This month, the UK-based National Lottery Heritage Fund will announce significant changes to its funding priorities in order to address the concerns that people have for the health and future of the nation’s heritage.

Heritage organisations, including museums and galleries, have faced two turbulent years. Although many gained support from the Heritage Fund’s Emergency Fund and Cultural Asset Fund, the fund has found that nearly half still fear for their long term future.

Next year, the UK National Lottery will be 30 years old. Established by the Conservative government of John Major to generate money for good causes, it has had a vast impact on the cultural life of the nation. One of the original “good causes”, heritage receives 20% of revenue, and, since 1994, more than £8.6bn of Lottery players’ cash has been invested in around 50,000 heritage projects across the UK. The heritage money is distributed by the National Heritage Memorial Fund, under its brand, the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

From threatened toads to castles

These days, “heritage” has a very wide definition. It can mean almost anything from the past which people today want to preserve and enjoy. This ranges from threatened toads and orchids to masterpiece paintings, castles, cathedrals, churches, museums, galleries and archaeological sites. One of the strengths of the fund is that, from its inception, it has always been open to suggestions as to what it should support.

But the Heritage Fund is restricted to providing project funding, and over the past three decades it has supported almost every museum and gallery in the UK. A recent spectacular example is the £16.5m grant for the refurbishment of the Burrell Collection in Glasgow. Over its life, the fund has seen good times and bad for heritage: there have been times when capital was relatively easy to raise and operating environments were favourable. But the early 2020s don’t seem to hold such promise.

Project funding for heritage bodies is increasingly difficult to come by. Canny organisations have managed to access regeneration funding from central and local government, positioning themselves as contributors to the local economy. Levelling up grants and high street regeneration funds, for instance, are large and need to be spent quickly, mostly on new build projects. It is far harder to raise money for conservation, restoration or acquisitions. This is especially the case as some of the larger trusts and foundations, and many individual philanthropists, are tilting their priorities away from heritage to environmental and humanitarian concerns.

At the same time, many museums, galleries and heritage attractions are still emerging from the shock waves of serial lockdowns. The remarkable Culture Recovery Fund, launched by the UK government in 2020, unquestionably saved many of these from ruin. The Heritage Fund distributed more than £155m for the Department for Culture, Media and Sport to organisations that had torn through their reserves and faced imminent closure. But the subsequent pressures of energy price rises, wage inflation and crises of consumer confidence have prolonged a period of deep uncertainty for many heritage sites.

For those institutions with major projects underway, inflation and turmoil in the construction industry have presented a huge challenge. The fund has around 2,500 projects in delivery and has already had to make available more than £46m of grant increases to cover cost over-runs.

A change of approach

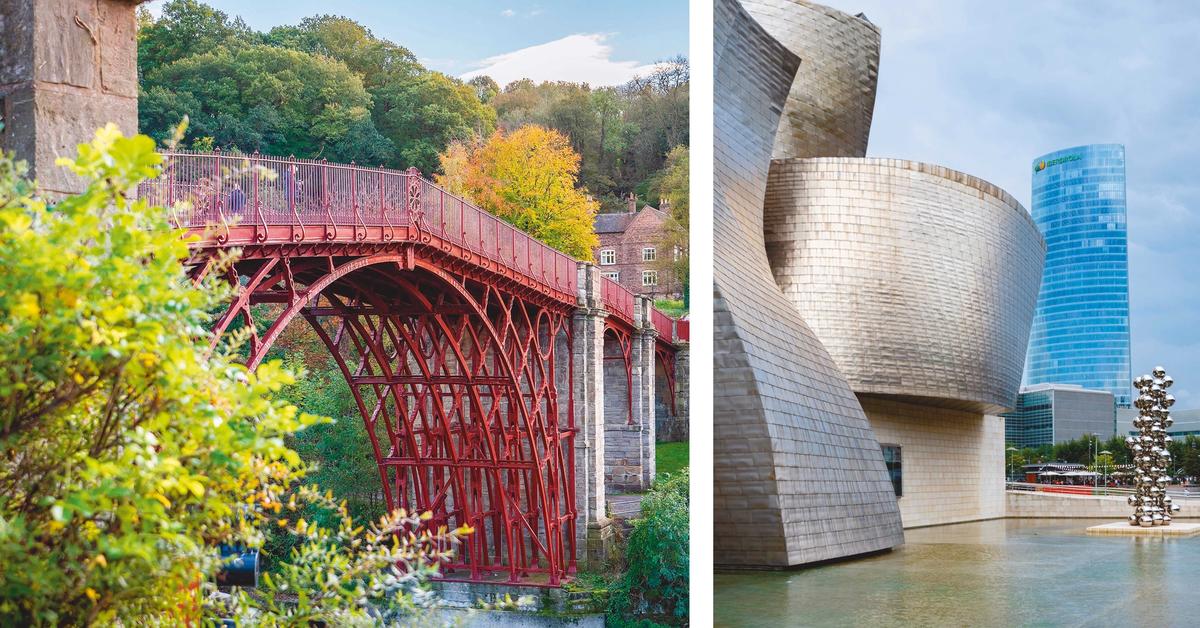

These challenges put the National Lottery heritage money in a more important position than ever, and so we have decided to change our approach. Perhaps the key difference will be for the fund to look for longer-term benefits. Short-term benefits are easily measured, but research by the fund shows that the key issue is long-term viability. One of the largest grants the government gave last year was to the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, which was among the museums hardest hit by the pandemic and subsequent economic aftershocks. Out of a total grant from the Cultural Asset Fund of £9.8m, around £4.5m was set aside to build an endowment to offset future conservation costs and build a secure long-term future for the 35 scheduled ancient monuments and listed buildings in its care.

Just as important as taking a ten- or 20-year view of investment is making sure that it is not just individual projects but whole places that benefit. It used to be thought that investing in a single cultural attraction would transform a place, the so-called “Bilbao effect”, but it is clear that, for people to fully benefit, investment has to be in the whole heritage infrastructure of a place, not just individual museums, galleries and heritage attractions. The fund will intensify its investment in high streets, parks and gardens—indeed whole urban and rural landscapes. To do this, it will need to be more proactive, to encourage projects to come forward that, together, will make a more powerful impact.

A radically simplified process

The recent triumphant reopening of Gainsborough’s House in Sudbury, which the fund supported with a £5.3m grant, is one intervention in the Suffolk market town; 200 yards away is a project by the Churches Conservation Trust converting a redundant medieval church into a cultural centre supported by a £1.9m grant. Together, St Peter’s Church and the Gainsborough museum, and potentially other projects in the town, can transform the quality of a place through its heritage.

To make these changes, and others, the fund will be adopting a radically simplified process and, in future, applications will be assessed on four simple criteria: saving heritage; protecting the environment; inclusion, access and participation; and organisational sustainability. There is a recognition that its current upper funding limit, introduced in 2019, is too low. Applications will now be open for sums up to, and, exceptionally, beyond £10m. But new builds will now be discouraged. The fund will prefer to reuse of old buildings.

Nobody believes that the next few years will be easy for heritage in the UK, but the Heritage Fund hopes that the realignment of its priorities should help give confidence to plan for a long-term future and build the contribution that heritage makes to national life.

• Simon Thurley is chair of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund