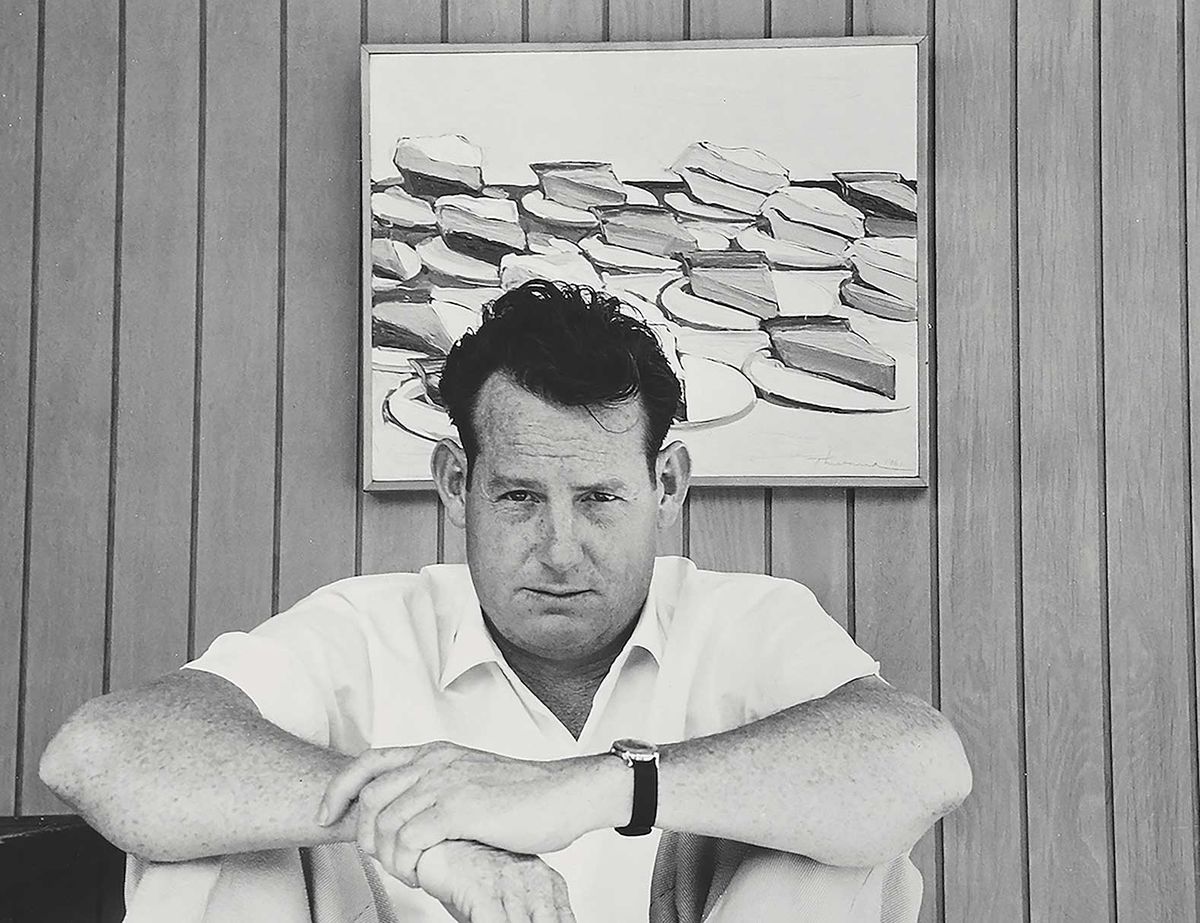

Wayne Thiebaud (1920-2021) never considered himself a Pop artist, but his paintings from the 1960s—vibrant pastel-coloured pictures of pies and cakes, articles of clothing, cosmetics and other humble items—are typical of the movement, their subject matter exemplary of post-war American middle-class life. He went on to paint people in a similarly straightforward style and to adopt a more abstract approach in imaginative landscapes that exaggerate elevation, manipulate perspective and intensify the palette to produce caricatures of the vertiginous topography of San Francisco and the sublime grandeur of the American West.

My god I just painted a bunch of pies. That’s going to be the end of me as a serious painterWayne Thiebaud

Thiebaud, who lived in California, never enjoyed the celebrity of his avant-garde contemporaries in New York. His work was acquired by major US museums and he represented his country at the Bienal de São Paulo in 1967, but only West Coast institutions organised retrospectives (one travelled to the Whitney Museum in 2001), and outside the US he remains barely known. A new survey at the Fondation Beyeler near Basel is only the artist’s second in Europe (until 21 May). Acquavella Galleries has mounted several exhibitions in New York, and the rising market for his work—Four Pinball Machines (1962) sold for more than $19m in 2020—indicates growing recognition for Thiebaud’s oeuvre.

In March 2021, in one of his last interviews, Thiebaud discussed his technique, his work in advertising and commercial art, the Old Masters, the impact of Mormonism on his upbringing, and his philosophy about life itself. The following excerpt recounts a pivotal meeting with Willem de Kooning.

Wayne Thiebaud's Pie Rows (1961) © Wayne Thiebaud Foundation/2022, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo: Matthew Kroening

Jason Edward Kaufman: After your 1956-57 sabbatical in New York, you returned to California and began making straightforward still-lifes, less Abstract-Expressionist and more representational. Did de Kooning really offer you advice that led to the change? Where did you speak with him?

Wayne Thiebaud: In his 10th Street studio. I had been taking students with another instructor from Sacramento on field trips to artists’ studios and museums in New York. I asked de Kooning if he would let us come to his studio. I knew he didn’t want to have anything to do with it, but he was a kind of saint in terms of approachability, just kind and good to every painter. So I had some meetings with de Kooning by myself at his studio.

He was working on his own art and I watched him. Suddenly he jumped up and tore off a piece of newspaper, maybe a comic-strip page. And he looked at the painting, then he pressed this big piece of newspaper onto the upper righthand corner and flattened it out. He came back and sat down. That gave me a lesson on the amazing power of the plane in painting—the invention of collage that establishes planimetric picture-plane power—at which he was so good.

And he gave you some advice?

He said that he thought I was a pretty good painter, but that it lacked any kind of focus in a way which was important. He said, like so many young painters, you’re focusing on what I call “the signs of art”. In other words, someone suddenly becomes famous and everybody looks at what the signs of that particular painter are—brushstrokes, drips, whatever. So, you think, maybe that’s what I should get into my work. He said, that’s not the way to go about it. “Why are you painting anyway?” That was a question which stopped me. I just said, “Well, I love doing it.” He said, that’s not enough. He said, you have to find something you really know something about and that you are really interested in, and just do that. Don’t spend so much time looking at what you think will make you successful.

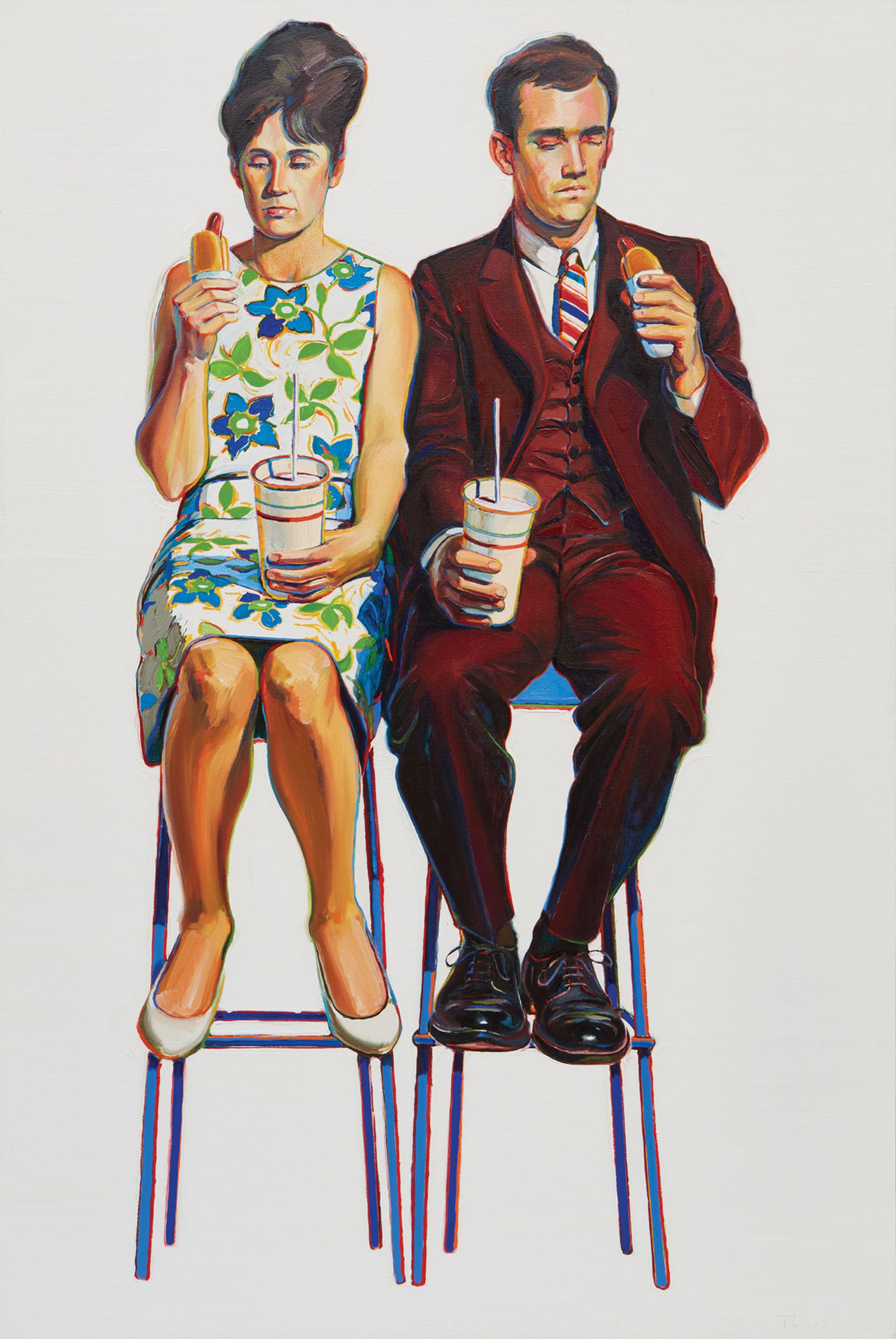

Thiebaud's Eating Figures (Quick Snack) (1963) Private Collection, Courtesy Acquavella Galleries © Wayne Thiebaud Foundation/2022, ProLitteris, Zurich

That was a rude series of thoughts I had not even considered. I was just going along trying anything that might work. And that’s when I came back to Sacramento and sat down and thought about what he said. I said to myself, well, I’ve never been to art school. I know a little bit about art history. What has my life been? I grew up a Mormon boy in America. I worked in restaurants and helped cook hamburgers, washed dishes, was a busboy. What is that world? Is there anything in that world? So I said, I’m going to just start as directly as I can. And I took the canvas and made some ovals, thinking about Cézanne—the cube, the cone and the sphere—and put some triangles over them and thought, well, that maybe could represent a pie on a plate. I had seen them laid out in restaurants and I was always kind of interested in the way in which they formed these nice patterns. I said, alright, I’ll go ahead with this and I’ll make them into pies. I was really enjoying myself… and as I finished, I looked at it, and said, my god I just painted a bunch of pies. That’s going to be the end of me as a serious painter.

But I just could not leave it alone. It was so entrancing. I painted another one of a different kind of pie, and I made some little cakes, and I said, well, I’m out of the art world and in a way, good riddance. Because I had also experienced in New York how desperate all of us young painters were to get our paintings into the art world. I’ve got a teaching job so I'm okay. These [paintings] certainly don’t belong in the art world, so I’m really kind of back to commercial art. I just enjoy doing them and that’s what I’m doing. I’d painted some gumball machines very early on, all tricked up with silver paint like Jackson Pollock. Again, all the signs of art. I decided I’ll just paint a damned gumball machine and that’s the way it’s going to happen. I can’t take a lot of credit for any intellectual insight into it. There were lots of accidents.

• The complete interview appears in Wayne Thiebaud, Ulf Küster (ed), Hatje Cantz Verlag, 160pp, €58 (hb)

• Wayne Thiebaud, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, until 21 May