Nam June Paik is often considered the godfather of video. The Korean-born artist took a medium scorned as the “boob tube” and elevated it, eventually seeing institutions study video as an art form. He was too modest to take the credit, but the evidence was there.

In a documentary that premiered last month at the Sundance Film Festival, Nam June Paik: Moon Is the Oldest TV, the artist says, coyly as ever: “I use technology in order to hate it properly.” But he also made it acceptable for others not to hate television. Up until his death in 2006, Paik worked to make television a global community, a continual work in progress. He also filled museums with video creations that reflected his own path from Dadaist “terrorist”, as he was called in his early days, to elder sage.

First-time director Amanda Kim layers her affectionate timeline with archival scenes from the static-filled evolution of a visual medium. It revisits Paik’s journey from Korea to Japan to Germany and finally to the US, and from a life of youthful privilege to one aimed at the killing of sacred cows, and eventually to the refinement of the once-disdained TV. That trip was taken on the internet, which Paik in 1974 called the “electronic superhighway”, coining the term.

TV-era ziggurat: Paik’s largest video tower, The More The Better (1988), at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, Korea National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

Like all machines, the devices he used have been overtaken—by technology, by the marketplace and by users who get younger by the year. Consciously, but mostly unconsciously, later generations are operating in a world that Paik helped bring into being. It is hard to imagine YouTube, the remix or the screensaver without him.

Paik is a natural subject for a documentary, and most of the ground covered in this film should be familiar to those who followed his career. When he arrived in the US in 1958, the Americans who fought a war that ravaged his country still occupied South Korea. Often the only Asian among his American colleagues, his otherness was magnified by his broken German and English, as we hear in the documentary.

A journey in time and tech

Paik was raised under foreign occupation, speaking Japanese. A leftist as a student, he would leave Korea for more than 30 years, making him as much of an exile as he was an immigrant. Politics festered inside of him, surfacing mostly obliquely in his work. He kept critics at bay—when they noticed him—with steely determination under a constant smile.

The documentary follows a straightforward chronology. It cannot help but also be a collage, with footage of Paik’s idol, John Cage, performing in Germany, and pictures of the musically trained Paik destroying pianos. His explanation was that art was best understood when you took it apart. “BC” was Paik’s term for his life before encountering Cage, who would become a mentor.

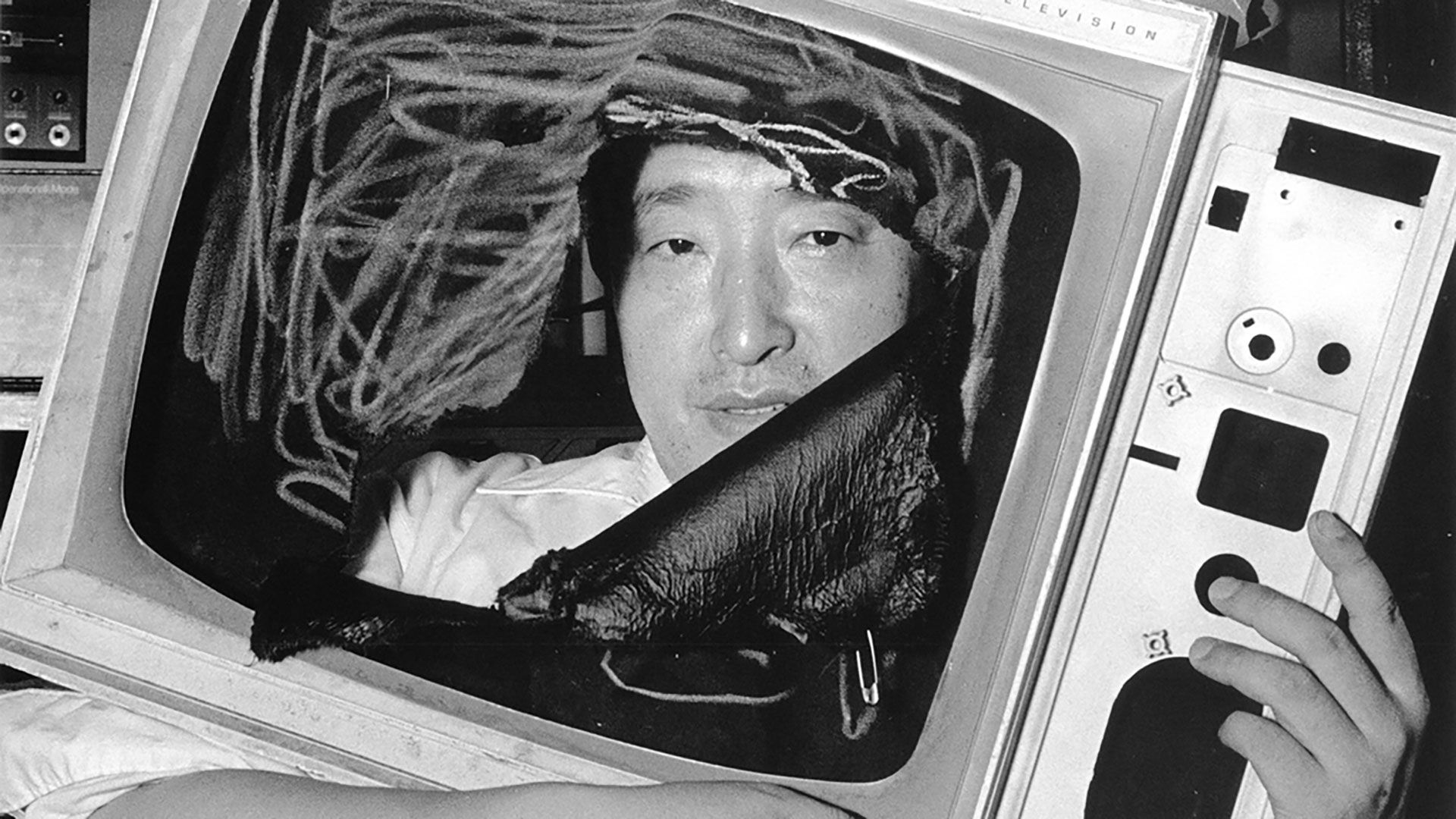

A still from Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV by Amanda Kim Courtesy of Sundance Institute

We watch Paik construct things like handmade robots in an Arte Povera style. Once he seized on video, his oeuvre is documented on tape, from a cross he built with TV monitors in the crossbeams, to a brassiere of two TV screens attached to the cellist Charlotte Moorman. This collaborator was arrested in 1967, along with Paik, when she performed topless on the street.

The film tracks Paik’s rise to visibility through public television events and gallery shows. “I have to make TV as cheap as a Xerox,” he said, predicting that, in a world where everyone has their own channel, “TV Guide will be as thick as the Manhattan telephone book.” The Portapak, a battery-operated recorder, and the digital synthesiser, developed with Shuya Abe, propelled Paik in that direction.

There were bumps on the way. One was the wildly ambitious live global New Year’s telecast of 1984, Good Morning Mr. Orwell, an unintentional farce filled with glitches, miscues and host George Plimpton drunk on champagne. Paik saw the positive side of creating a TV bomb: millions watched.

A stroke in 1996 put the artist in a wheelchair, another machine that needed updating. In his later years, the still-young Paik deepened the Zen-like serenity that was always part of his work. And those images endure. Candle TV, or One Candle, first shown in 1975 and repeated later, was a lit candle inside the empty frame of a television, a reflection on the spiritual in the era of the short attention span. TV Buddha (first made in 1974 and remade for years) placed a seated stone Buddha facing a television showing the figure’s image, a sculptural tape loop.

In Jacob’s Ladder (2000), Paik (with laser specialist Norman Ballard) abandoned the small screen’s scale and created a seven-storey waterfall, with laser projections, in the rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. No one missed the reference to a final journey upward.

There will be more films on Paik as his vast archive continues to be studied. He knew that he and his creations would be overtaken by new devices, like the iPhone, introduced in 2007, a year after his death. This film helps keep us from losing sight of him and his work in the flood of images that he helped set in motion.