The legendary Linton Kwesi Johnson, renowned as the voice of Britain’s post-Windrush Generation and who pretty much single-handedly defined the term “dub poetry”, has been straddling creative disciplines for decades. Kwesi Johnson came to Brixton, South London from Jamaica in 1963 and joined the Black Panthers while still a schoolboy. Early on, his words of anger, struggle and defiance delivered in his signature London-Jamaican-patois were often performed over the pulse of a reggae beat, resulting in a clutch of groundbreaking albums in the late 70’s and early 80’s, including Dread Beat an’ Blood (1978); Forces of Victory (1979); Bass Culture (1980) and Making History (1983).

The influence of the 70-year-old also extends throughout several generations of the British art world. When Yinka Shonibare coordinated the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition, he invited Kwesi Johnson to read Di Great Insohreckshan, his poem that addresses the Brixton riots in 1981, as part of the academy’s Sound Programme. Steve McQueen also used Johnson’s poetry in his acclaimed BBC drama series Small Axe (2020); and commissioned a new poem, Towards Closure, for his three-part documentary series Uprising (2021). But Kwesi Johnson had already made forays into contemporary art: back in the early 80s he organised an open exhibition of Black British art with the aim of platforming art in tune with the struggle for racial justice that included Keith Piper, Eddie Chambers and Sonia Boyce.

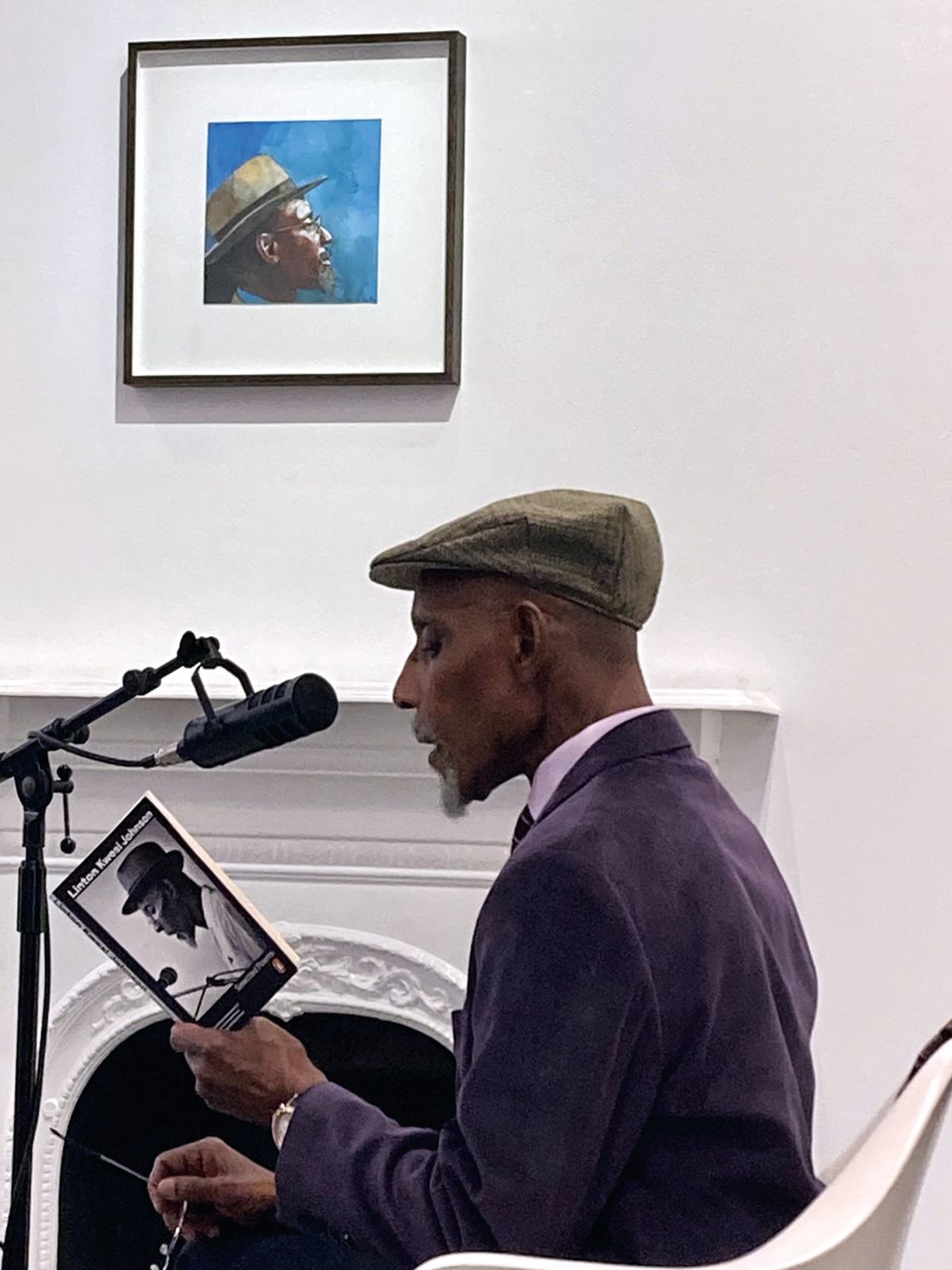

Peter Doig and Linton Kwesi Johnson

Photo: Louisa Buck

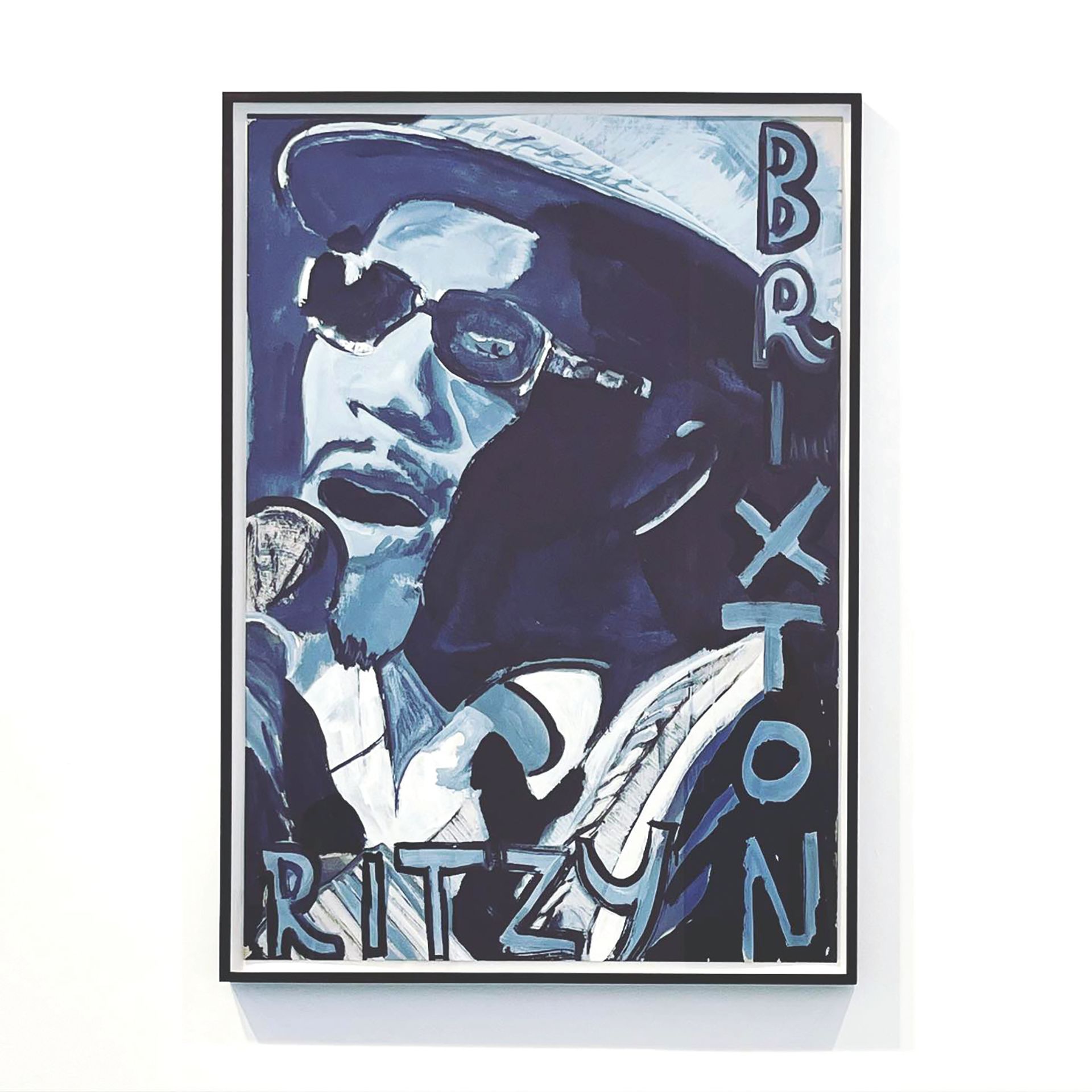

It was also around this time that a youthful Peter Doig went to see Kwesi Johnson performing at the Ritzy in Brixton. “One of the musicians whose music led me to London was Linton,” Doig tells me. “I first saw him in 1980, the year after I arrived from Toronto.” Doig still vividly remembers the Brixton gig as “a powerful performance as much as a concert: LKJ had this kind of non style stylishness… he did not look like a musician—either from reggae or the pop worlds—his words were spoken, which really suited his appearance, a bit like a cool teacher. His music still sounds as fresh and surprising today as it did back then.”

Another longstanding LKJ fan is Sir Peter Blake, the nonagenarian grand old man of British pop art, who remembers seeing Kwesi Johnson supporting Ian Dury and the Blockheads at the Hammersmith Palais in 1979 and being so enthused that he returned for seven nights in a row.

Blake’s 2020 watercolour portrait head of Kwesi Johnson, along with a new painting by Peter Doig commemorating that long-ago Brixton gig, are currently on show in The Wisdom Man, at Paul Stolper Gallery, an exhibition that pays timely tribute to Kwesi Johnson’s pivotal and enduring cultural role within the UK and beyond. There are also etchings by Kwesi Johnson’s near-contemporary, Denzil Forrester, a knitted yarn portrait by musician Rod Melvin (who also played with Ian Dury) and a bronze bust and two paintings by Errol Lloyd, the London-based, Jamaica-born artist who was a key member of the Caribbean Artists Movement and remains a longstanding friend of Kwesi Johnson.

Peter Doig's new painting commemorating Kwesi Johnson's Ritzy gig

Other works include Petra Börner’s portrait collage of Kwesi Johnson that was used for the cover of his 2006 anthology published by Penguin books, and a trio of distinctive bearded portraits by Derrick Alexis Coard that the late artist described as “a symbolic expression for possible change for the African-American male community”.

Doig, Blake and Errol Lloyd were all in attendance at the show’s packed opening, which was also memorably marked by the ever dapper presence of the Great Man in his trademark suit and cap. With characteristic modesty, Kwesi Johnson declared the show “a golden opportunity” to showcase the work of his friend Errol Lloyd, declaring, “That’s why I’m here.” He then mesmerised the room with three poetic elegies to his father, his nephew Bernard and the Afro-German poet May Ayim, as well as a recent poem written in Brixton, in the midst of the pandemic, to the ominous backdrop of “di unrelentin’ wailin’ soun’ of sirens”.

Afterwards, in conversation with Roger Robinson, the British-Trinidadian writer, performer and winner of the T.S. Eliot poetry prize (who said he “wouldn’t have written anything without LKJ”), Kwesi Johnson reaffirmed that, despite having played with everyone from Pete Tosh to Gil Scott-Heron and Siouxsie and the Banshees, and having been offered—and turned down—a multiple album deal from Island Records, nonetheless “the music was just a way to reach more people”. With LKJ, it has always been the words that come first, as he puts it, “writing was a political act and poetry was a cultural weapon.” And right now, we all need his words more than ever.

• The Wisdom Man, Paul Stolper Gallery, London, until April 21