substance abuse on social media. “This very fragile young person, not even born but knowing his family history of that crime … found a huge affinity with Gwangju people,” Lee says.

Chun Won-woo’s apology has generated mixed reactions in Korea but envy in the Philippines and Taiwan, where the unapologetic son and purported great-grandson of deposed dictators are now, respectively, president and mayor. Along with Gwangju’s local government establishing the biennial and a peace prize in memorial, Korea’s national government apologised for the massacre in 1988, and in 2018 a defence minister apologised for mass rapes during the incident.

“Gwangju has become a clear indicator of where people stand”

“Like everywhere else, Korea is sharply divided between left and right now,” Lee says. “Gwangju has become a clear indicator of where people stand.” Downplaying Gwangju casualties and falsely claiming the uprising was a North Korean plot remain popular in the Korean right.

The Korean first spouse traditionally opens the Gwangju Biennale, but this year first lady Kim Keon-hee was conspicuously absent, replaced by dozens of opposition Democratic Party representatives announced to cheers. The Biennale Foundation itself is recuperating from a 2021 cloud around former director Sunjung Kim, who attempted to restructure and privatise the public foundation and was found guilty by the labour bureau of workplace harassment. “She interfered significantly with areas [beyond those] delegated to the artistic director,” explains a foundation spokesperson.

Expansion

This year the biennial has expanded the satellite national pavilions—organised by entities such as the state National Museum of China and Israel’s independent Center for Digital Art Holon—from five to nine. Current foundation president Park Yang-woo said at the opening that the aim is to expand to 20 countries in 2025. Dusu Choi, chief of the biennial’s exhibition team, says the programme is in an “ongoing experimental stage” largely arranged by “respective embassies or cultural centres in Korea”, a practice the biennale expects to keep flexible.

“To observe and view the spirit of Gwangju from various perspectives, more cultural discourses and stories need to be discussed,” Choi says, even if it involves state entities from autocracies. “Instead of seeking simple harmony, the Gwangju Biennale is preparing to become a site where issues and discourses are generated through joint discussions… The spirit of Gwangju is a concept that is difficult to define in a single way.”