In circles both artistic and environmental, the very mention of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) often causes lips to curl. These digital units, which use blockchain technology to record the ownership of an artwork (or any other asset), are widely decried as vehicles for financial speculation with little intrinsic artistic value. Then there’s the environmental impact. NFTs are criticised for their heavy carbon footprint, residing as they do on the notoriously power-intensive blockchain and requiring huge amounts of energy to be minted. A 2021 analysis of around 18,000 NFTs by the digital artist Memo Akten found that the average footprint of a single NFT was equivalent to a month’s electricity usage by an average EU resident.

But now the tide seems to be turning. Many of the biggest NFT marketplaces operate on the Ethereum blockchain, which cut carbon emissions by more than 99% in an upgrade known as “the Merge” in September 2022. The network switched to a different “proof of stake” system that requires only a fraction of energy per transaction compared to the previous “proof of work” system. Other blockchains such as Tezos, Cardano and Kusama also use the “proof of stake” mechanism which looks like it is becoming the norm for minting and trading more energy-efficient NFTs.

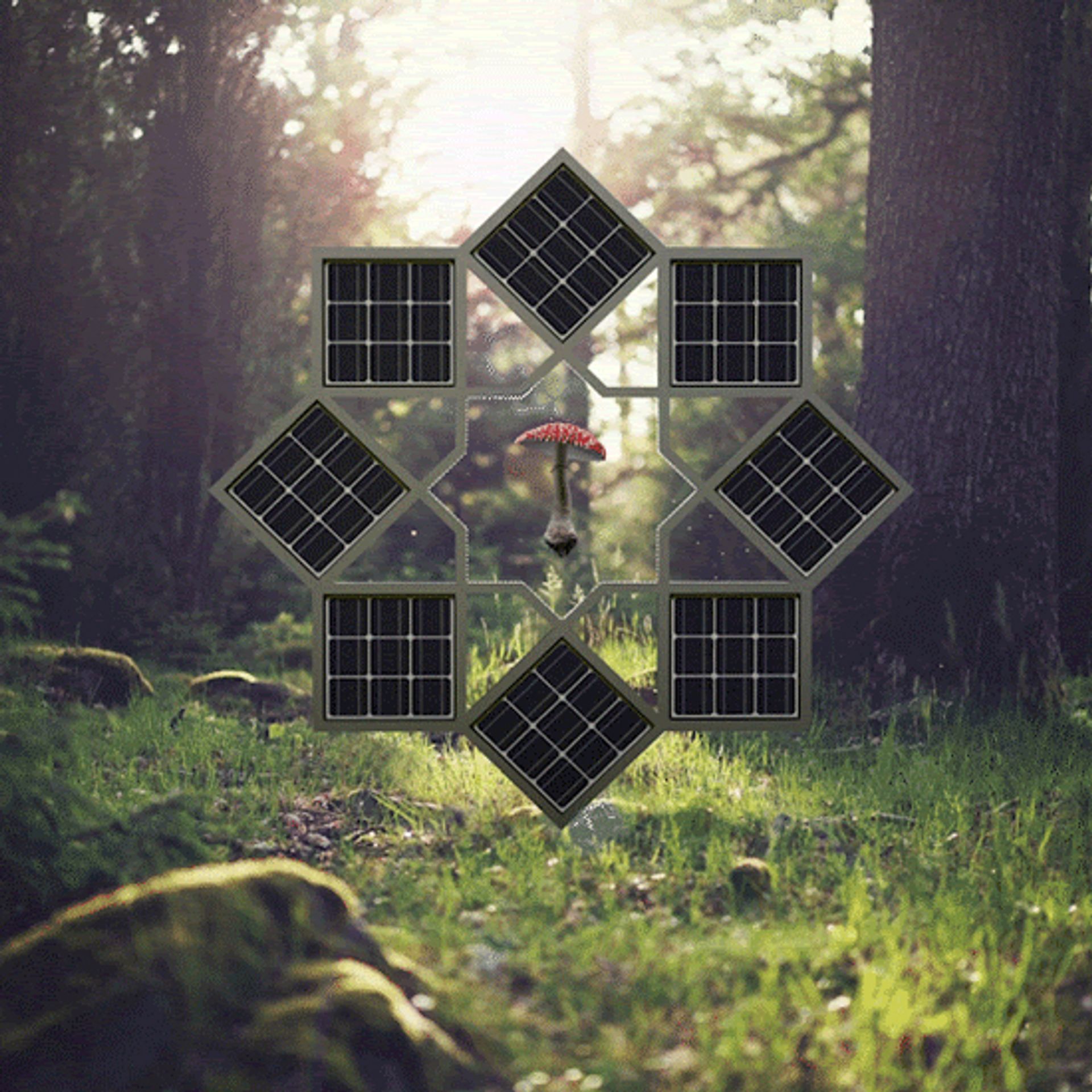

Still of Haroon Mirza's Solstice Star NFT

Courtesy of the artist and Lisson gallery

What’s more, the crypto crash last year has reduced the hype surrounding NFTs and artists are starting to feel less squeamish about exploring the potential of blockchain as a creative space. Case in point is Haroon Mirza, an artist who works with sound, light and electricity to create kinetic sculptures, performances and immersive installations, who launched his first NFT project during his recent show at London’s Lisson Gallery. Solstice Star released the first 200 of 1,000 minted NFTs—featuring a GIF of a red-and-white fly agaric mushroom framed by a star of eight rotating solar panels—for free to anyone logging on to solsticestar.xyz and verse.works.

“I was immediately into cryptocurrencies and I’ve always thought that blockchain was an incredible technology that’s going to revolutionise how we do things,” Mirza says. But while intrigued by the initial emergence of NFTs, he was quickly put off by the feeding frenzy around the $69m Beeple sale at Christie’s in March 2021. “It became like a Ponzi scheme within a Ponzi scheme and I didn’t want anything to do with that part of it,” he states. “It just became a way to invest in often dirty crypto and the type of art that went with it just made you want to throw up.”

The subsidence of speculative interest in NFTs along with the switch to a more sustainable system encouraged Mirza—whose work often revolves around the technological pursuit of energy—to revisit the blockchain. “The Merge has made Ethereum a completely different platform to what it was before,” he says, adding that for him the appeal of NFTs is conceptual rather than aesthetic.

“Nothing about the NFT interests me other than the fact that the artwork is also the certificate and completely transparent, with everything inherent in the work itself,” he states. “NFTs are completely decentralised—I like the idea of an artwork being a non-hierarchical community that can engage with itself in a productive way. It’s like having an artwork that is inherently collaborative: it’s what I do in my work anyway, and that’s the thing that really excites me.”

For Mirza, Solstice Star is simply “a first step, an entry point” into a larger interactive project that will unfold over time. The next iteration will incorporate sound, a key part of his practice. All the owners of Solstice Star NFTs will be invited to select a frequency within the human hearing range of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz, which will then be used by the artist to create a new sound work.

“The potential is that you can evolve a project that has a feedback loop with the people that are collecting it,” the artist says. “It’s a living thing, a live project that can grow and develop into a non-hierarchical network.” Down the line, the project also promises to reap environmental benefits, with Mirza aiming to put in place a smart contract that will direct some of the proceeds towards research into renewable energies.

The communal, participatory aspect of NFTs is also a major draw for Mat Collishaw who, like Mirza, is making his first foray into the field. “I’m always looking for new media and if there is a new form for making an artwork, with a new vocabulary attached to it, then I want to be in there,” says Collishaw. In the past the artist has used VR, animatronics and CGI as well as oil paint, mosaic, and blown glass to make stunning and sometimes shocking artworks that explore ideas around death, decay and the darker side of human nature.

The "greenhouse", part of Mat Collishaw's Heterosis NFT project

Courtesy of the artist

Drawing parallels between the craze for NFTs and 17th-century “tulip mania”, when entire fortunes were made and lost speculating on tulip bulbs in the Netherlands, Collishaw created Heterosis, an NFT project which allows users to cultivate bespoke animated digital flowers. Each one of these unique NFT blooms combines computer algorithms with floral genetic coding, thus enabling collectors to collaborate with one another on new hybrid species. The result is an infinite range of ever more exotic and elaborate creations. Collectors can manipulate their specimens just for pleasure or for the financial rewards of reselling them—or both.

“It’s absolutely down to the collectors what they do,” Collishaw says. “The first iteration of the flower is fairly simple and the colours are pretty straightforward. They can get a lot more elaborate… we wanted to give people the incentive to breed.” To spice things up, the artist has introduced a number of recessive genes that will throw up new characteristics impossible to control or predict. “There are several secret species that will be unlocked when certain breeding patterns are done,” he declares. How these surprise features will affect a flower’s resale value remains to be seen.

Since they were released on the OpenSea NFT platform last month, all 2,500 of these infinitely mutate-able blooms have been snapped up at the initial cost of around £120 each in cryptocurrency. Collishaw is pleased that collectors have already begun to interact with each other to hybridise their flowers. Apparently some are even making additional revenue by setting competitive prices for anyone wanting to breed from theirs. The more sought-after the individual flower, the higher the price.

The "greenhouse", part of Mat Collishaw's Heterosis NFT project

Courtesy of the artist

These hybridising transactions take place in a centralised digital space called “the Greenhouse” where collectors can adopt an avatar, contact other participants and view all the Heterosis flowers growing in their most recent state. Here all the properties of a specimen can be assessed, including its market value. In keeping with Collishaw’s track record of finding beauty in entropy, this interactive environment simulates the form of London’s National Gallery if it were abandoned to decay. The flowers are set against a backdrop of mildewed Old Master paintings, while vegetation sprouts from the floor and the ceilings play host to a mass of dangling vines.

Viewing this ghostly setting where the great works of art history are reclaimed by nature, and where nature also co-exists with manipulated digital blooms, raises all manner of questions around value, beauty, desirability, natural and artificial selection. “It’s quite shocking to me that you’ve got the cream of 400 years of European art but nobody is looking because the only organic life is plant life,” the artist observes.

Collishaw also draws analogies between the traditional role of the National Gallery as a networking hub “where citizens could gather and share intelligence” and the circulation of knowledge around natural science, art and commerce exchanged amongst the tulip merchants and speculators in 17th-century Holland. These ideas around informational networks come full circle with the way in which Heterosis encourages its collectors to form an online community to trade data pertaining to their holdings as they bring the project to its full fruition.

Given the botanical theme of the project and its multifaceted exploration of how humankind has shaped the natural world for financial gain, it was especially important for Collishaw to wait for the “proof of stake” blockchain system to be in place before any NFT drop. “I was keeping a close eye on the situation,” he confirms, adding that he is also glad that the intrinsic immateriality of NFTs avoids the shipping, storage and other energy-hungry requirements of analogue art.

The fact that minting NFTs is no longer an environmental hazard has enabled both Collishaw and Mirza, in their very distinct but also overlapping ways, to demonstrate the rich and inclusive potential of the non-fungible token as an interactive artistic endeavour. Never mind that neither artist has yet made much money from their sortie into NFTs—profits were never the point.

As Collishaw puts it, “In making an NFT I created an artwork that exists in a way not possible in any other context. Its value has been as an experiment, and a very interesting one. I’ve learnt a lot doing it—but I could have earned more by cleaning windows.”

However things play out in the crypto market, it looks as if NFT art is very much here to stay in its new, greener form.

• Mat Collishaw: Heterosis

• Mat Collishaw will have a solo exhibition, All Things Fall, at the Bomb Factory Art Foundation, London, 20 April-21 May