Christie’s is to auction Head of a Woman (Gordina de Groot) (March-April 1885) in London on 28 February, with an estimate of £1m-£2m. The picture is a revelation, since it has been hidden away in a family collection for 120 years.

Although Van Gogh completed dozens of paintings of heads of peasants in the village of Nuenen in 1884-85, the only sitter whom he named in his letters was Gordina de Groot (1855-1927), who was about to turn 30. At this time he was setting out to paint “heads of the people”, a term he used in English and the title of a series of illustrations in The Graphic, a weekly newspaper published in London. Gordina is also depicted as one of the family gathered for a meal in Van Gogh’s first early masterpiece, The Potato Eaters (April-May 1885).

Vincent’s contacts with Gordina caused a scandal in the village. He complained in a letter to his brother Theo in September 1885 that “this last fortnight I’ve had a great deal of trouble with the reverend gentlemen of the priesthood”, who warned that he “shouldn’t be too familiar with people beneath my station”.

Vincent went on to explain the real problem: “A girl I’d often painted was having a child and they thought it was mine, although it wasn’t me.” He concluded that “knowing the facts of the matter from the girl herself”, the man was a member of the priest’s congregation.

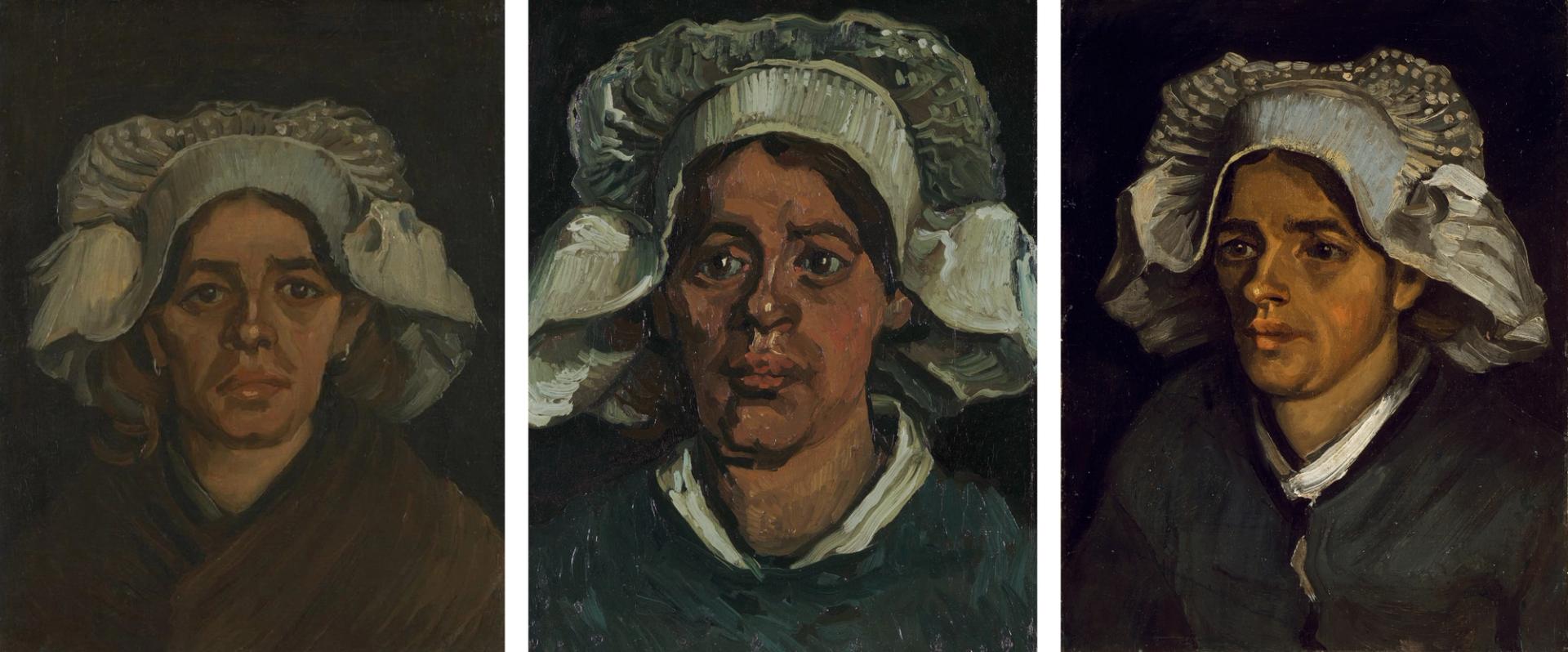

Three other depictions of Gordina de Groot by Van Gogh (around March-April 1885)

Credits: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

On 20 October 1885 Gordina, who was unmarried, had a son, Cornelis. The birth certificate does not name the father. We will never know what happened, but it seems unlikely that Vincent was responsible. He later suggested that the father had been a cousin of Gordina.

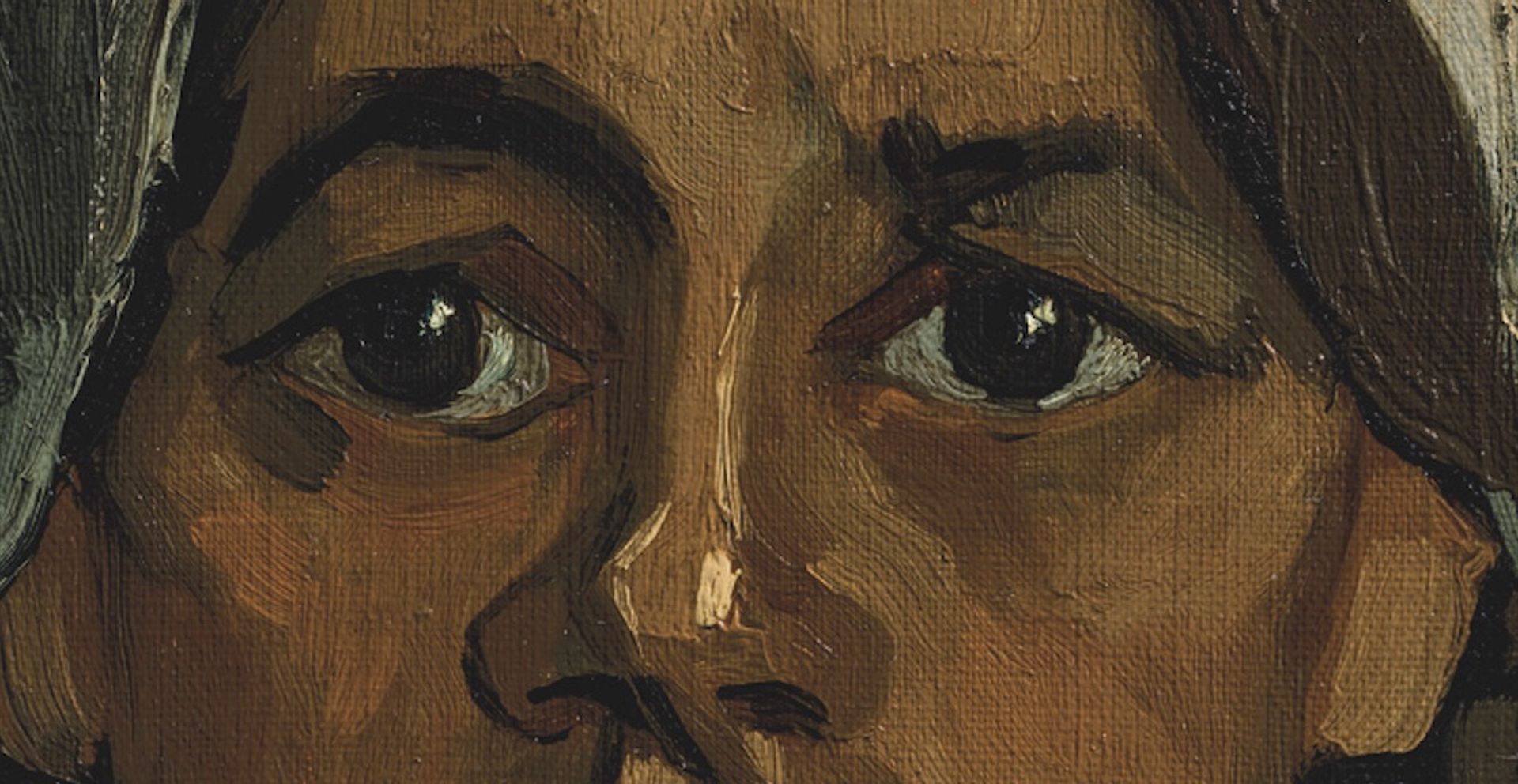

The Christie’s catalogue entry on the painting comments on the accusation: “While he [Van Gogh] vehemently denied these claims, the present work nevertheless suggests a particular tenderness between artist and sitter, evident in the potency of her stare.”

Van Gogh’s Head of a Woman (Gordina de Groot) (detail)

© Christie’s Images Ltd 2023

Head of a Woman was among 40 paintings that Van Gogh left behind when he departed for Antwerp in November 1885. The crate containing his pictures was nearly abandoned, but in 1902 its entire contents were apparently sold by a carpenter for one guilder (less than £1) to a Breda junk dealer. The following year they were acquired by the Rotterdam art dealer Christiaan Oldenzeel, who spotted their potential.

Medal (1936), designed by Johannes Cornelis Wienecke and depicting the banker Henri Daniel Pierson, who had bought Head of a Woman in 1903 Credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In 1903 the Rotterdam dealer sold Head of a Woman to The Hague-based banker Henri Daniel Pierson (1856-1943). Their family bank eventually became part of ABN AMRO, today the third largest Dutch bank. Astonishingly, the Van Gogh work remained for well over a century in the Pierson family and is now being sold by some of the great-grandchildren, who are based in Switzerland. The estimate (£1m-£2m) reflects the fact that Van Gogh’s Dutch paintings do not fetch the enormous sums of his later French works.

The portrait was painted on canvas, but was mounted on a wooden panel before 1903.

Reverse of Van Gogh’s Head of a Woman, showing the wooden backing support for the canvas

© Christie’s Images Ltd 2023

The re-emergence of Head of a Woman will generate considerable excitement among Van Gogh specialists. Its existence had long been virtually unknown, since it was only exhibited once, in Zurich in 1943, during the Second World War. A black-and-white photograph was first published in the 1970 catalogue of Van Gogh’s work by Jacob Baart de la Faille.

The Christie’s sale offers the first opportunity to see the painting published in colour (on the Christie’s website and here) and to view it in London (22-27 February) before the auction. It was also briefly on display in Hong Kong earlier this month, an indication that it could sell to an Asian buyer.

Other Van Gogh news:

Van Gogh: Masterpieces from the Kröller-Müller Museum and An Italian Impressionist in Paris: Giuseppe De Nittis

Credits: Skira, Milan and Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

Two new books are of interest. Van Gogh: Masterpieces from the Kröller-Müller Museum is the English-language edition of the catalogue of an exhibition at Rome’s Palazzo Bonaparte (until 26 March). It will be published on 30 March by Skira.

An Italian Impressionist in Paris: Giuseppe De Nittis, the catalogue of an exhibition which closed this week at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, examines the work of an artist whom Van Gogh admired. In 1875 he made a tiny sketch of a De Nittis painting of London’s Westminster Bridge.