A major work by Bill Traylor (around 1853-1949), a self-taught artist who was born into slavery and developed a striking and unique style of figurative painting late in life while living on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, has been donated to the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM) in New York.

The untitled composition on cardboard, which brings AFAM’s holdings of Traylor’s work to four pieces, previously belonged to Lanford Wilson, a playwright who won the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1980 for his romantic comedy Talley’s Folly and died in 2011. It was given to the museum by Tanya Berezin, an actress who, along with Wilson, co-founded the renowned Circle Repertory Company (which operated in Manhattan from 1969 to 1996).

“When Tanya Berezin offered it to the museum, I could not believe it was true—it’s a masterpiece,” says Valérie Rousseau, AFAM’s senior curator of self-taught art and art brut. She adds that between the prevalence of fake Traylor works circulating in the market, and the enormous value of his authentic work (his current auction record is $507,000), the possibility of such a piece being offered to the museum seemed outlandish. “I thought it was a joke.”

The painting, executed in graphite and poster paint on cardboard, is officially dated to between 1939 and 1942. As is typical of Traylor’s work, it is untitled, though the descriptive subtitle added by a dealer, “Blue Construction, Figures, and Bottles; or Two Men Reaching for Bottles”, has been retained. It has several features that are quintessential of the artist’s practice, foremost among them the dominant shade of cerulean blue that was a trademark of the artist’s iconography.

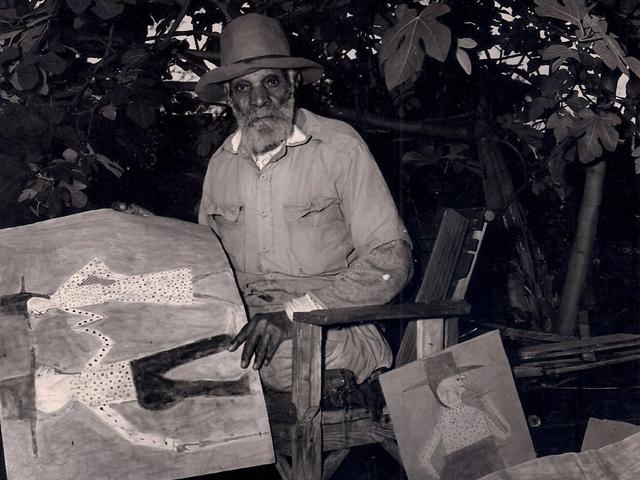

The painting depicts two figures reaching for bottles of moonshine on a high shelf. The larger figure in the image, which stands atop a platform and sports brown trousers, may be a self-portrait, according to Rousseau. “Because of the beard, because of the hat,” she says. “We’ve seen photographs of Bill Traylor in the streets of Montgomery and specifically sitting in front of the general store, which are very close to the traits of this figure.”

The second, smaller figure, a kind of miniature or alter ego of the main figure whose pose it mirrors, recurs across many of Traylor’s works as a mischievous character. Rousseau adds: “This specific work exemplifies the strength of his style that we are all admirative of, the way that he is creating these tensions by placing the figures and motifs into very specific configurations.”

Traylor’s work has been featured at various times at AFAM, including in two concurrent solo exhibitions in 2013. A reproduction of the newly acquired work was also featured in Bill Traylor, a 2018 book by Rousseau, Debra Purden and Margit Rowell. Even so, Rousseau is eager to become better acquainted with the work, including examining its back more closely. Doing so, she hopes, will offer insights into how it was displayed, promoted and ultimately sold, via New York’s Hirschl & Adler Galleries, by the man who took much of the credit for bringing Traylor’s work to a wider audience.

“Charles Shannon started to collect Bill Traylor’s works on the streets of Montgomery in 1939, which must have been the year Traylor started to work,” she says. After showing and attempting to sell works from the trove of 1,200 Traylor pieces he had bought, without much success, Shannon sat on his collection for several decades before devising a new tactic.

“In the 1970s he started to reconsider the approach he would take in the coming years, and he started to divide this entire collection of 1,200 works into micro-collections,” Rousseau says. “And he was trying to have in each of these micro-collections representative examples that could be similar in each collection. So what I want to see on the back is which collection this work belongs to.”

Eventually, one day, she would like to display the newly acquired work with its “sisters and brothers” from Shannon’s micro-collection.