In 1976, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) mounted a controversial exhibition of colour photographs by William Eggleston (b.1939). Dubbed “the most hated show of the year” by the New York Times, the exhibition nevertheless established Eggleston’s reputation as the inventor of colour photography, inspiring a generation of artists, writers and filmmakers from Andreas Gursky to Sofia Coppola.

Chosen by Eggleston and John Szarkowski (MoMA’s then director of photography), the 75 photographs on display were selected from a pool of more than 5,000 exposures, made by Eggleston on his travels across the US in the early 1970s. Almost 50 years later, The Outlands—incorporating a foreword by the artist’s son, an essay by the critic Robert Slifkin and a short story by Rachel Kushner—offers a new selection of Eggleston’s pictures from this period. It is an overdue opportunity, in the words of Slifkin, “to appreciate the breadth of Eggleston’s early colour photography and recognise the larger themes and concerns in his work”.

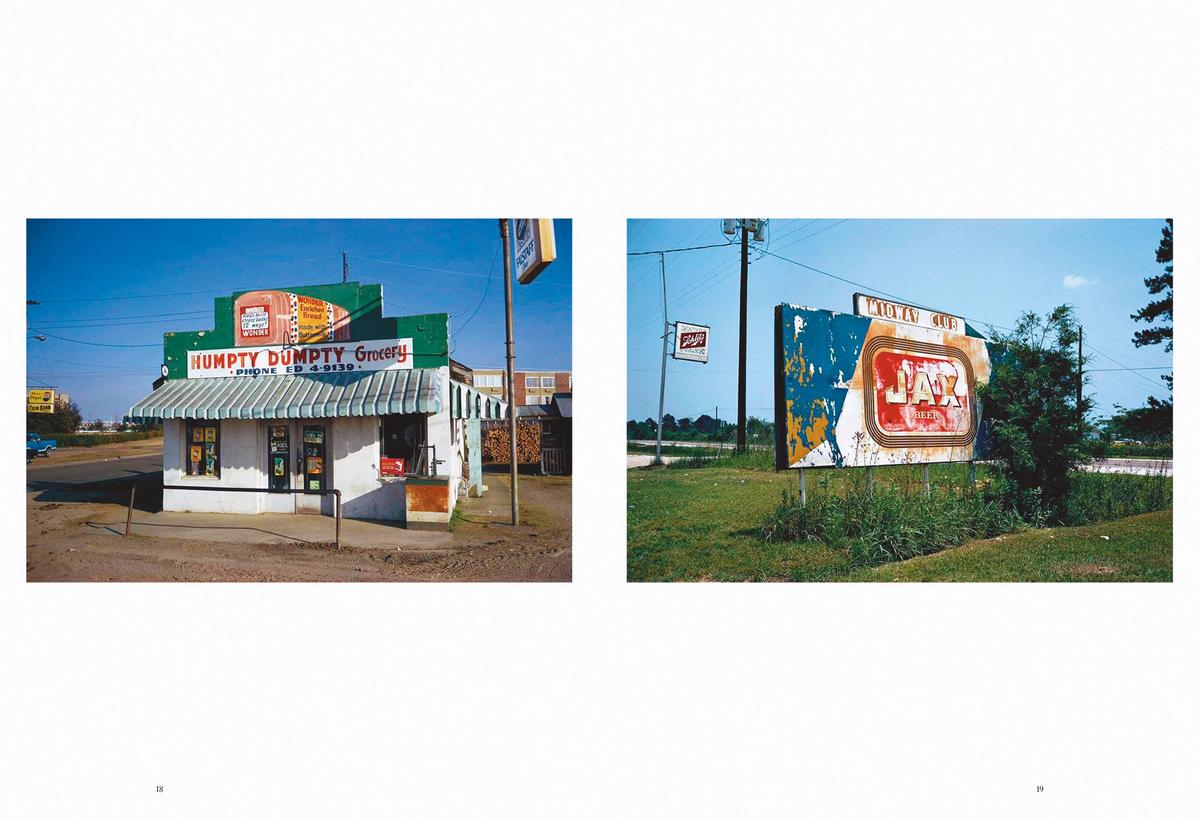

Taken between 1970 and 1973, the 90 images included here reveal the origins of Eggleston’s iconic visual lexicon. The familiar emblems of his work—the gas stations, shop fronts, fast food joints and vehicles of an evolving post-war South—are entirely apparent; early evidence, perhaps, of the artist’s much-cited philosophy: “I had this notion of what I called a democratic way of looking around,” he states in an interview of 2000, a photographic sense “that nothing was more important or less important [than anything else]”. The “democratic forest” of Eggleston’s photography—to borrow the title of his second monograph, published in 1989—yields moments of mundane stillness, even banality; a crate of used tyres, rusted signs, a woman mowing her front lawn on the corner of a street named Standard Drive. Time and again, these photographs arrive with a paradoxical wink: nothing to see here.

William Eggleston’s Untitled (around 1970-73), part of the American photographer’s series The Outlands © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner

Like Edward Hopper, “Eggleston is a master of the glance,” observed Adam D. Weinberg, director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, “capturing those moments, those places, those objects that most others would find unremarkable.” And yet, by lending his attention to the unremarkable and overlooked, Eggleston bears witness to the texture of the everyday, collecting evidence of life lived in the ordinary world. “The magic of a thing you normally see only from a distance disappears when you see it up close,” writes Kushner in “A King Alone”, the short story inspired by The Outlands and included here. “But a new magic takes its place.” Eggleston’s photographs reveal this “new magic”, forcing us to rediscover strangeness in the overly familiar.

Very often, the site of this discovery is the liminal space between urban and pastoral—“intermediary zones”, notes Slifkin, “bearing the traces of human disturbance upon the natural landscape”. Eggleston’s territory is the in-between, part city, part open country, torn between a rural, untamed wilderness and the manufactured landscapes of American commerce. One picture in The Outlands shows a newly opened Shake Shack, its sign a swirl of ice cream reaching skywards like the Statue of Liberty torch. The building is surrounded by dirt, awaiting an asphalt car park. A featureless landscape stretches for miles, its flatness only emphasised by the expansive, cloudy, all-American sky. Elsewhere, Eggleston’s photographs are occupied by dirt roads, tired billboards and semi-developed farmlands; his signature gas stations, of which there are many, are symbols of what goes on between one place and the next.

Because of this, Eggleston’s pictures often project an eerie quality of abandonment. Most are entirely absent of people; those that remain appear to be the last to leave. We encounter trucks rusting at the roadside, faded paint jobs, worn-out signs, vines creeping over buildings and the scaffold of a disused drive-in cinema, rotting like the huge bulk of a shipwreck. More than anything, Eggleston’s photographs reveal the slow, ongoing process of replacement, of one thing succeeded or supplanted by another. In the words of the author Eudora Welty, they “have to do with the quality of our lives in the ongoing world”, capturing “the grain of the present, like the cross-section of a tree”, each ring encased and replaced by the next.

Today, as Slifkin observes, “when color photography has become ubiquitous in all realms of culture”, Eggleston’s steady, patient noticing deserves renewed attention. Both familiar and fresh, these photographs unearth the roots of his career after half a century of burial.

• William Eggleston: The Outlands, Selected Works: Foreword by William Eggleston III, with contributions by Rachel Kushner and Robert Slifkin, David Zwirner Books, 224pp, 123 colour and b/w illustrations, £75/$95 (pb), published 13 October (UK), 6 December (US) 2022

• Rowland Bagnall is a writer and poet, and a PhD candidate in creative writing at the University of Birmingham specialising in North American poetry and poetics