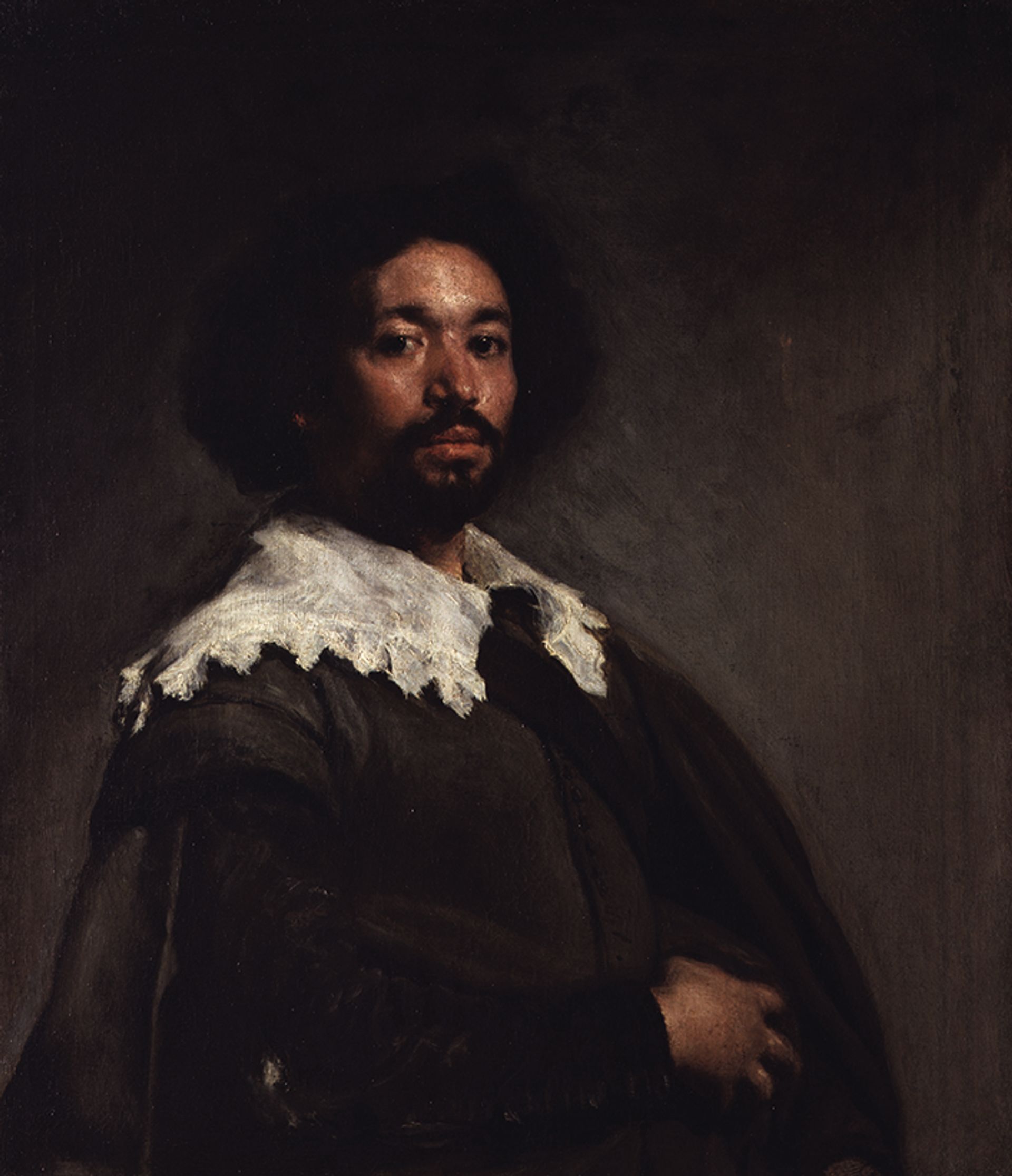

Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Juan de Pareja has been a showstopper since it first left the artist’s makeshift studio in Rome in 1650. When it made its public debut, in the Pantheon, this piercing half-bust likeness of the man who was Velázquez’s slave for two decades, was a way for the Spanish Golden Age painter to announce his artistry and arrival on the Roman art scene—one that led to illustrious commissions (including Pope Innocent X). The portrait gained more renown when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired it in 1971 for a then record $5.5m, plucking it from Longford Castle in southern England where it had been publicly inaccessible for two centuries.

The Met has since prized the painting, but its sitter, Juan de Pareja (around 1608-70), has never been the subject of major study until now. The first institutional exhibition devoted to him, Juan de Pareja: Afro-Hispanic Painter, tells the story of a man who began his own artistic career after Velázquez released him from slavery (just months after painting his portrait).

“This exhibition reframes familiar works while bringing new ones into the canon, notably Pareja’s own paintings,” says David Pullins, the exhibition’s co-curator and associate curator of the Met’s European painting department. Pareja’s works have never been assembled for a show and only one has ever been displayed in the US. Several pieces have been specially conserved, Pullins says, “to present Pareja in the best possible light as an artist in his own right rather than someone represented by Velázquez”.

The Met museum bought Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Juan de Pareja in 1971 for the then-eyewatering price of $5.5m © Metropolitan Museum of Art

The exhibition will include around 40 objects ranging from paintings and sculptures to decorative art objects, books and historic documents (such as his manumission document). Beyond presenting Pareja as a painter rather than merely a subject, the show will include representations of Black and Morisco (Muslims forced to convert to Christianity after 1492) populations in Spain by canonical artists such as Francisco de Zurbarán and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.

Determining which Pareja paintings to include in the show was complicated by the fact that his attributions have shifted over time. The scholarly monograph being published in conjunction with the exhibition addresses these and includes the first-ever illustrated catalogue of his 14 firmly attributed works. It also lists eight possible attributions and 31 works known only by texts—an impressive inventory, considering Pareja’s entire opus dates from the final ten to 20 years of his life when he was free. Listed among the works known only by written records is a portrait of Velázquez by Pareja, a curious clue imprinted in auction records that could be a fascinating complement to the former’s portrait of the latter.

For now, this exhibition unites two complementary images of Pareja: his depiction by Velázquez and his full-length self portrait 11 years later in The Calling of Saint Matthew (1661), in a similar pose and attire. At an impressive 11ft-wide, this ambitious multi-figure painting loaned from Madrid’s Museo Nacional del Prado is Pareja’s best known work. Though it depicts a familiar story, who commissioned it and its early history are questions awaiting answers.

Juan de Pareja's The Baptism of Christ (1667) © Photographic Archive Museo Nacional del Prado

After obtaining full freedom, Pareja created a style distinct from Velázquez

Scholarly study of Pareja’s life is recent. Many myths have circulated about him, one suggesting he married Velázquez’s daughter and another that he died in a duel defending Velázquez’s son-in-law. More solid research suggests that Pareja’s mother was an enslaved woman of African descent. Pareja came into Velázquez’s legal possession by purchase, inheritance or gift, a practice familiar within the artist’s family.

Another myth the exhibition hopes to expose is the extent to which enslaved artisanal labour was widespread in Spain from the medieval era to the early modern period, spanning painting, pottery, jewellery, printing, sculpture and other trades. “Sixteenth- and 17th-century Spanish visual culture cannot be disassociated from enslaved labour,” writes Luis Méndez Rodríguez, a professor of art history at the University of Seville, in the monograph.

Before setting Pareja free, Velázquez would task him with jobs such as grinding pigments, stretching and priming canvases, preparing varnishes and cleaning brushes. The manumission document stipulated four further years of enslaved service, a common practice, and in those years Pareja likely became more of an apprentice.

Pareja's Portrait of the Architect José Ratés Dalmau (1660s) Courtesy of Museo de Bellas Artes de València, photo: Paco Alcántara Benavent

After obtaining full freedom in 1654, Pareja created a style distinct from Velázquez and closer to the Madrid School painters, who used dense compositions, and Venetian-inspired colour palettes. He then worked as a painter until he died in Madrid in 1670.

Although Pareja’s story did not completely vanish from art history, it was brought to wider attention by the Harlem Renaissance collector and scholar Arturo Schomburg in the early 20th century. As part of his mission to recover the history of people of African descent in Europe in the early modern period, Schomburg became fascinated with Pareja and travelled to Spain to see his work. “I had journeyed thousands of miles to look upon the work of this coloured slave who had succeeded by courageous persistence in the face of every discouragement,” Schomburg wrote in an article published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1927.

“It was a needed act of recovery,” says Vanessa K. Valdés, a guest curator and professor of Spanish and Portuguese at the City College of New York. “Schomburg was writing only several decades after the abolition of enslavement here in the United States, in a country intent on denying Black history. For Schomburg, the importance of Pareja was not only that he existed, and as an accomplished artist in his own right, but also that he was part of a larger narrative that centred Black achievement.”

• Juan de Pareja: Afro-Hispanic Painter, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 3 April-16 July