In the summer of 1937, some Surrealists vacationed together in the south of France. Their holiday photos have since become art history. Lee Miller and Roland Penrose were there and so were Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso, the Éluards, and Man Ray and Guadeloupean dancer and model Adrienne Fidelin. Fidelin was a regular fixture in this circle for years, though hardly mentioned in written accounts of the Surrealists.

One person who gave her more than a passing mention was British artist Eileen Agar (also part of this vacation crew). Among other things, Agar’s autobiography recounts that when Fidelin met Picasso for the first time she “went up to him, flung her arms around his neck and said, ‘I hear you are quite a good painter’”. What Agar didn’t write, and maybe didn’t know, was that Picasso produced a portrait of Fidelin that summer.

He wasn’t the only one fascinated with the vivacious Fidelin. The same year, Fidelin entranced Harper’s Bazaar readers in likely the first time a Black model appeared in a major American fashion magazine. She also appeared in over 400 photographs by her lover of five years, Man Ray, and photos by Penrose, Miller, Agar and Wols. So as Wendy Grossman, a Man Ray scholar researching Fidelin, perused snapshots from the summer of 1937, it occurred to her there might be another kind of memento. “I just kept saying, there has to be a Picasso painting, or drawing or something of her,” says Grossman, mindful that Picasso painted everyone else in that group.

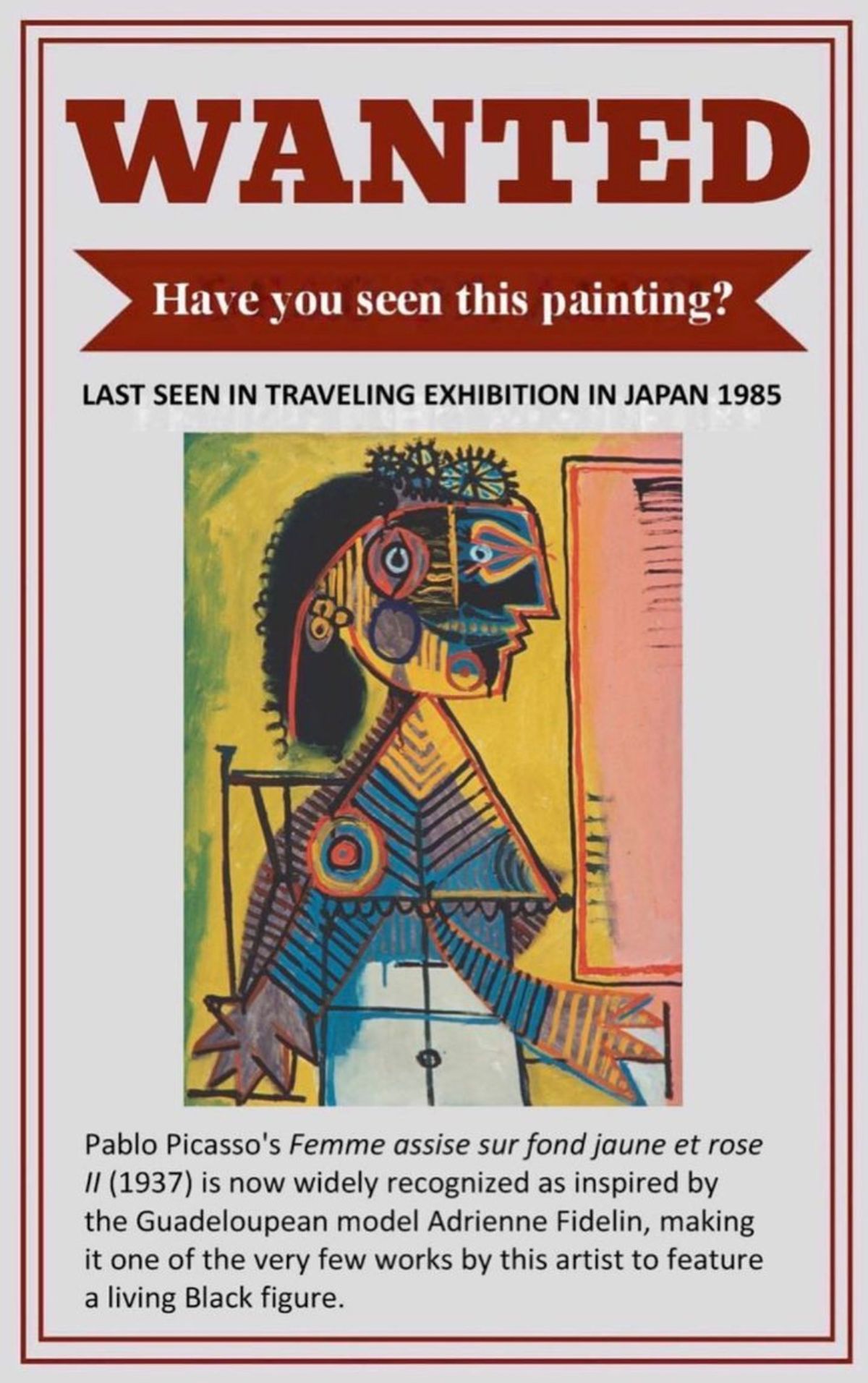

She thought it would be like finding a needle in a haystack, but it was easy because Picasso recorded the dates of his works (not just their year). She looked around summer 1937 and when she saw Femme Assise sur Fond Jaune et Rose, II (1937), she knew she’d found Fidelin because a certain Man Ray photograph was almost identical. In it, a nude Fidelin stands against a wall, holding a ridged washboard.

“Visual characteristics make it clear that this is a woman of colour—her hair texture, the black face,” Grossman says. “But there are two or three coups that completely did it.” Picasso kept Femme Assise in his personal collection until his death, along with two vintage prints of the Man Ray photograph Grossman believes inspired it. Another print of the photograph, in an old auction record, was signed by Man Ray and inscribed “arr Picasso”. “Man Ray’s saying that there’s a relationship with Picasso,” Grossman says.

She had found Fidelin on canvas, only to discover that no one knew where the painting was. The recently deceased Maya Picasso (daughter of Picasso and Marie-Thérèse Walter) inherited it and last showed it in a 1985 traveling exhibition of her collection in Japan. Now a social media campaign led by Grossman and media professional Marie Emedi, dubbed “Finding Ady”, is looking for it in the hopes of exhibiting it and returning Fidelin’s story to mainstream art history.

“It’s bigger than just finding a missing Picasso painting,” Emedi says. “I’m sure that the person who has it knows it’s a Picasso, but I’m hoping that with the more exposure it’s getting, they realize how important what they’re sitting on is.”

Finding Ady launched in early January and has been promoted by figures such as director Spike Lee, who became interested in Fidelin after The New York Times published a belated obituary for her last year. As the campaign continues, they have seen growing interest but no leads yet.

“The search for the missing Picasso painting is the story of the search for Ady,” Grossman says. “The painting’s disappearance or lack of recognition, the fact that nobody ever acknowledged who it was and it was so out of circulation and out of conversation, is similar to how Ady herself disappeared.”