“The thing about sculpture that is particularly my passion… is whether the work can be on the edge of knowing what it is and what it could be or might be,” Phyllida Barlow told The Art Newspaper in November 2013. “In other words, that extraordinary question of, ‘Is it finished?’ There is a tradition of that, through Arte Povera, Giacometti, Rodin, even in some of Michelangelo’s blurred figures emerging from the stone—it’s a wonderful aspect of sculpture that defies the monumental. Jeff Koons is a magnificent example of somebody whose work absolutely has complete resolution. But they operate more as pictorial events for me than sculptural events.”

She managed to achieve at once awkwardness and grace, humour and pathos, the grand and the intimate

These words reflect many of the qualities that made Barlow one of the most significant British artists of recent years. Ardently committed to sculpture and convinced of its special power, she was coruscatingly erudite and perceptive, yet also irreverent and suspicious of orthodoxies. This was evident in her combinations of simple materials such as wood, plaster and scrim, cement, paint and fabric. She managed to achieve at once awkwardness and grace, humour and pathos, the grand and the intimate. Hints to a deep knowledge of other artists abound in her work, yet hers was a singular language. She used exhibition space dramatically—with sculptures stretching to its heights and depths, occupying its walls and lurking in its corners, as if they were living entities feeling their way around, testing its parameters.

Barlow was a student first at the Chelsea School of Art, in London, and then the Slade School of Art, London University

A Chelsea student

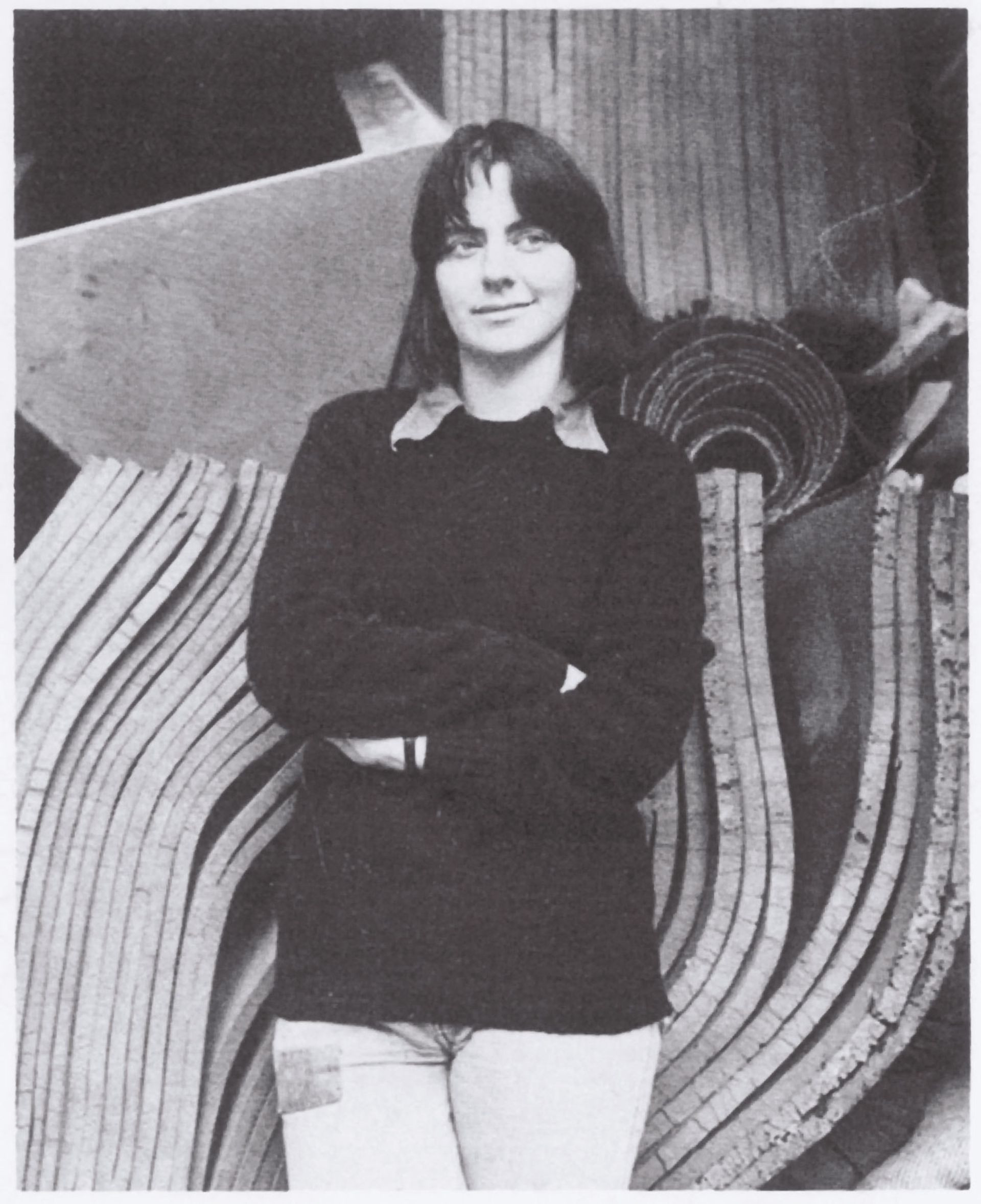

Barlow was born in 1944 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where her father Erasmus Darwin Barlow, a great-grandson of Charles Darwin, was a psychiatrist researching brain trauma. Phyllida spoke often of childhood memories that related to the themes and forms of her work, like urban clamour, destruction and accumulation. She remembered the “very strong experience” of Erasmus taking her and her siblings on drives into London’s bomb-damaged East End and of her grandmother’s cupboard under the stairs, where “she kept every single thing that could be reused”.

From 1962, Barlow studied at Chelsea School of Art, where she met Fabian Peake, her artist husband, himself from a distinguished background—he is the son of Mervyn Peake, author of the Gormenghast fantasy novels. They married in 1966. From Chelsea she went on to the Slade School of Fine Art, London University. Her tutors could be supportive, like George Fullard and Elisabeth Frink—“that’s great… carry on”, she recalled them saying—or shockingly dismissive, like Reg Butler, who told her: “I’m not that interested, because by the time you’re 30 you will be having babies and making jam.”

Phyllida Barlow, installation view of dock, part of the Duveen commission, Tate Britain, 2014 ©2014 Alex Delfanne; courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

An “astonishing morality” governed her discipline at the time, “where one was having ‘real’ sculpture shoved down one’s throat—it was either good or bad or it was right or wrong, and it was a complete turn-off to me”. A “youthful anarchy” led her to embrace emerging tendencies including, in Britain, the New Generation, as shown at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1965, by artists such as David Annesley, Michael Bolus and William Tucker. But she was principally inspired by overseas movements. Though “all eyes were on America” and Minimalism and Conceptualism, she recalled, “I was turning as much to Europe and trying to glean as much information as I could”. This would be mostly from texts and images in magazines. Artists she discovered then, from Louises Nevelson and Bourgeois to Germaine Richier and, later, Eva Hesse, remained touchstones throughout her career.

The Slade School and beyond

Barlow became a tutor at the Slade in the late 1960s, and continued to teach until 2009. She and Peake also brought up a family of five after 1973. The Peakes are all artists of different kinds: Eddie and Florence are best known for their performance work, Clover is a poet and designer, Tabitha a painter, and Lewis a concept artist and illustrator for films. Much has been made of Barlow’s frequent contention that “children and being an artist are very incompatible”, but she also credited the experience of parenthood with the urgency it brought to her work. “For me and for Fabian, it was a huge training ground that we’re able to use even now; that you grab every moment you’ve got.” Encountering Barlow in the studio, there was no doubting how fully she threw herself into her activities—her clothing was caked in paint, plaster, cement and more.

Between the 1970s and 2000s, presentations of her work were often self-generated, in an abandoned attic, a school playground, a disused office, an old stocking factory, even thrown into the Thames. She had begun to show more in the 2000s before she retired from teaching, but big success occurred once she became a full-time artist in 2009. A show at Studio Voltaire in south London in 2010 was followed the same year by a brilliantly conceived pairing at the Serpentine Gallery with the Iranian-born sculptor Nairy Baghramian. Baghramian had written in Artforum the previous year of an epiphanic visit to Barlow’s London home where she saw “rough and provisionally taped-together structures”; it was “as if reality could not yet accommodate these still-malleable ideas”, she wrote.

Phyllida Barlow, installation view at the exhibition Phyllida Barlow—Cast, Kunstverein Nürnberg, Germany 2011 © Stephan Minx; courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Towering blocks on stilts

A huge shift in Barlow’s life and career came when Hauser & Wirth started to represent her around the same time. Her first show with the gallery was in 2011 in a space it had at the time in an Edwin Lutyens-designed former bank in Piccadilly. It was a magnificent exposition of Barlow’s engagement with space, with towering blocks on stilts in the principal room, anthropomorphic hoops huddled in a downstairs lobby, and pom-poms in the attic. Though she continued to make small works and marvellous drawings, Barlow was able to be increasingly ambitious in terms of size (she disliked the word “scale”). “I love big sculpture,” she said. “I like that sense of my own physicality being in competition with something that has no rational need to be in the world at all. And that is in itself just an expression of the human condition, of who we are and what we are.” The big ideas came thick and fast even though she modestly described her existence as “a very small life… it’s family, studio and Tesco [supermarket] really”.

I like that sense of my own physicality being in competition with something that has no rational need to be in the world at allPhyllida Barlow

An imaginative engagement with the environment and people around her was key. She said her sculptures absorbed “the flukes and the chances of how things encounter each other physically in the world”. She was clear that her sculptures were metaphors for experiences rather than similes. When the work could “just be itself and stubbornly refuse to be like anything else”, she explained, “I think it’s getting somewhere”.

This was evident in an extraordinary series of works made in the 2010s, from Tip (2013), a forest of cement, timber, steel mesh and fabrics that flowed out from the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, to dock, her show cramming into the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain in 2014, and, perhaps most notably, her 2017 work folly, filling seemingly every inch of the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale. In each case, she took on loaded spaces: the ghosts of artists past at the Carnegie and Tate, the national pavilion of Britain in the year after Brexit—an event that appalled her—with characteristic boldness and risk.

Phyllida Barlow, installation view of dock, part of the Duveen commission, Tate Britain, 2014 ©2014 Alex Delfanne; courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

An unwavering commitment to irreverence

Folly was the zenith of Barlow’s total environments, after which, she said, “I just drew a line under it and started to think very much about the single object”. But shows at the Royal Academy in London (2019) and Haus der Kunst in Munich (2021), among others, showed that her commitment to imposingness and irreverence remained unwavering.

Part of Barlow’s brilliance was in judging how far to go too far (to quote Jean Cocteau) with her audience, in order “not to get trapped in an exploitative emotional blackmail where you’re vomiting on people’s shoes and expecting to be pitied”, Barlow said. “It’s a fine line where something that might seem awkward, ungainly or ugly can also have some kind of compassion about it. That, for me, is where the balance is.”

Phyllida Barlow, installation view, tryst, Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, Texas, 2015 Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In fact, Barlow was avowedly generous, empowering her viewer. She described the encounter of audience and sculpture as a “meeting”. Coming face to face with her works, “which then have to be walked around or looked into or up to”, she said, “is a performative act, not a passive act”.

Gillian Phyllida Barlow; born Newcastle-upon-Tyne 4 April 1944; RA 2011; CBE 2015; DBE 2021; married 1966 Fabian Peake (three daughters, two sons); died London 12 March 2023