At Lismore Castle, the Irish home of the Dukes of Devonshire, the eyes of history are always upon you. Built by King John in the 12th century and for a while owned by the Elizabethan buccaneer-coloniser Walter Raleigh, it perches like a turreted fairytale confection above the River Blackwater in County Waterford. In the 19th century, it received a full Victorian Gothic makeover from the architects Joseph Paxton and A.W.N. Pugin, the latter of whom is best known for his ornate interiors of the Palace of Westminster in London.

In 1932 Lismore got a further upgrade when it was given as a wedding present by the ninth duke to his younger son Charles Cavendish upon his marriage to Adèle Astaire, the sibling and dancing partner of Fred. Astaire stumped up for her creature comforts: as a contemporary wag observed, the castle was built by King John and plumbed by Adèle Astaire.

Lismore Castle in County Waterford, the Irish home of the Dukes of Devonshire

Such weight of heritage makes Lismore a compelling but also formidable context for contemporary art. Since 2005 the current heir William Cavendish and his wife Laura have invited a multifarious roster of artists ranging from Matthew Barney and Rashid Johnson to Richard Long, Eddie Peake and Superflex to take part in the Lismore Castle Arts programme, in guest curated shows, solo representations or special commissions. In some cases the work has been directly influenced by the surroundings, as in The Heir and Astaire (2010), T.J. Wilcox’s short film about Lismore’s jazz-age merger of aristocracy with showbiz, while others have chimed more obliquely with Lismore, such as Sean Lynch’s group show Reverse!Pugin, which took the castle’s ornamental design as a starting point to investigate human use and abuse of the landscape, both for art and for profit, in Ireland and beyond.

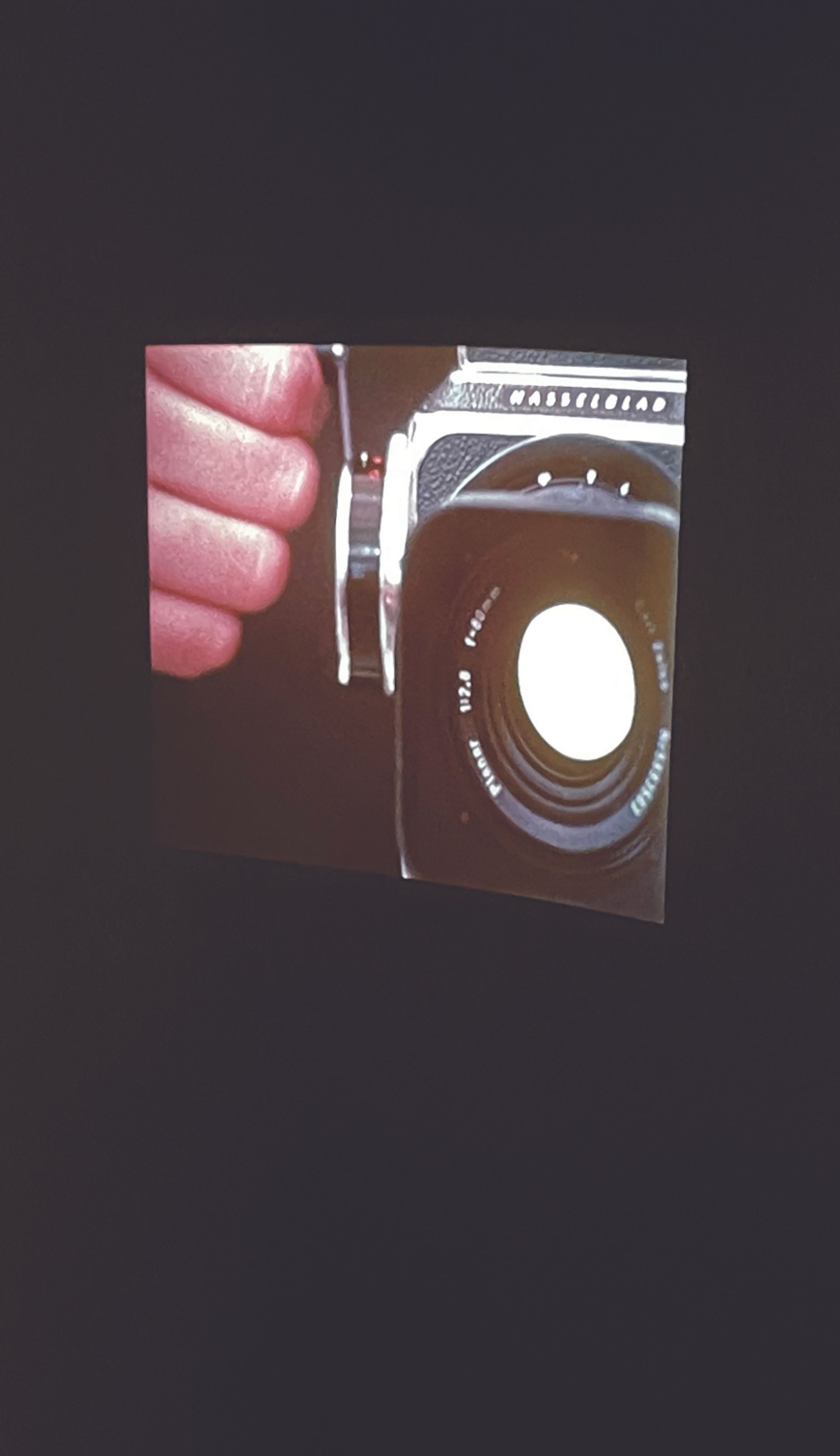

Anne Collier's Shutter (2022)

All works courtesy of the artist; The Modern Institute/ Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow; Anton Kern Gallery, New York; Galerie Neu, Berlin; and Gladstone Gallery, Brussels

Anne Collier, who is currently showing in the castle’s converted west wing galleries, has not made work especially for Lismore. But this doesn’t prevent her exhibition Eye from resonating powerfully with its context. California-born, New York-based Collier has always had a particular interest in exploring the ways in which the act of looking or being looked at is embedded within the photographic process, while also examining the ambivalent role of the camera as an instrument of both emancipation and subjugation.

Deadpan representation

As per its title, Eye is dominated by images of female eyes sourced from comics, film stills, advertisements and photography manuals, as well as shots of the artist’s own eye. Clichés, tropes, assumptions and stereotypes swirl around Collier’s deadpan representations of these women, many of whom are depicted as weeping and distraught. The cool, objective way in which these images of emotional in extremis have been reframed only heightens their fraught and often problematic subject/object nature.

Collier also subjects herself to scrutiny with a trio of works where black-and-white photographs of her own eye appear variously in a developing tray, being held aloft by a disembodied arm and, most disconcertingly, in the process of being slashed with a paper cutter—reminiscent of the excruciating eyeball razor scene in Luis Buñuel’s classic 1929 film Un Chien Andalou.

Installation view of Ann Collier: Eye at Lismore Castle Arts

Collier wears her art historical, feminist and theoretical references lightly, but the proximity of these complex, discursive works to the abundance of family portraits that gaze down from the walls of Lismore—including some glamorous photographs of Astaire in her role as Lady Charles—undoubtedly gives them an extra edge. Togged up to the max to display their wealth and privilege, many of Lismore’s lavishly portrayed duchesses and lady wives were nonetheless largely powerless instruments in the securement of dynastic bloodlines and/or the forging of lucrative family alliances.

It is impossible not to see correspondences between the mixed messages embedded in these historic images of the ladies of Lismore and Collier’s sardonic eyeballing of more modern but no less reductive female sexual and emotional archetypes. I’m sure that Eye would also have chimed with Astaire, who had more than her share of grief but was by no means a victim. After ceasing to be the chatelaine of Lismore, she struck a deal with the Devonshires to return to the castle every summer, which she regularly did for the next three decades, even after she had remarried and was living between New York, Phoenix and Jamaica. The swimming pool that she created may now have been filled in, but the plumbing still works a treat.

• Anne Collier: Eye, Lismore Castle Arts, 25 March-29 October