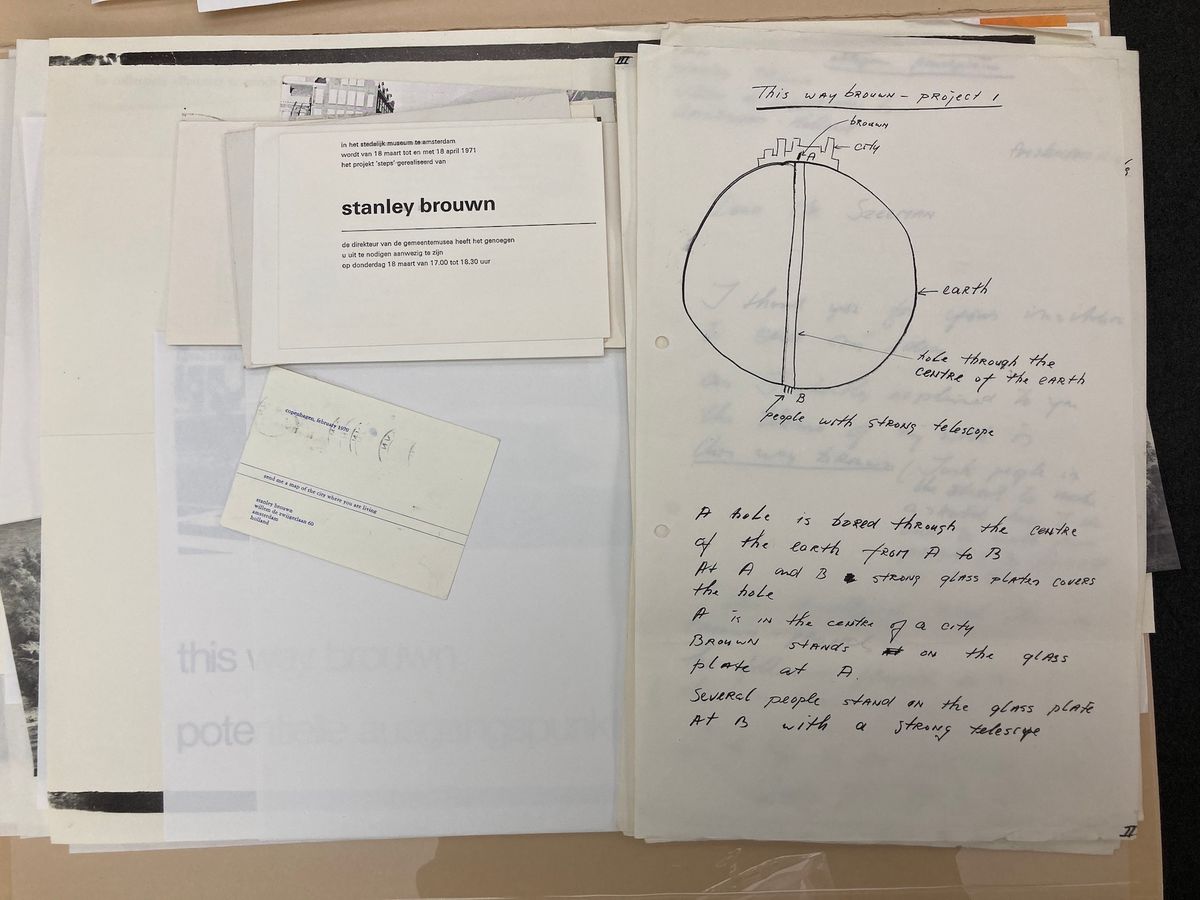

In 1969, the Suriname-born, Amsterdam-based conceptual artist Stanley Brouwn wrote a letter to curator Harald Szeemann at the Kunsthalle Bern containing proposals for four rather impossible projects. The first was to drill a hole through the center of the earth, from the center of a city where Brouwn would stand, point A, to the other side, point B. Glass plates would be installed over both holes. A “strong telescope” would be placed at point B, so people there could peer into it “and see the underside of the shoes of Brouwn”. Then, as soon as he was approached by a passerby, the artist would ask the way to another spot in the city—and walk away.

Accompanied by a sketch, the telescope concept reminded me of some of Chris Burden’s unrealised projects, but with less attention to the heavy machinery needed to move earth and more on the glancing connections between artist and passerby, and our instinctual urge to map our place in the world—both abiding interests of Brouwn’s. I found this project in the Szeeman archives at the Getty Research Institute, which I visited in March on a quest to learn more about this important but little-known artist, the subject of two shows opening in April: his first US survey, at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), curated by Ann Goldstein and Jordan Carter, and a more focused show at the Dia Art Foundation in Beacon, New York, organised by Carter.

Brouwn is little-known for a reason: he made it clear to gallerists and curators he worked with for decades that he did not want his artworks reproduced, discussed or interpreted. In group exhibition catalogues, his page was often left blank. And the upcoming exhibitions are taking place not only in the absence of the artist, who died in 2017 at the age of 81, but also without any of the curatorial, pedagogical or promotional tools that typically accompany museum shows. There will be no exhibition catalogue, no interpretive wall labels, no public programmes and no press releases.

When asked what she could share about the AIC exhibition, Goldstein responded by email: “As we are honouring the artist’s wishes concerning the representation of the work, we are quite limited in what we can share. In keeping with the artist’s wishes, all that we have shared is reflected on the exhibition page of our website.”

That site confirms the existence of the exhibition (called stanley brouwn, rendered unassumingly in lowercase Helvetica), running 8 April to 21 July, with the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Stedelijk in Amsterdam as future venues and the existence of a companion show at Dia, which opens 15 April. (At press time, an AIC publicist sent me a short “fact sheet” adding that the show “presents over 50 works from 1960-2006, representing the range of brouwn's artistic practice”.)

Goldstein and Carter then declined to speak for this article, which might be the first time in my 25 years as a journalist that curators did not welcome the chance to promote their exhibitions.

Sure, other artists have placed conditions on the exhibiting their artworks, from Bob Irwin in his early days banning photography of his installations to Tino Seghal placing restrictions on the documentation and sales of his performances. The ever-elusive David Hammons, said to be an admirer of Brouwn, routinely avoids interviews and effectively exposes the framing devices that give value to art. But short of withdrawing from artmaking in a Rimbaudian or Duchampian checkmate, Brouwn’s stance seems a more extreme form of refusal, rendering curators—who so often serve to amplify the voices of artist—pretty much speechless.

His desire to protect his artwork from interpretation—or, perhaps, preserve it for chance or immediate encounters—holds up a mirror to the limits of my work as an arts journalist as well. When I first heard Brouwn’s show mentioned in a casual conversation, it felt to me, frankly, like a challenge. What is this show that nobody is supposed to talk about and who is this artist who doesn’t want me to write about him? I have a history of investigative reporting, and I could surely find out, though perhaps the more meaningful question—one that still feels to me unresolved—is whether I should.

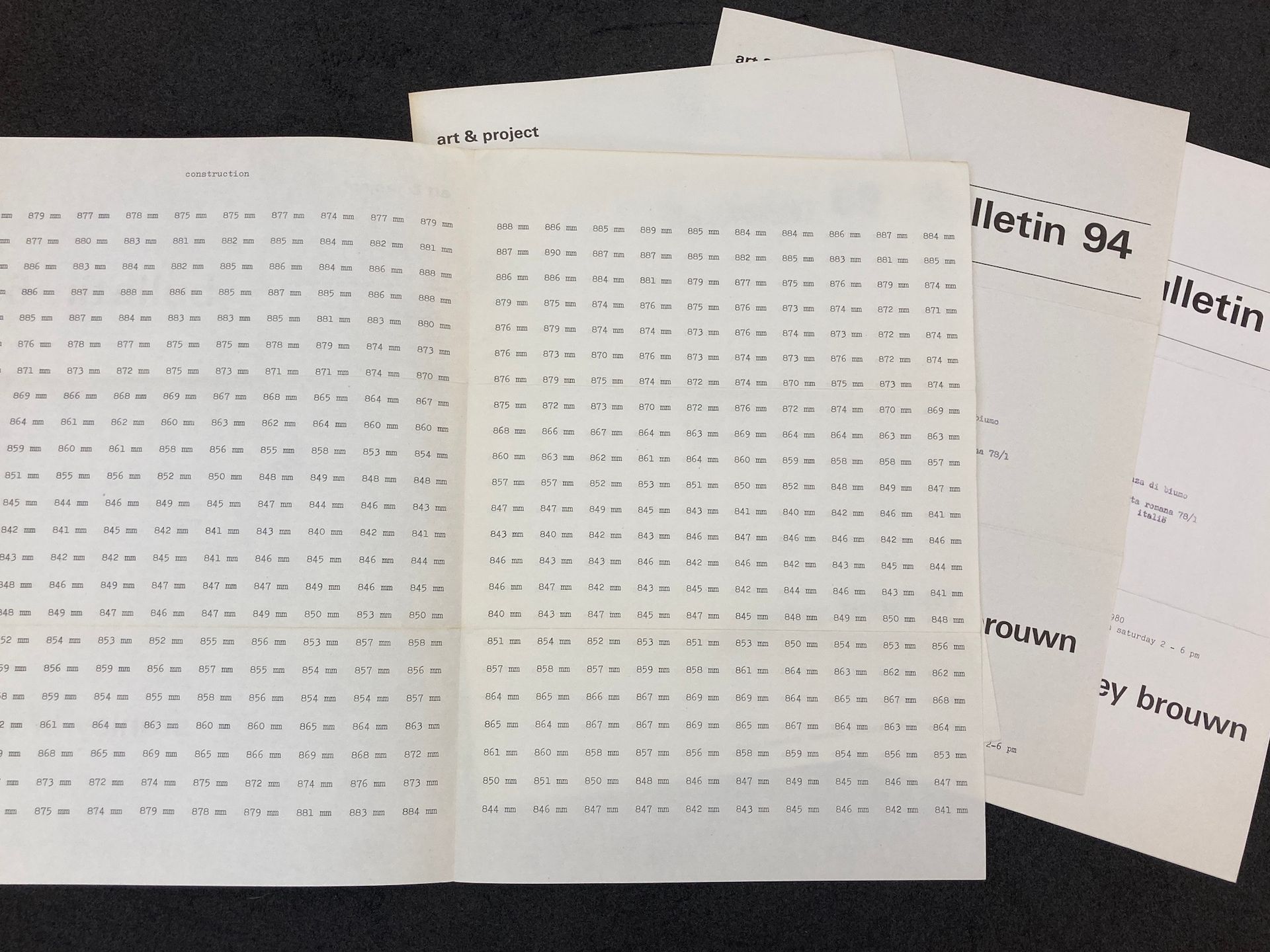

Along with making artist books, Brouwn took over several Art & Project bulletins; these belonged to collector Giuseppe Panza Jori Finkel

I started out tentatively, just asking a few friends if they knew his work. The only one who did is the artist Kim Schoenstadt, who said she learned about the work from John Baldessari when she was his studio manager. She texted me a photograph of a photocopy of a 1969 pamphlet by Brouwn, part of the influential Art & Project series of artists’ “bulletins”—a reminder of a time when xeroxing was a popular form of artistic transmission and when Baldessari would bring a black suitcase full of European art catalogues to the classroom as part of his teaching.

At that time, before the Internet made everyone a publisher, keeping things that were in public view out of public discourse was of course easier. But these days it’s strange to find this sort of information asymmetry: for an artist with such a lengthy exhibition history, including at least four editions of Documenta, Brouwn has a relatively short bibliography. Online I found only a dozen or so substantial reviews and essays, most focused on the project this way brouwn. The project featured a series of actions on the streets of Amsterdam, where he’d ask a passerby to draw directions to another point in the city and stamped their sketches with the words “this way brouwn”.

The more I learned about the work, the more questions I had. My next stop was the Getty Research Institute, where I found 13 books by Brouwn as well as material in large archives like that of Szeemann, who included his impossible telescope project in the 1969 show Plans and Projects as Art. Much of the material felt revealing and concealing at once, provocations befitting an artist who once claimed all the shoe stores in Amsterdam as his exhibition.

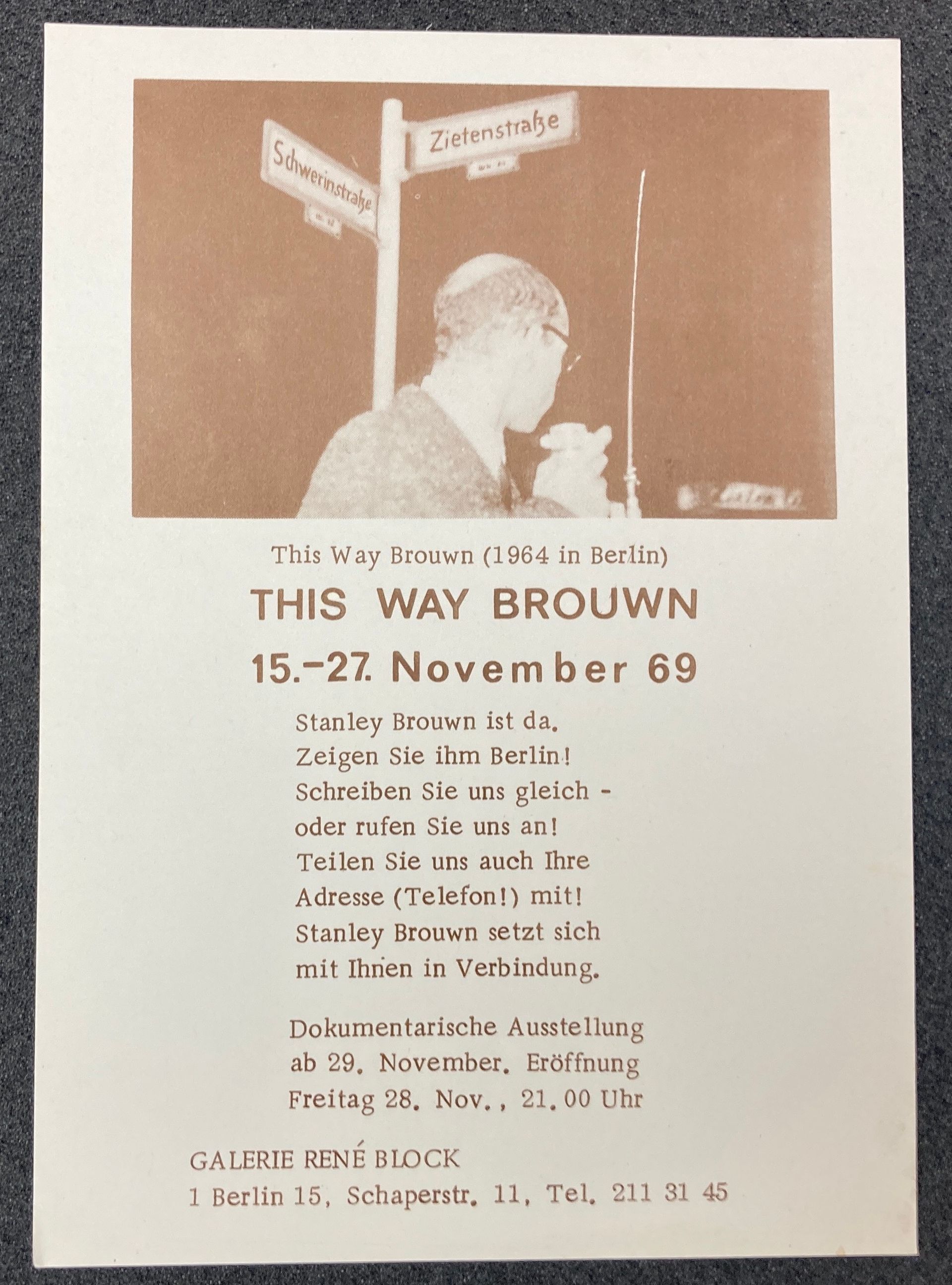

The Szeeman archive held a stack of postcards announcing Brouwn’s exhibitions at galleries like René Block in Berlin and Konrad Fischer in Düsseldorf as well as the Stedelijk Museum, and very little about the shows themselves. An artist CV in the mix had just a few lines of biography, identifying him as a Fluxus member and listing“autodidact” in place of schools.

One of Brouwn’s earliest galleries, René Block in Berlin, showed examples from this way brouwn in the 1960s, work that often involved mapping out city routes Jori Finkel

The folders of Fluxus collector Jean Brown contained a small, flat glassine bag stamped “use this brouwn”. It was empty and showed no trace of ever being used.

The archive of collector Giuseppe Panza had Brouwn’s Art & Project issues and small photographs of what I presume to be his artwork: three metal filing cabinets filled with index cards, perhaps the cards Brouwn used to record the distances of his walks through cities, sometimes using the length of his own foot (the “sb-foot”) or other body parts as the units of measurement. There was also a 1972 receipt for 960,000 liras from the Françoise Lambert gallery for My Steps in Milan, perhaps the name of this file-cabinet work.

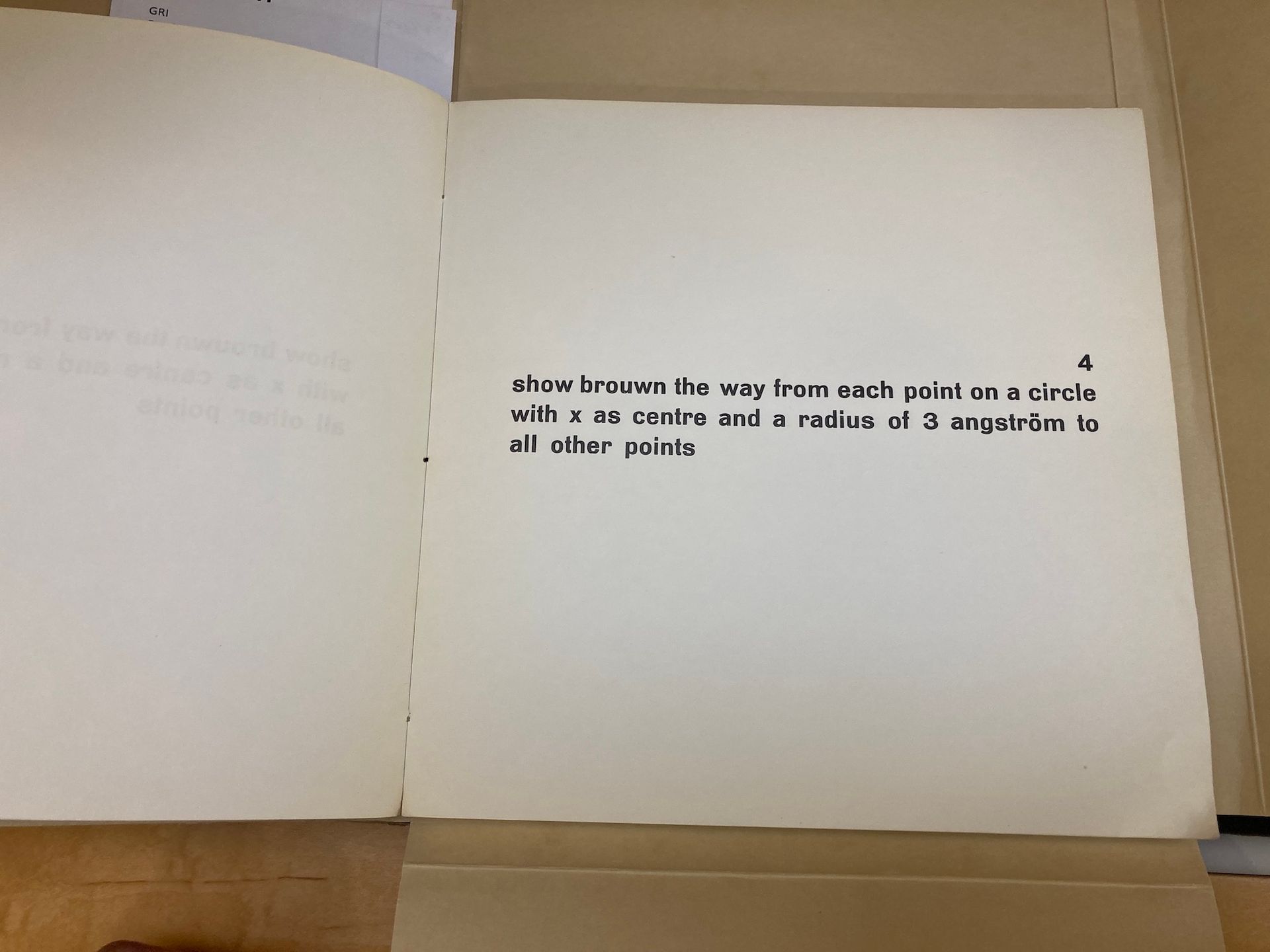

As for Brouwn’s books, most consist of typed numbers or measurements, whether arranged one per page or in dense columns and rows. They are clearly artists’ books, even when published to accompany exhibitions, and defy easy interpretation. A 1981 book called one distance consists of vertical lines, 10 per page, that measure 10cm each. A 1971 book called 1 step-100000 steps consists of rows of numbers from 1 to 100,000, filling over 100 pages. My favorite book, 100 this-way-brouwn-problems for computer I.B.M. 360 model 95, has on each page a typed computer command to “show Brouwn the way from each point on a circle” to all other points with a given radius expressed in angstroms (one hundred-millionth of a centimeter).

Knowing that Brouwn was raised in Suriname when it was still controlled by the Dutch, it could be that his insistence on being both the measurer and basis of measurement represents an attempt to flip the colonialist script whereby other people—white, European men—calculate your worth. It’s also possible to see his compulsion for counting as a psychological tic or sign of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Brouwn's book 100 this-way-brouwn-problems for computer I.B.M. 360 model 95 suggests art is a series of operations, not an object of contemplation Jori Finkel

But the IBM book points to another possibility. Maybe one reason he relied so heavily on numbers is that he saw art much like coding, as a series of operations, not an object of contemplation, and that’s why trying to extract meaning from his books is like trying to do literary analysis of a multiplication table.

In an everything-everywhere-all-at-once universe, I can imagine a different version of this article, completely disregarding the artist’s stance against interpretation, that would offer a full review of all of his artists’ books. Yet another version of this article, strictly following his restrictions, is the one that I write and then delete, word by word or with a single command, and never publish.

As it happens, I’m landing somewhere in the middle, trying both to write about Brouwn’s art and his refusal to cooperate with the cultural-knowledge-production industry that ambushes it, which of course includes my own profession of journalism.

In this way I feel like I am pointing my telescope at Brouwn. All I can see is the bottom of his shoes, before he vanishes from sight.

• stanley brouwn, 8 April-25 July, the Art Institute of Chicago

• stanley brouwn, on long-term view starting 15 April, Dia:Beacon, Beacon, New York