The film-maker Suneil Sanzgiri, who in recent years has gained recognition for a trilogy of films that entwines histories and legacies of colonialism and migrations across the Global South, is the winner of the fourth annual UOVO Prize presented by the Brooklyn Museum. The prize, established and funded by the art storage provider UOVO, recognises the work of emerging Brooklyn-based artists. It includes a $25,000 unrestricted cash grant, a solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum and a public art commission to temporarily revamp the 50-by-50-ft facade of UOVO’s facility in Bushwick. Sanzgiri will present a segment from his first feature-length film in what will be his first solo show. It will debut in tandem with the public commission later this year.

“Using a range of imaging technologies to meditate on what it means to see at a distance, Sanzgiri’s work poetically explores the complexities of diasporic identity, anticolonialism and nationalism,” the museum’s photography curator, Drew Sawyer, who will curate the exhibition, said in a statement. “We’re looking forward to supporting Sanzgiri’s upcoming feature-length film project and sharing his deeply thoughtful practice with our audiences.”

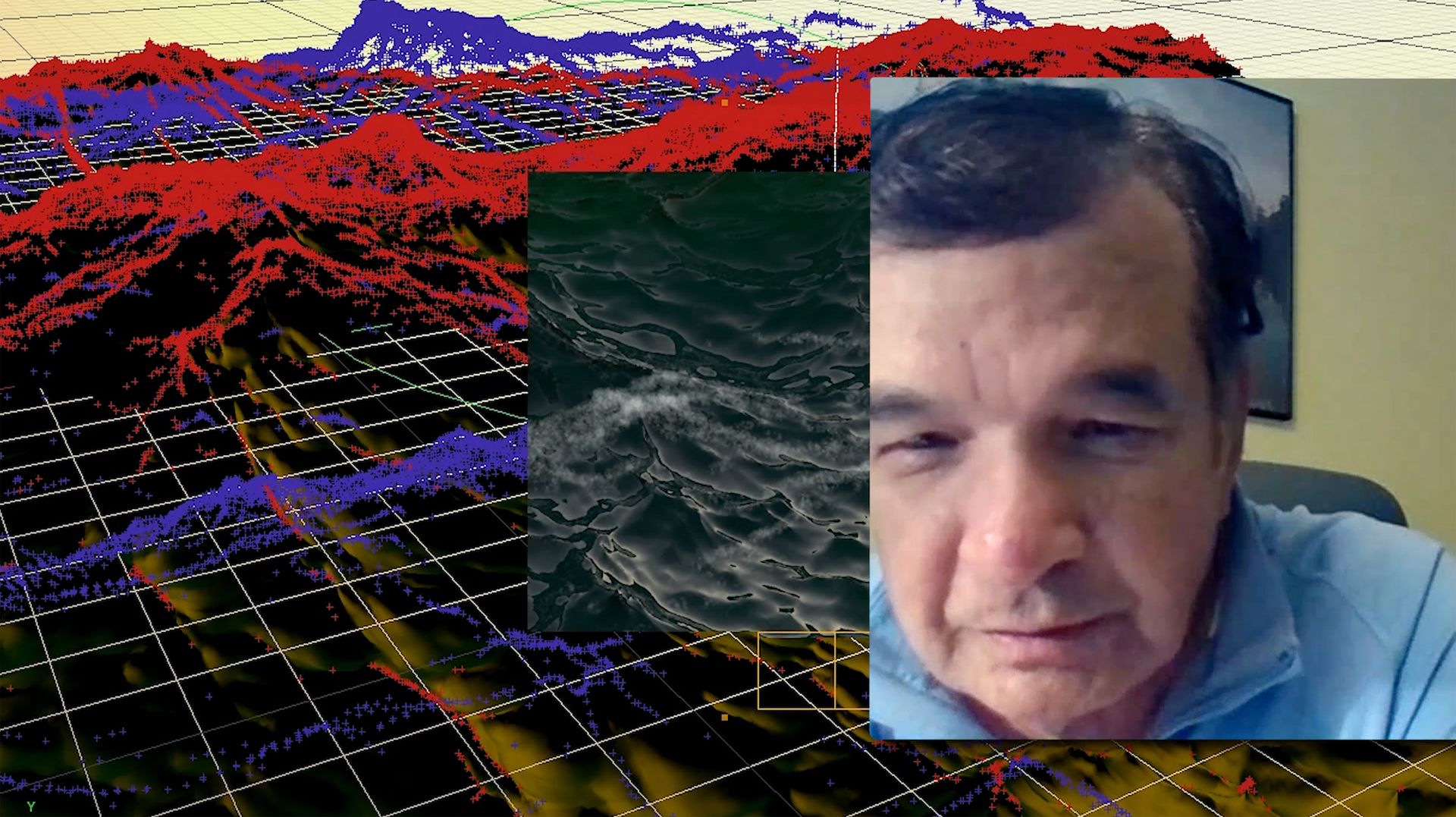

Still from Suneil Sanzgiri's At Home But Not at Home (2019) Courtesy the artist

Sanzgiri is best known for a series of three short films, released between 2019 and 2021, that pull on the threads of the tumultuous history of the Indian state of Goa. Interweaving anti-imperialist revolutionary struggles with the shaping of his own family and identity, they draw on sources from Indian cinema to Portuguese literature to video of present-day conversations with his father. The films seamlessly traverse time and place, and use various media to explore the material and immaterial traces of resistance.

His new feature-length film echoes motifs of the trilogy as it moves across continents, similarly meditating on struggles for freedom through history. A hybrid work of documentary and fiction shot on 16mm film, it integrates such disparate material as footage of Sanzgiri’s ancestral house, mythologies revived as 3D animations and interviews with people including freedom fighters in Goa and the brother of the Angolan revolutionary leader Sita Valles. The tether of the layered work is a woman whose dreams are invaded by the Adamastor, a mythological figure described in the 16th-century Portuguese epic poem Os Lusíadas that attempted to thwart the colonial exploits of Vasco da Gama.

“It slips between the present and the past,” Sanzgiri says. “She’s kind of haunted by this question of what could have been if the Adamastor had prevented Vasco da Gama from ever reaching India. She thinks through various moments in history, and I return to the 1955 Bandung Conference—the Asian-African solidarity meeting—and the possibility of what could have been, as well as the solidarities that developed out of the anticolonial period against the Portuguese between Goa and in different African liberation struggles.”

Still from Suneil Sanzgiri, Golden Jubilee (2021) Courtesy the artist

Sanzgiri’s works have been exhibited primarily in cinema settings, including at the International Film Festival Rotterdam and Hong Kong International Film Festival. The Brooklyn Museum exhibition will allow him to expand his work into a larger physical environment and introduce sculptural aspects to his moving-image practice. In addition to the film, he plans to design a structure for the screen as well as seating that together “reconfigures the viewer’s relationship to the work”, he says. “It’s about positioning these images in a multitiered plane so that there can be different registers for viewers to create their own narratives.” Various ephemera related to his research will also be on view.

For UOVO’s facility in Bushwick, Sanzgiri plans to cover the facade with a 3D-generated image of a bright red banner that reads, “Your history gets in the way of my memory.” The line comes from the poem Farewell by the Kashmiri American poet Agha Shahid Ali, whose poetry has previously seeped into Sanzgiri’s film Letter from Your Far-Off Country (2020). “He’s talking about this idea of history being co-opted, this question of who gets to write history and how does that history differ from the lived experience of others and the legacies of those who came before us,” Sanzgiri says. “I hope that that context is provocative, too, in thinking about our present day, where histories of the transatlantic slave trade and settler-colonialism in the US, works that are trying to grapple with those legacies, are being actively banned.”

Sanzgiri is the first film-maker to win the UOVO Prize; previous winners are John Edmonds, Baseera Khan and Oscar yi Hou. “This is just an exciting opportunity to work at a certain scale,” Sanzgiri says. “It’s such a different experience, to be able to create a work that has a spatial component to it and push myself as an artist into different terrain. I’m really excited for where that journey takes me.”