Pottery occupies a somewhat uncertain place in the visual arts spectrum, with its long tradition—particularly in the UK—of drab utilitarianism and twee decorousness. The work of Lucie Rie (1902-95), which began in Vienna in the 1920s and continued in Britain in the 1930s after she was forced to flee Nazi persecution, has been instrumental in changing the artistic status of ceramics.

A new exhibition, Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery, which opens at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge this month, is designed to showcase Rie’s status as one of the UK’s leading 20th-century ceramicists. The show, which was at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima) until last month, will travel on to the Holburne Museum in Bath.

“Shifting the language and landscape of pottery in Britain”: Lucie Rie’s Straight sided bowl (1970)

Photo: Maak Contemporary Ceramics

Rie’s presence at Kettle’s Yard is no accident. The gallery occupies a house originally owned by Jim Ede, an early connoisseur who acquired a number of Rie’s works; Mima also holds a significant collection and the two galleries have collaborated to create the show. “Rie is credited with really shifting the language and landscape of pottery in Britain, bringing a creative experimental artistry to it, creating works of extraordinary beauty and energy,” says the co-curator Eliza Spindel.

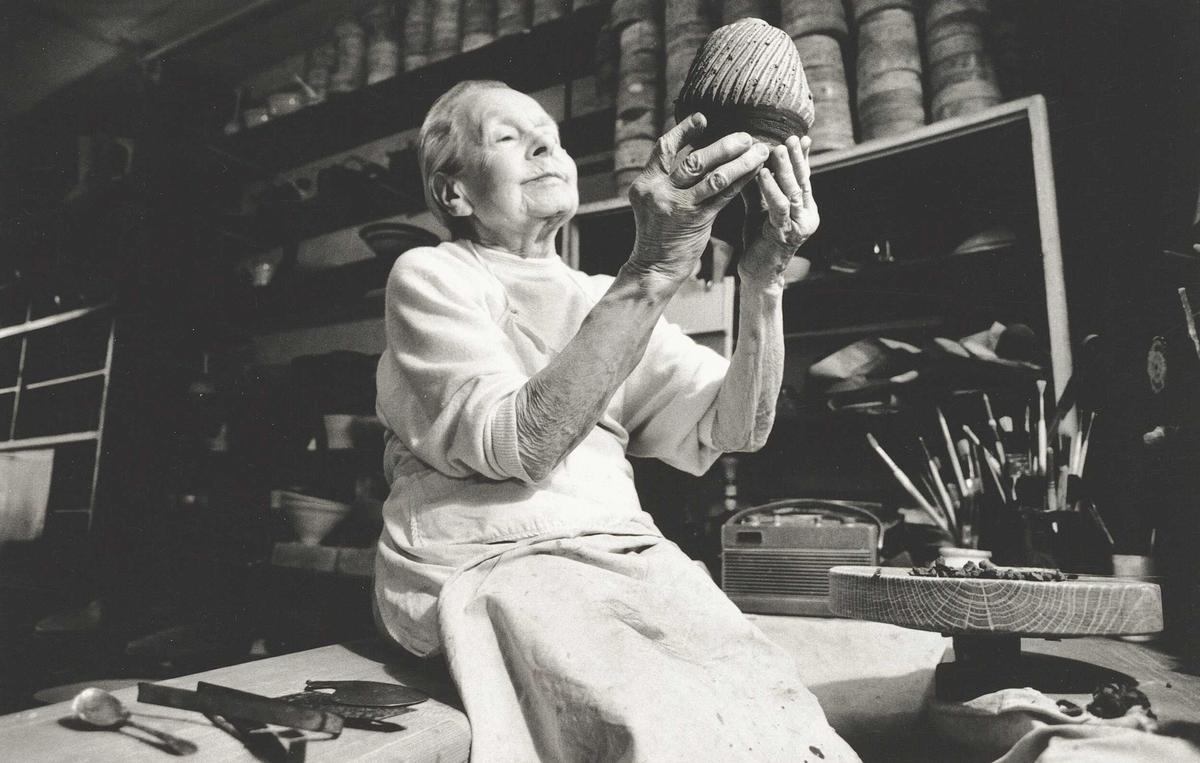

Over seven decades, Rie produced beautifully coloured ceramic pieces that ranged from tableware (such as teapots, bowls and beakers) to more abstract-looking bottles and vases, decorated with a huge variety of glazes and intricate lines of scratched sgraffito. Born to a Jewish family and schooled in Vienna, where she studied under the likes of Oskar Kokoschka, Rie absorbed the revolutionary principles of the period. After Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938, she came to London and set up shop in a small flat-cum-workshop in London’s Bayswater neighbourhood.

A selection of Rie's buttons from the 1940s Courtesy of Mitochu Koeki. Photo: Takao Ōya

Studio pottery was not unknown in Britain in the 1930s, but, as Spindel points out, the UK was “dominated by a trend for a rustic, vernacular, historicist style”, led by the likes of Bernard Leach and Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie. But Rie’s status as an “enemy alien” during the war meant she was unable to sell pots, so she turned to producing buttons for the fashion industry; making the best of a bad situation, it allowed her to experiment with glazes and materials. When the war ended, Rie moved into proper production, making high-end tableware that people could buy from stores like Heal’s in London. “We know they weren’t made just to be looked at, because I found the remnants of tea leaves when I unwrapped some of the tea sets for the show,” Spindel says.

As Rie’s fame grew, her interest evolved towards creating less obviously functional items. “She assimilated and absorbed so many influences, whether it was the bronze-age pottery she’d seen at Avebury, or Viennese Modernist glassware, or a rock surface she’d seen in the natural world,” Spindel says. “Rie never described herself as an artist, but that doesn’t mean that her work shouldn’t be valued and appreciated like painting or sculpture. That’s why her work is so special; you can instantly tell something is by Lucie Rie.”

• Lucie Rie: the Adventure of Pottery, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, 4 March-25 June; Holburne Museum, Bath, 14 July-7 January