Sixty years after her first London show at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), the Pop Art pioneer Jann Haworth embraces a "soft and warm" fabric-centred sensibility in new works showing in Out of the Rectangle (until 13 May), at Gazelli Art House, in Dover Street. In 1963, Haworth was one of Four Young Artists showing at the then home of the ICA in Dover Street Market, just 30 metres up the street from her latest show.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, and the dislocation it brought to her daily life in Sundance, Utah, Haworth felt the need for materials "soft" and "warm", and an escape from the rigidity of stretched canvas. She steps "out of the rectangle" in her London show with six new painted fabric hangings, deliberately scaled to seem large or slightly oversize to the approaching viewer, in which the American-born artist addresses her concern with the myth of the Wild West and the American cowboy, and revisits the female corset, examining that garment's transformative power to constrain, to expand and to lie or hang flat.

"It has surprised me," Haworth told The Art Newspaper of her new, soft, fabric pieces. "Something acted differently," she says, during the pandemic. She had previously been used to working out her artistic ideas intellectually in a Sundance café, where she could sit, write and sketch for four hours at a time, with the "coffee-shop sound" around her.

“The mountains and the desert support this rainbow of colours": Jann Haworth, Detail from Colour Film Cloak, 2023, oil on cloth, with stencilled scenes from classic Wild West movies © Jann Haworth. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo by Deniz Guzel

"These works," she says, "come from a different place". An emotional one. "I am used to doing things intellectually," she says, and laughs at the imaginary picture of Harold Cohen—her famously exacting tutor at the Slade School of Art in London who went on to be a pioneer of computer art in California—wagging his finger at her for not having a clear reason for every mark that she makes in her latest work.

Untitled (Corset) (2022), strikingly placed at the back of the ground floor space, is made up of stitched lengths of painted linen and cotton, suspended on interlocking crosses, daubed in the vividly natural colours of the desert country around Sundance. In the painted lengths of cloth, Haworth told The Art Newspaper, she sometimes caught a moment of pure abstraction. The cloth strips are cut and stitched from larger pieces, where she let "splashes happen in a loose, gestural way", in the manner of Japanese calligraphy, before selecting a "highly precious" piece of the cloth and bringing it "into a straitjacket" by cutting and stitching. “I like the contrast," she says, "between that very loose event, then the very strict sixteenth-of-an-inch precision [of cutting and stitching]”.

Jann Haworth, Pandemic Blue, 2022, features in Out of the Rectangle © Jann Haworth. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo by Deniz Guzel

Another corset-themed piece, Pandemic Blue (2022), has lengths of painted cloth deeply layered and interwoven with a circular blond-wood frame. It features the same palette, one that is grounded in the warm colours of the Utah desert, contrasted with the vivid blue of a sky that was, Haworth recalls, a revelation when unpolluted by traffic and aeroplane fumes at the height of the pandemic.

“The mountains and the desert support this rainbow of colours," Haworth says. "There’s a kind of biological substance, desert varnish ... that stains the rock to Vandyke browns and blacks. All the [desert and mountain] colours are warm. It’s not lemony yellow it’s an 'ochrey' yellow. They are not cold reds. They are warm hot, cinnabar reds. Everything melds together.” She creates those warm colours with old master oils, some of them mined from the earth and part of nature's palette.

Haworth's Old Lady (1962-63), on show at Out of the Rectangle, and in an installation with Frank (1963), at the Four Young Artists show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, in 1963 © Jann Haworth. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo by Deniz Guzel; 1963 installation courtesy of the artist

Out of the Rectangle includes one of the soft stitched-cotton sculptures from Haworth's 1963 ICA show—Old Lady (1962-63)—a work which also appears in the album cover of the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967). In the cover shot famously co-created by Haworth, her then husband and fellow Pop artist Peter Blake and the photographer Michael Cooper, the figure of Old Lady is posed front right with one of Haworth's dolls of the child actress Shirley Temple, sporting a striped jersey, placed on its lap.

In the mid-1960s Haworth and Blake worked regularly with Madame Tussaud's waxworks in London, designing posters and creating installations for its charismatic managing director Peter Gatacre. Gatacre employed a galaxy of young talent including the stage designer Timothy O'Brien, who created a montage of Admiral Nelson's death at the Battle of Trafalgar. For a 1967 show at Tussaud's, Heroes Live!, Blake created a rose bower and supplied a mini dress for a waxwork of the film star Brigitte Bardot, then at the height of her fame. For Bardot's bower, Blake was inspired, Haworth recalls, by Keith Henderson and Norman Wilkinson's ravishing illustrations for a 1911 edition of Geoffrey Chaucer's translation ofThe Romaunt of the Rose.

Jann Haworth with Lady (1963), at Out of the Rectangle in 2023 and in 1963, with Frank (1963) Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo by Deniz Guzel; 1963 installation courtesy of Jann Haworth

Haworth meanwhile was making a 48-foot giant, based on the film actor Charles Bronson, to stand in the well of the three-storey main staircase at Madame Tussaud’s, its arms resting on the top balustrade. For this huge inflated figure, she cast a head over six feet tall in latex, made rainbow corduroy trousers, used stair-carpet for the belt, and a picture-frame for the belt buckle.

When they created the Sgt Pepper scenario at Cooper's studio in Chelsea, west London, Blake and Haworth used waxworks borrowed from Madame Tussaud's for the foreground figures—the four Beatles (to stand next to the flesh-and-blood Fab Four), the boxer Sonny Liston, the actress Diana Dors— as well as Haworth's soft-sculpture figures, including three Shirley Temple dolls in all.

Jann Haworth, Black and White Film Cloak (2023), left, and Colour Film Cloak (2023), at Gazelli Art House © Jann Haworth. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo by Deniz Guzel

Out of the Rectangle’s headline acts are two large, over-size cloth and canvas cloaks—Colour Film Cloak (2023), painted with oils, and Black and White Film Cloak (2023), painted with acrylics. They are kimono-like but in fact based on Haworth’s early conical dresses, designed both to hang and to lie flat.

Haworth was brought up at the heart of Hollywood, and her father Ted Haworth won an Academy Award for Best Art Direction for Sayonara (1957) and was nominated for his work on Marty (1955), Some Like It Hot (1959) and other films. Down the front of each of the cloth and canvas cloaks, and along its arms, are totem-like sequences of film stills, picked out with stencils, with recognisable scenes from the golden age of Hollywood. The stills focus on the classic cinematic westerns which helped establish the Eurocentric myth of the Wild West and the troubling “manifest destiny” of its white pioneers—as well as the high-risk lives of cowboys and the highwaymen and the Indigenous Americans who were pushed off their lands as the United States pushed West.

Jann Haworth, detail from Black and White Film Cloak (2023), acrylics on cloth, with stencilled scenes from classic Hollywood movies © Jann Haworth. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo by Deniz Guzel

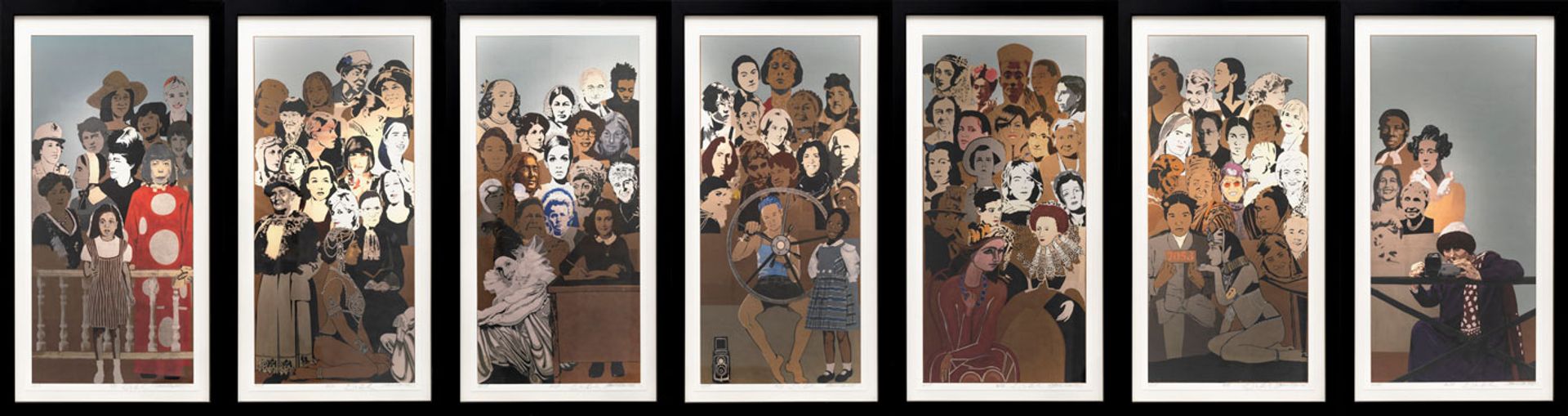

In the upper gallery at Gazelli Art House there is a series of Haworth's 2017 March works in pastel on cardboard, along with a set of prints from Work in Progress, a monumental collaborative projective which Haworth and her daughter Liberty Blake have been working on since 2016. For the project, images of women who have contributed to science and the arts have been created by more than 250 other women, many of them amateur artists. A stencil technique is used to provide a commonality of style. Haworth sees Work in Progress as a reckoning for the lack of women in the Sgt Pepper cover, and the under-representation of women in general.

Jann Haworth, a set of seven prints from Work in Progress Mural Project, 2016. © Jann Haworth. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo by Deniz Guzel

One output of Work in Progress, a vinyl version of a collage made by Liberty Blake in Utah, was featured in Haworth's 2019 retrospective at Pallant House, Chichester. Another collage from the project, featuring 130 British women who have contributed to the sciences and the arts—from Queen Elizabeth I to the sculptor Barbara Hepworth and the architect Zaha Hadid—is made up of stencilled portraits created by British artists in Utah and Britain. It was assembled by Liberty Blake and acquired earlier this year by the National Portrait Gallery, in London.

For Haworth, a champion of women and women artists over six decades, it was remarkable that the gallery should have accepted such a project blind, one created largely by amateur hands—and one that enormously increases the representation of women in the gallery's collection. “I cannot get used to the reality of the idea,” she says.

- Jann Haworth, Out of the Rectangle, until 13 May, Gazelli Art House, London