The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London began to develop a permanent collection of photography in 1852, the year it was founded. This early recognition of photography was pioneering, marking the V&A out as the first museum to collect photography in the world. Today, the museum holds upwards of 800,000 photographic items. But, for much of its history, the V&A only exhibited tiny fragments of its world-renowned collection of photography to the public.

Not any more. On 25 May, the museum will mark the long-awaited completion of the Photography Centre. “The momentum behind photography at the V&A is bigger now than ever before,” says Marta Weiss, a senior curator of photography at the V&A.

Phase one

The centre, which is situated in the north-east wing of the museum in South Kensington, has had a long gestation period. Phase one of the project opened in 2018, attracting three times as many visitors as expected. “It was our first proper attempt to claim a space within the museum,” says Martin Barnes, a senior curator of photographs who runs the V&A’s photography department.

A rendering of the Parasol Foundation Gallery (room 97) in the V&A’s Photography Centre, which was funded by a donation from Ruth Monicka Parasol, who made her fortune selling adult entertainment

© Gibson Thornley Architects

But phase one comprised just three galleries. Now, a second and final phase has added four more. Combined, the centre’s seven galleries now total more than 1,000 sq. m of exhibition space along the full length of the museum’s north-east quarter.

“We wanted to show photography in all of the ways it exists, from the book page to the glass negative to the print on a wall to the digital,” Barnes says. “We are one of the few places in the world you can come to and reliably be able to see that range.”

The Photography Centre gathered pace when the photography department’s already expansive holdings were bolstered by the addition, in 2016, of the Royal Photographic Society’s archive of photographs, books and cameras. The collection was formerly held at the National Science and Media Museum in the Yorkshire city of Bradford.

Endowment

But the collection is not inert. It is a living, evolving and ever-changing thing—one driven by a dynamic contemporary acquisitions programme. In September 2021, the V&A announced the Parasol Women in Photography Project, made possible via a £3m endowment from the Parasol Foundation Trust. The funding comes from Ruth Monicka Parasol, a billionaire philanthropist from San Francisco, who, somewhat ironically, made her fortune in part by selling adult entertainment.

In March 2022, the V&A appointed Fiona Rogers, the former chief operating officer of Magnum, the prestigious photography co-operative, as the Parasol Foundation curator of women in photography, a newly created post. Her appointment reflected the need to “rebalance” the collection, she says. Only 15% of the existing collection is by women, a statistic Rogers is keen to change.

“We are in the process of mapping the existing collection,” Rogers says.

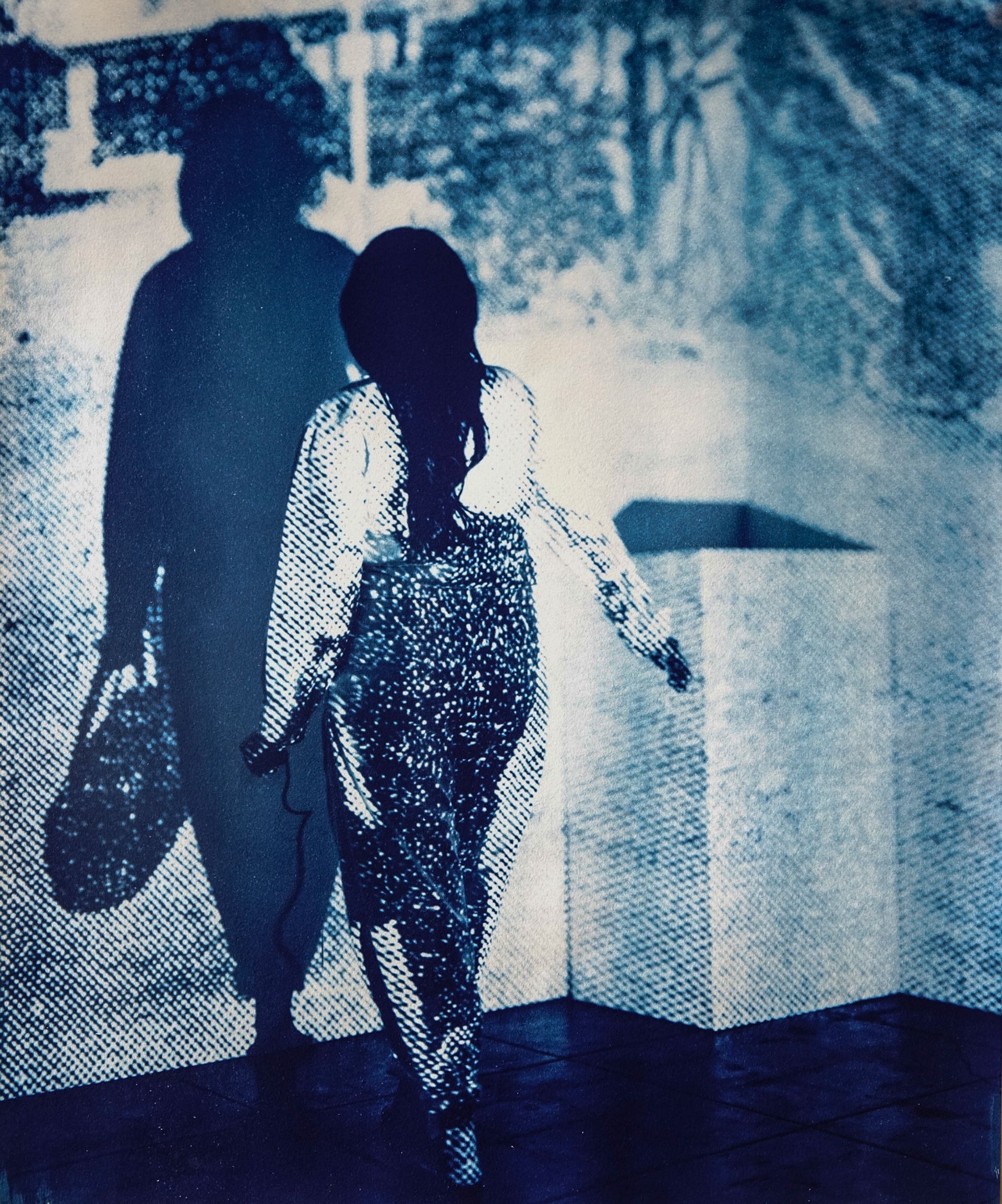

Tarrah Krajnak's Self Portrait as Walking Woman with Bag, 1979 Lima, Peru 2019 Los Angeles, CA, from the series 1979 Contact Negatives (2019–22) © Tarrah Krajnak

Alternative histories

Rogers’s work is reflected in the centre’s inaugural exhibition, which will feature—alongside ephemera dating back to the birth of the medium—new creations by the contemporary British photographer Liz Johnson Artur and the German artist Vera Lutter, as well as a Parasol Foundation Trust-funded series of contemporary self-portraits by the Peruvian photographer Tarrah Krajnak. “We are trying to be strategic in our acquisition and programming activities,” Rogers says.

“We’ve searched for underrepresented communities and overlooked stories, primarily by women artists”Fiona Rogers, the V&A's Parasol Foundation curator of women in photography

As well as championing new artists, Rogers and her team have mined the collection, searching for photography that might have been ignored by generations but sheds light on alternative histories. On social media, Rogers has revisited the photography of Julia Margaret Cameron, who was given her first show at the then South Kensington Museum in 1865. But she is also sharing the contents of hand-adorned photography albums created by unknown women from the Victorian era, as well as sharing Isabel Agnes Cowper’s 19th-century documentation of the V&A’s objects and spaces in her capacity as the first female official museum photographer of the South Kensington Museum, as the V&A was known from its official opening in 1857 to 1899. “We’ve searched for underrepresented communities and overlooked stories, primarily by women artists,” Rogers says.

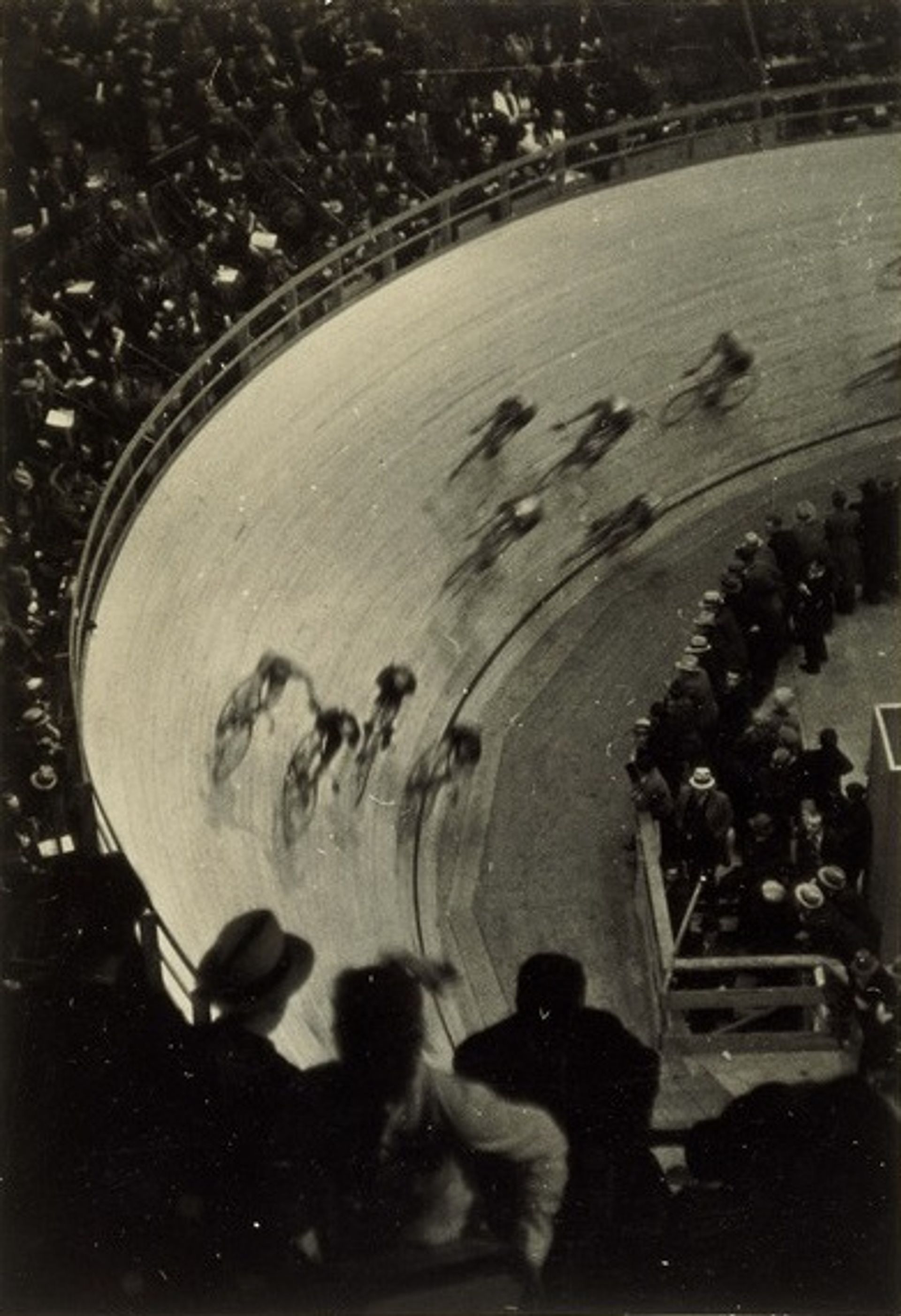

Fred Zinnemann's Madison Square Garden, Velodrome (1932) Museum no. E.1683-1989 © The Estate of Fred Zinnemann Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery

Inner space

Most institutions would build something entirely new to house this kind of venture. The V&A, by contrast, has pursued a principle of inward expansion, aiming to return the building to its original 19th-century glories while also making it accessible to a 21st-century audience.

The Photography Centre is comprised of new galleries that, for decades, were back-of-house rooms. Before the restoration, rooms 96, 97 and 98 were variously used as student classrooms and storage rooms for the museum’s textiles. But the restoration has revealed the secrets of the V&A’s history. Vaulted ceilings and archways with original timber panelling covered in hessian were uncovered and refurbished. Room 95 was a cleaner’s cupboard, which, for much of the building’s 166-year history, has never been made accessible to the public. It will now play host to a walk-in camera obscura.