The National Gallery in London will next week display a couple of unusual objects for an art museum. A tattered piece of brown cloth and a rope belt, claimed to be more than 800 years old, will sit among beautiful loans from public and private collections, as well as the museum’s own paintings by the likes of Sassetta and Sandro Botticelli.

The exhibition also comes with a message from the Pope, welcoming the first show in the UK devoted to Francis of Assisi, the saint he describes as “the beloved minstrel of God”. In 2013 Jorge Mario Bergoglio took the saint’s name as his own when he became Pope Francis, and went on to quote the beautiful Canticle of the Sun, in which Francis embraced sun, moon and even Sister Death as family.

He was beaten by his appalled father for abandoning his fine clothes to embrace poverty

The man nicknamed Il Poverello—“the little poor man”—has equally inspired artists: the exhibition will include works across centuries up to Richard Long’s text piece and river mud painting made especially for the exhibition to mark the artist’s walk through the saint’s landscape.

Francisco de Zurbarán's Saint Francis in Meditation (1635-39) © The National Gallery, London

The organisers of the show, the National Gallery director Gabriele Finaldi and the museum’s curator of art and religion Joost Joustra, believe Francis may be the most portrayed and written about of all saints. Unlike early saints tangled in legends and folklore, he was unquestionably a real man, born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone in Assisi in 1181, a cloth merchant’s son beaten by his appalled father for abandoning his fine clothes to embrace poverty. His own writings survive, and a 14th-century copy of some of them, with a little drawing, is coming from Assisi.

Within two years of his death in 1226, he was canonised, the first paintings were made, the first lives written, and the first Franciscan missionaries sent to England. Within a century there were images of Francis in churches across Europe, gaunt in his patched robe or a more endearing figure preaching to birds, or shaking hands with a wolf and ordering it to stop eating the people of Gubbio.

The cycle of Giotto frescoes in the enormous basilica in Assisi is often credited with launching the Italian Renaissance, and Francis’s message of poverty, service and simplicity—swamped in his lifetime by the explosive growth and wealth of the order he founded—has even inspired a 1980 Marvel comic. Finaldi, in his catalogue introduction, describes him as attractive “for Christians and non-Christians alike, for utopians and revolutionaries, for animal lovers and for those who work for causes of human solidarity”.

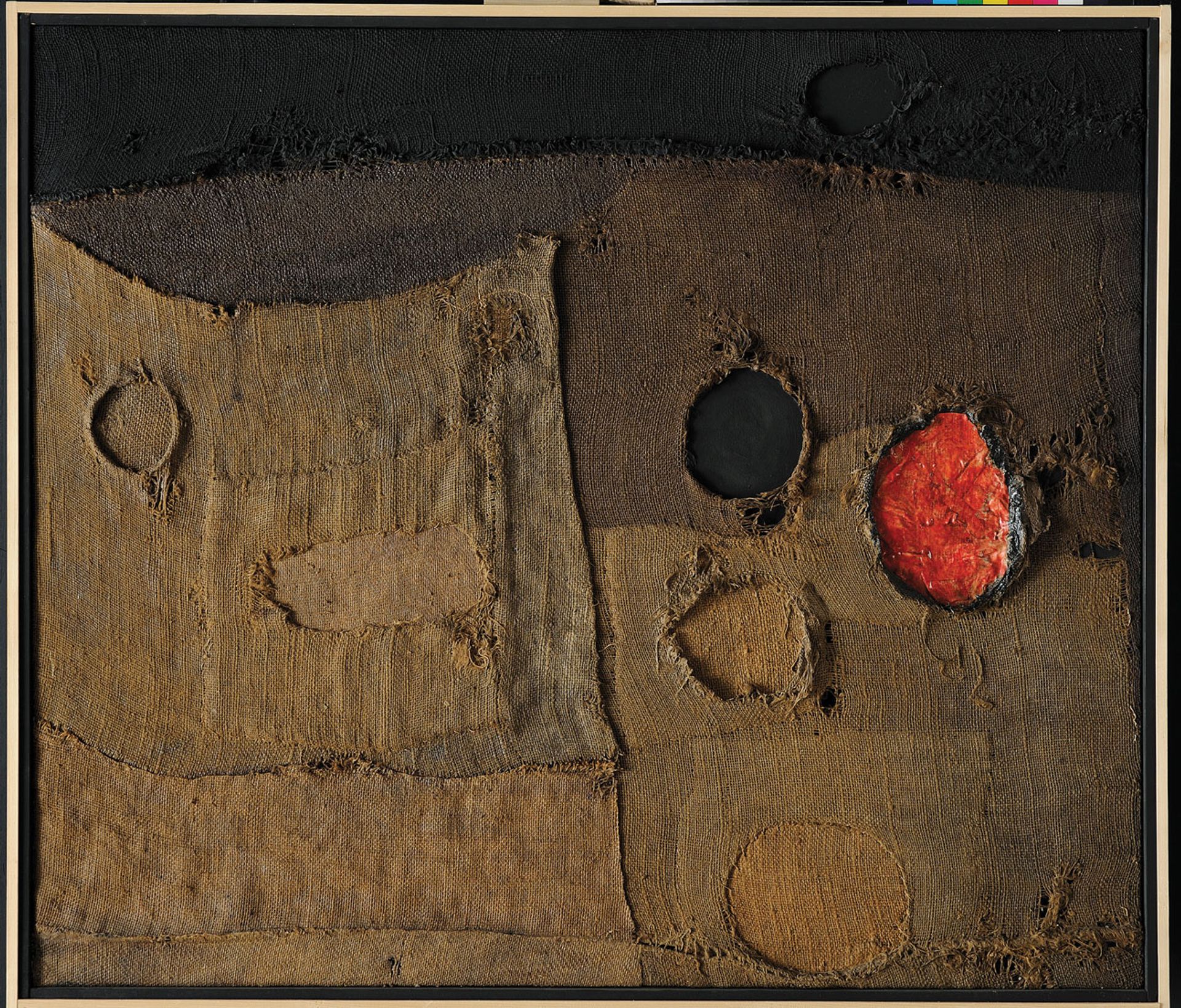

Alberto Burri Sacco (1953) © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello; Photo: Alessandro Sarteanesi

The crudely stitched brown cloth, folded into a golden reliquary from the basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, is one of several believed to have been owned by Francis. These modest relics have inspired many artists and works in the show, including Alberto Burri’s Sacchi (sacks) paintings, which were exhibited in 1975 in Assisi, and Antony Gormley’s life-sized figure made from heavily soldered lead panels, pierced to suggest the stigmata wounds of Christ’s crucifixion.

The very intensity of devotion to Francis has sometimes sparked suspicion. In 1853, when the National Gallery bought Saint Francis in Meditation (1635-39) by Francisco de Zurbarán, one critic described it as “a small black repulsive picture”. In contrast, Stanley Spencer’s St Francis and the Birds, coming from the Tate and showing a stout friar with a flock at his heels, was deemed insufficiently reverent and rejected by the Royal Academy of Arts in 1935.

Stanley Spencer’s St Francis and the Birds (1935) was rejected for the 1935 Royal Academy of Arts summer exhibition for lacking the necessary reverence

© Tate/Tate Images

The exhibition was originally proposed by the curator Minna Moore Ede, who has since left, and was postponed due to the pandemic. The delay, however, allowed time to include a painting that resurfaced in a private US collection after an appeal in The Art Newspaper in April 2021. Saint Francis and the Heavenly Melody (1904) by Frank Cadogan Cowper—dubbed “the last Pre-Raphaelite”—is described by Finaldi as a “quirky, preternaturally clear and very English” view of a saint for all seasons.

• Saint Francis of Assisi, National Gallery, London, 6 May-30 July