On a cold and stormy night earlier this month in Los Angeles, heavy rain pelted the streets outside while a small mob crowded into Allouche Gallery. Heads were craning about to see the creator of the large paintings hanging on the walls—many of them landscapes verging on abstraction, and rather moody themselves. The artist, actor Sharon Stone, was holding court in the gallery’s first room, a striking figure in a black suit accented with gatherings of magenta ruffles.

The show, Shedding (until 7 April), is the first solo gallery exhibition for Stone, who took up painting—in an almost feverish way—during Covid-19 lockdowns. The title references all kinds of shedding, she says, including loss. She had become a household name for Basic Instinct (1992), in which she plays a seductive psycho-killer, but then became trapped in Hollywood stereotyping. She feels that Hollywood, which had once embraced her, has now abandoned her. “I lost my family—my film family—I lost my personal family, many members of my family died,” she says. “My brother had a heart attack and his 11-month-old son died of crib death; my godmother died, and my grandmother died.”

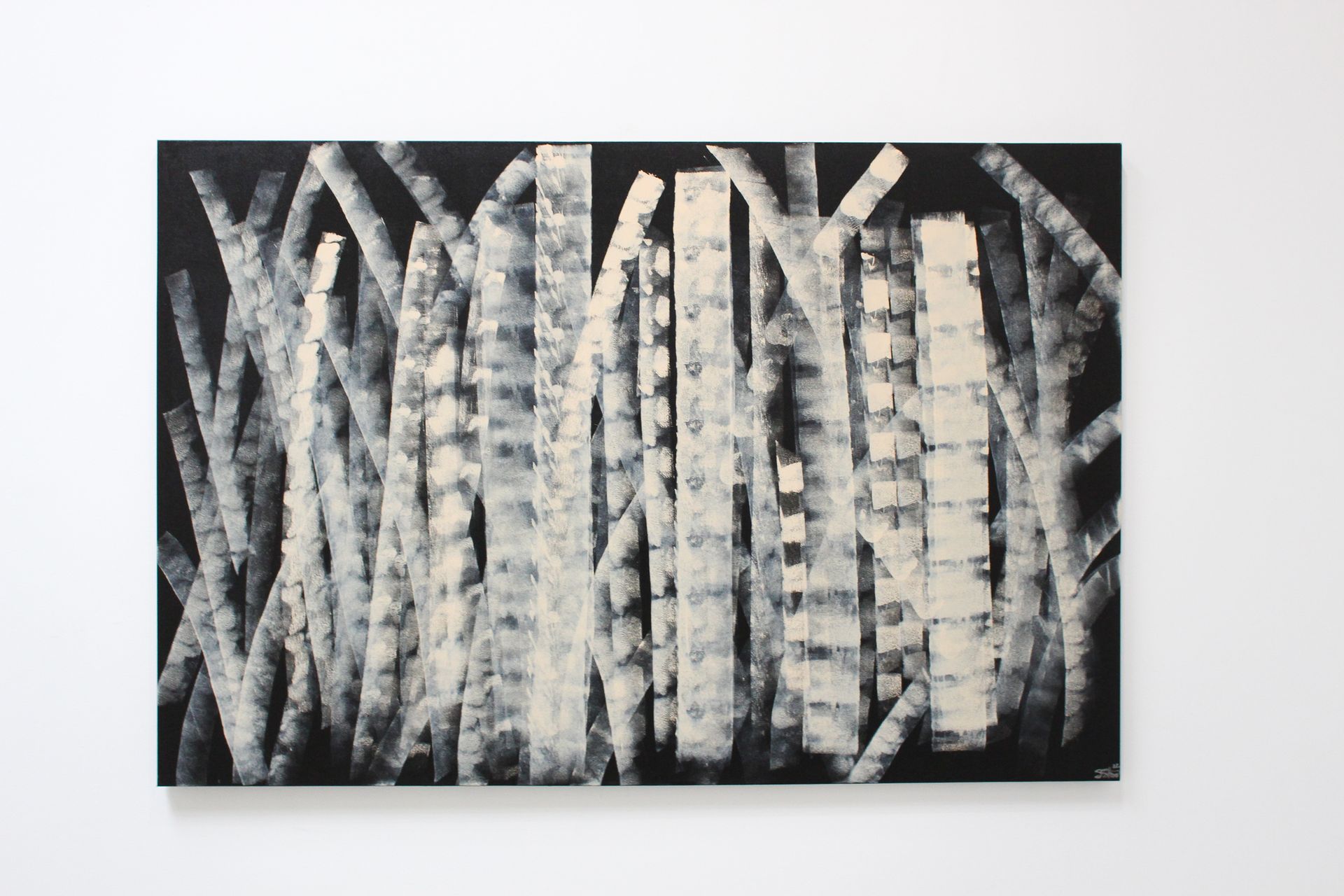

Sharon Stone, Redacted, 2022 Courtesy the artist and Allouche Gallery

Artmaking has long been a part of her life. As a child she received painting lessons from her aunt Vonne, who had studied painting and literature in college. Later, Stone also studied those two subjects at Edinboro University in Pennsylvania, her home state. But when her acting career took off, she had no time to make art, although she says some of her favourite memories during those hectic years were visiting “museums all over the world when they’re closed, which has been an extraordinary experience”.

When the pandemic began, Stone found herself stuck at home like everyone else. A friend heard her say she wanted to paint again and sent her an adult paint-by-numbers kit. “I bought real brushes and I started to regain my control, my brush movements,” she says. “I painted and painted and painted, and I refound myself. I refound my heart. I refound my centre.” At first, she painted in her bedroom, but then she set up a studio on her property and now paints every day she can.

Sharon Stone, The River, 2022 Courtesy the artist and Allouche Gallery

At Allouche, Stone’s paintings are hung in three rooms, with the large painting that gives its name to the show, Shedding (2023), an eight-foot-tall acrylic composition on canvas, in a passageway. Against a black background are sinuous coils of translucent tubes, much like the skins that snakes shed; pink, yellow and blue circles dot the surface. The River (2022) is another work close to the artist’s heart, as it was done after the death of her 11-month-old nephew. In the foreground are tall reeds and a river that winds into the distance towards a sky in which several red moons are floating. “I made that painting about our journey,” she says, “and his journey.”

For decades, Stone says, people have been telling her to “stay in your lane”. That doesn’t sit well with her. “How do you know this isn’t my lane? How do you know that painting isn’t my real lane?”

Sharon Stone, Bem Bones, 2021 Courtesy the artist and Allouche Gallery

- Sharon Stone: Shedding, until 7 April, Allouche Gallery, Culver City, Los Angeles