For more than half a century Marc Camille Chaimowicz has been hugely influential in dissolving the boundaries between art and design, as well as between the public and the private. His work combines sculpture, performance, installation, architecture, painting and photography with fashion, textiles and interior design.

Born in post-war Paris in 1947, Chaimowicz moved to London as a child but has always drawn extensively on his French cultural heritage, whether the intimate interiors of Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, the effete dandyism of Jean Cocteau or the writings of Gustave Flaubert, Jean Genet and Marguerite Duras. This erudite embracing of the decorative and the domestic has included making his modest South London apartment into an all-encompassing Gesamtkunstwerk, part of which is now on show in Nuit Americaine, his solo show at the Wiels art centre in Brussels.

This is one of his two European exhibitions that overlap this month, the other being Zig Zag and Many Ribbons at the Musée d’art Moderne et Contemporain in Saint-Étienne, Chamowicz’s first institutional show in his native France.

Chaimowicz’s post-pop scatter environment Celebration? Realife Revisited (1972-2000) Stefan Altenburger Photography

The Art Newspaper: Each of these two exhibitions span your career in different ways. At Saint-Étienne around 80 of your works dating from the 1960s onwards are combined with 30 or so artworks and artefacts from the museum’s collection in a series of environments and mise-en-scènes described as “discrete dramas”. What was your aim here?

Marc Camille Chaimowicz: I’ve long wanted to do just one museum show in the country of my birth. It’s over seven galleries, grandiloquent and it took many years. Because of Covid it was a slow burn. Apart from one or two new works, it largely meant orchestrating pre-existent work and was quite a finely honed, academic exercise. It also gave me the opportunity of showing some of my late mother’s work, which I really enjoyed. When, pre-Covid, I visited Saint-Étienne and picked up on their multifarious collection, I had this moment of insight: given that I always like to guest somebody, why not show mother?

What form do your mother’s works take?

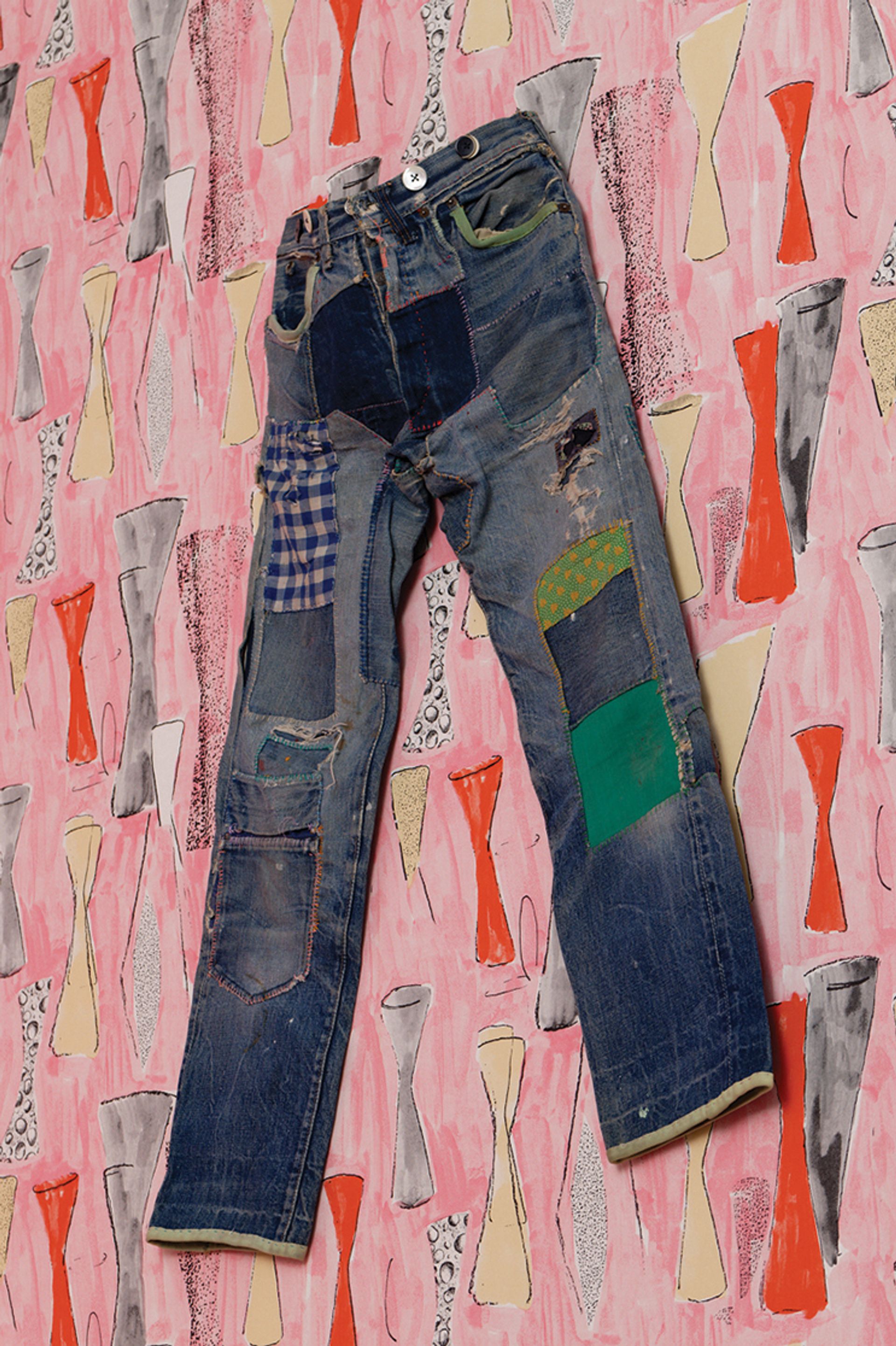

As a young woman, mother had been instructed to take an apprenticeship as a dressmaker in the couture House of Paquin. She made these beautiful sewn patterns as exercises: they were a kind of devoir, a rite of passage. I was touched that she should have given them to me rather than to my sisters—I think she’d picked up on the fact that I was into visual matter and also textiles. I’ve had them for many years and have been delighted by them. They are a cross between Agnes Martin and Louise Bourgeois. They’re fabulous.

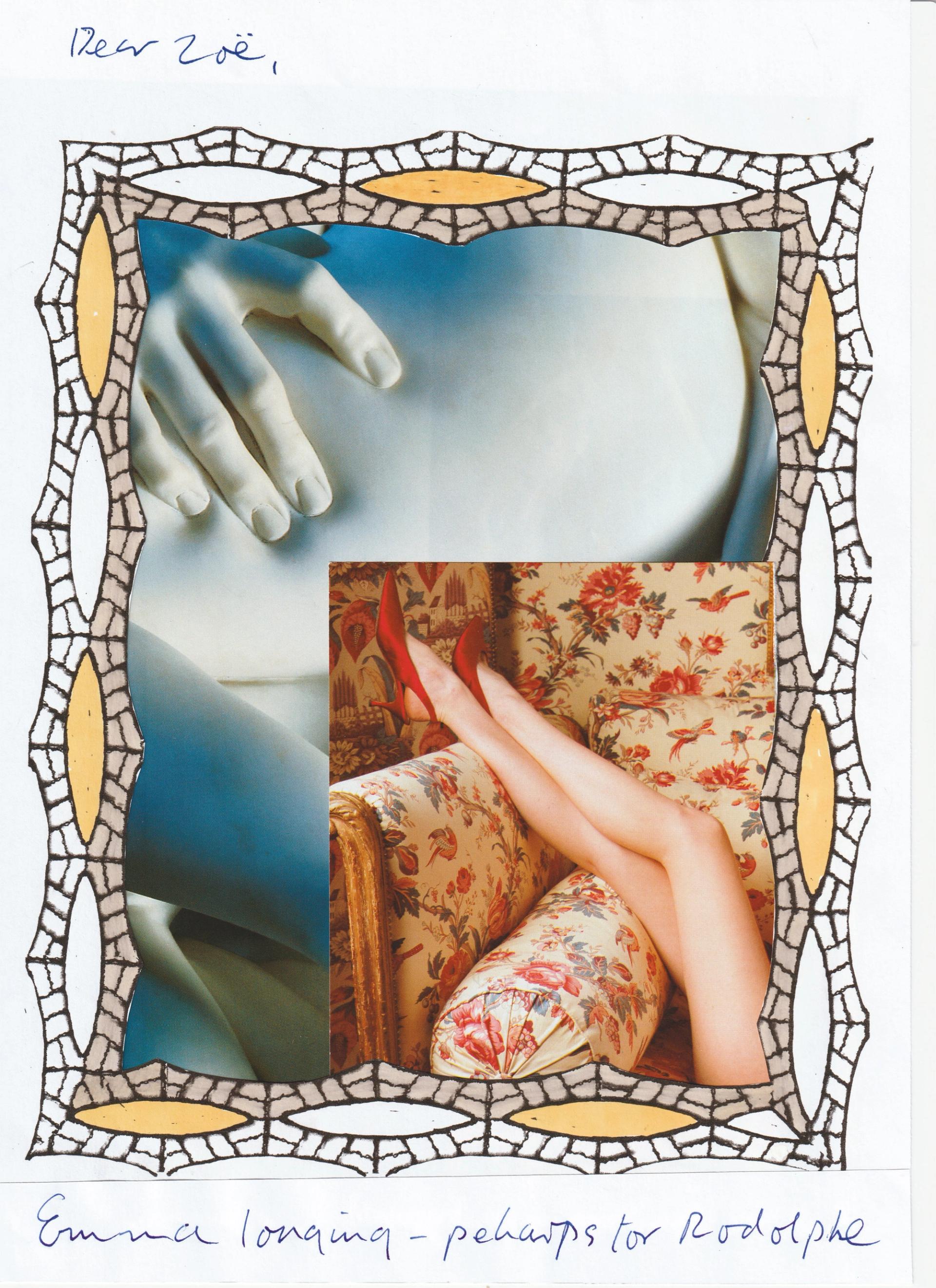

Dear Zoë (Emma Bovary collages) (2021)is being exhibited in Brussels Courtesy of the artist and Cabinet

By contrast your Wiels exhibition consists of just three works: your post-pop scatter environment, Celebration? Realife (1972); The Hayes Court Sitting Room, which takes the front room of the flat in Camberwell, South London, where you lived and worked for more than four decades and reinstates it as an art installation; and finally Dear Zoë… (2020-23), a suite of 40 collages that uses Flaubert’s heroine Madame Bovary as a starting point.

If we were to use categories of genres, one could argue that Celebration is a kind of landscape, The Hayes Court Sitting Room an interior, and the collages are portraiture. However much we wish to undermine our training and the ubiquitous history of art, I think one is inevitably reined back into those kind of references.

But at the same time, you have been a pioneer in challenging the categories of art, décor and design in your practice. Why has this been so important?

It came out of an early engagement with feminist theory. Because it was so male-driven, and black and white, the dominant left-wing ideology seemed as alienating as what it was contesting. Colour was seen as decadent and pleasure as reactionary, and for me that had to be recalibrated. And so domesticity became a sort of metaphor for me. I was also questioning the very function of visual art practice and its implicitly elite role in the canon.

Camberwell School of Arts in the 1960s was hierarchical and the applied arts were seen as taboo. I was interested in questioning that, and so in the 80s I took up volunteering as an intern in one of the last remaining traditional silk design studios in Lille. It completely undermined the hallowed ground upon which painting has always been upheld, and instead you’d do a drawing and the team would try it out. This gave me the confidence to engage in a very wide range of materials with the benefit that I could often use the skill of others. There would be dialogue and discussion, and this continues to the present day.

Chaimowicz’s Emma & Freddie in the Hayes Court Sitting Room (2022) Photo © Mark Blower; courtesy of the artist and Cabinet

As well as collaborating with artisans and craftspeople, and “guesting” other artists—ranging from Alberto Giacometti and Pierre Bonnard to Wolfgang Tillmans, Lucy McKenzie and now your mother—you often also devote entire exhibitions to admired figures, such as Jean Cocteau or Jean Genet. In many ways yours is a very sociable practice.

I was always suspicious of the studio. I felt it was a kind of trap

I guess I was always suspicious of the studio. I felt it was a kind of trap. And likewise, my current studio in Camberwell, I avoid it religiously. I store things there and I occasionally have people come in and help make work, but I’m still much at my best working on the kitchen table. So deep down there has long been this yearning for a degree of conversation, literally or metaphorically.

You were born in post-war France to a Polish Jewish father and a French Catholic mother, but when your father got work in the UK you moved as a child from Paris to England, first to Stevenage and then to Ealing in West London. Yet, although you grew up in the UK, your French cultural heritage has always played a major part in your work.

At Camberwell [art college] the dominant value was a parochial, figurative, Euston Road [School] kind of aesthetic. And, of course, I rebelled against that. As a way of rebelling, one would be drawn I guess to American practice, but large-scale abstract painting was just utterly alien to me. So that drove me back to a European sensibility. I was drawn to a very wide range of artists from Vuillard to Fragonard. But first and foremost it was probably to [the film director Jean Luc] Godard, as well as to literature and French thought, people like [Marguerite] Duras and Simone [De Beauvoir]. The theory came later.

It’s interesting that you describe your Dear Zoë… collages as a self-portrait even though they are inspired by Emma Bovary, whereas the earlier photographs and films in which you physically appear seem more to do with role-playing and tropes for ideas of the romantic, androgynous artist.

Yes, in a Bowie-like way they are often behind a form of mask. When I was doing live work, I would find a means by which to avoid anything overtly confrontational, so I’d either be in shadow or walking. I’m happier dealing with the portraits of others than I am of my own, and that’s partly why I so enjoy working with Emma Bovary.

Art School Levi’s (around 1960) and Vase (2005) are on show in Saint-Étienne Courtesy of the artist and Cabinet

You had already illustrated Madame Bovary for Four Corners Books in 2014. Was this recent series of collages, which you began after the first lockdown, a form of personal response to Emma’s feelings of entrapment and longings of escape?

There was almost inevitably a degree of projection and implied symbiosis. During that time I was also processing, editing and jettisoning a lot of magazines and visual material from Hayes Court and that fed into the Emma collages. Right now, while Emma is in residence in Brussels, I’m giving it a pause. But I think there’s still mileage left and I’ll probably pick up again afterwards. And then we’ll see where that goes.

Biography

Born: 1947 Paris

Education: 1964-68 Camberwell School of Arts; 1968-70 Slade School of Fine Art

Key shows since 2000: 2002 Ikon Gallery, Birmingham; 2003 Norwich Gallery; 2011 Nottingham Contemporary, Wiener Secession; 2016 Serpentine Gallery, London; 2018 Jewish Museum, New York; 2020 Kunsthalle, Bern

Represented by: Cabinet Gallery, London; Galerie Neu, Berlin; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; House of Gaga, Mexico City and Los Angeles

• Zig Zag and Many Ribbons, Musée d’art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Étienne, until 10 April

• Marc Camille Chaimowicz: Nuit Americaine, Wiels, Brussels, until 13 August