According to the canonical New Testament gospels, Mary Magdalene was a follower of Jesus who supported his ministry from her own means, was witness to his crucifixion and the first witness to his resurrection, and later tasked as apostle to the apostles. Over subsequent centuries, however, her story was retold and her character reimagined. By the medieval period, her conflation with an unnamed sexual sinner saw her popularly reframed as a “prostitute”, and piously repurposed as a model of repentance. In popular culture, her persona continues to be adapted and adopted for creative purposes, as a romantic aside in the otherwise chaste biography of Jesus provided by the New Testament.

It is no surprise, then, that the Magdalene, as she is known, has been a source of enduring fascination for artists, historians and theologians—but we might be forgiven for wondering what more there is to say. Nevertheless, although it would be a stretch to suggest that interest ever truly died, it is undeniable that the elusive biblical everywoman is once more experiencing a scholarly revival.

These recent publications by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, the professor emerita of religious art and cultural history and director of the Catholic Studies programme at Georgetown University, and Philip C. Almond, the professor emeritus in the history of religious thought at the University of Queensland, invite a broader audience to ride the crest of this latest scholarly wave.

Academic but not austere

Apostolos-Cappadona brings her scholarly and pedagogical pedigree to Mary Magdalene: A Visual History, producing a work that is utterly accessible yet richly rewarding for more experienced audiences. The book is shaped by its roots in her 2002 exhibition catalogue In Search of Mary Magdalene: Images and Traditions (American Bible Society), with seven essays in part one that cover written sources, Christian traditions and creative expressions, followed by ten short reflections in part two. The essays are academic but not austere, offering concise précis of key material needed to understand the developing Magdalene iconography.

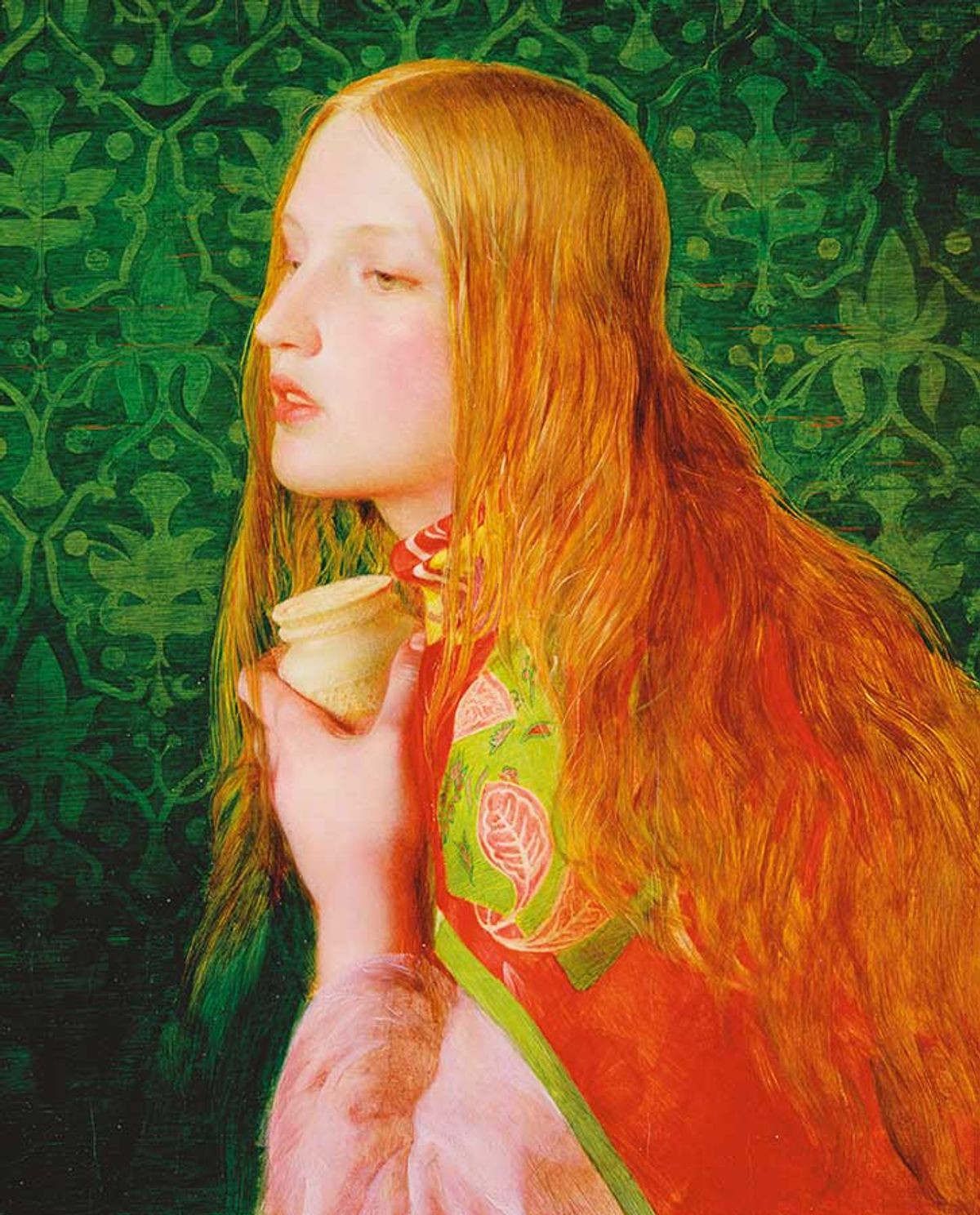

With 65 colour plates, this book is a feast for the eyes, but its readability is the real triumph. “Part One: Toward a Visual History” covers vast ground, but the complexities of biblical sources, early theological sources and the narratives and traditions of Eastern and Western Christianity are recounted with a compelling clarity. The only disappointment in this impressive volume is that the excellent discussion of feminist readings and the significance of the Magdalene’s body is so brief, confined to a three-page coda.

The three-page format becomes the norm in “Part Two: Motifs”, a series of impactful reflections on diverse artistic tropes: sinner/seductress, penitent, anointer, weeper, witness, preacher, contemplative, reader. The longer final reflection on the motif of “Feminist Icon” resumes the discussion from the coda of part one more substantively. Though all of the sections in part two could be given a lengthier treatment, the format works for this volume, whetting the appetite of the reader and affording the art a significant communicative role.

A Visual History opens with an anecdotal preface (including mention of The Art Newspaper) that equips the reader to understand why the work that follows is a labour of love for Apostolos-Cappadona; in the acknowledgements, she describes her interest in the Magdalene as “a lifelong occupation”. A personal and personable narrative voice is maintained across the volume, privileging the reader with the impression of their own private tour across time and place with the expert author as guide.

Three themes upon which this intellectual excursion is apparently centred—“metanoia, unction and metamorphosis”, which we might otherwise recognise as the penitence, anointing and conversion that pervade the Magdalene story—are revisited variously, though never so explicitly as in this preamble. Yet the afterword, ostensibly a reflection on recent Magdalene exhibitions, reveals Apostolos-Cappadona to be setting up others to take the baton. In her words, the book is “an initiation into [Magdalene] iconography and cultural history but hopefully raises for readers new questions leading to the many avenues in Magdalene studies yet to be written ‘in memory of her’”.

Almond’s Mary Magdalene: A Cultural History pursues a quite different approach, surveying the Magdalene’s reception in the Western European tradition. The flap copy, claiming that it is “the first major work on the Magdalene in more than 30 years”, offers a degree of publishing bluster, but the timescale inferred is highly indicative of its intellectual heritage. Those who recognise this indirect reference to Susan Haskins’s 1993 work, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor (HarperCollins), can immediately attain a clear sense of the scope and scale of Almond’s project. Despite the acknowledging of Haskins’s work at the outset, references in the footnotes are surprisingly sparse (especially given that the volume concludes with an epilogue on myth), but perhaps this is indicative of just how much Magdalene scholarship Almond has drawn upon.

A model of repentance: Donatello’s Penitent Magdalene (around 1453-55) shows her isolated in the wilderness

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence © George M. Groutas

Cultural reception

Like Haskins’s Myth and Metaphor, A Cultural History establishes a narrative thread through centuries of cultural reception of the biblical figure, and covers an impressive range of material. The first two chapters deal with biblical and other contemporaneous texts and the complexities of medieval accounts of the Magdalene’s life. An unadorned but uncynical account of the various relic traditions between the fifth century and the Protestant Reformation follows. The latter three chapters adhere to the chronological structure, though their broadening scope means they benefit from the more thematic approach that has been applied.

In “Mary Divided: Sacred and Profane”, the Magdalene’s embroilment in ecclesial acrimony is framed well in its broader Early Modern context. Likewise, “Many Magdalenes: Redeemed and Redeeming” offers a concise overview of the Magdalene archetype in 19th-century discussions of women’s roles and morality. The last chapter, addressing contemporary concerns from The Da Vinci Code to The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, is arguably the trickiest for the reader to navigate, though Almond does an admirable job of ploughing a path through these ever-expanding wilds.

The 29 colour plates that open this volume might falsely raise expectations that A Cultural History will explore artistic traditions more fully, and it is difficult to make the case that this is a comprehensive cultural history without a more substantive engagement with the visual. Presenting this work as a type of biography (like Almond’s other recent publications, including The Antichrist: A New Biography, 2020, also for Cambridge University Press) would have avoided the distraction of a sense of opportunities missed. Luckily, the coincident publication of Apostolos-Cappadona’s A Visual History means that readers need not worry.

For two self-described histories, A Visual History and A Cultural History are particularly forward looking. Both offer fresh treatments of a long-established subject, and both illuminate the potential for a reinvigoration of the study of Magdalene reception. Though not intended as such, these books are ideal companion texts, serving as engaging primers for anyone with an interest in how the story of the Magdalene has been told. Almond provides the most accessible summary to date of the scholarly story so far, and Apostolos-Cappadona’s engaging and intelligent appraisal of artistic interpretation reminds the reader that the Magdalene is a subject that matters still.

• Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, Mary Magdalene: A Visual History, T&T Clark/Bloomsbury, 176pp, 65 colour illustrations, £17.99 (hb), published 23 February 2023

• Philip C. Almond, Mary Magdalene: A Cultural History, Cambridge University Press, 350pp, 29 colour illustrations, £30 (hb), published 1 December 2022

• Siobhán Jolley is a specialist in the portrayal of Mary Magdalene. She is a research fellow in art and religion at the National Gallery, London, a visiting lecturer in religions and theology at King’s College London, and an honorary research fellow at the Centre for Biblical Studies, University of Manchester