The attack on Brazil’s seat of government by far-right supporters of the former president Jair Bolsonaro has left some works of art beyond repair. On 8 January thousands of protesters seeking to overturn the inauguration of Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, held just eight days previously, ransacked the congress building, presidential palace and supreme court in the Brazilian capital, Brasília. Two museums in the Oscar Niemeyer-designed complex were also targeted.

Police detained 1,400 protesters and Brazil’s supreme court ordered the arrest of Anderson Torres, Brasilia’s security chief, an ally of the former president, accusing him of collusion with rioters. The court also suspended Ibaneis Rocha, the Brasilia state governor, for 90 days.

Photo: Jefferson Rudy/Agência Senado

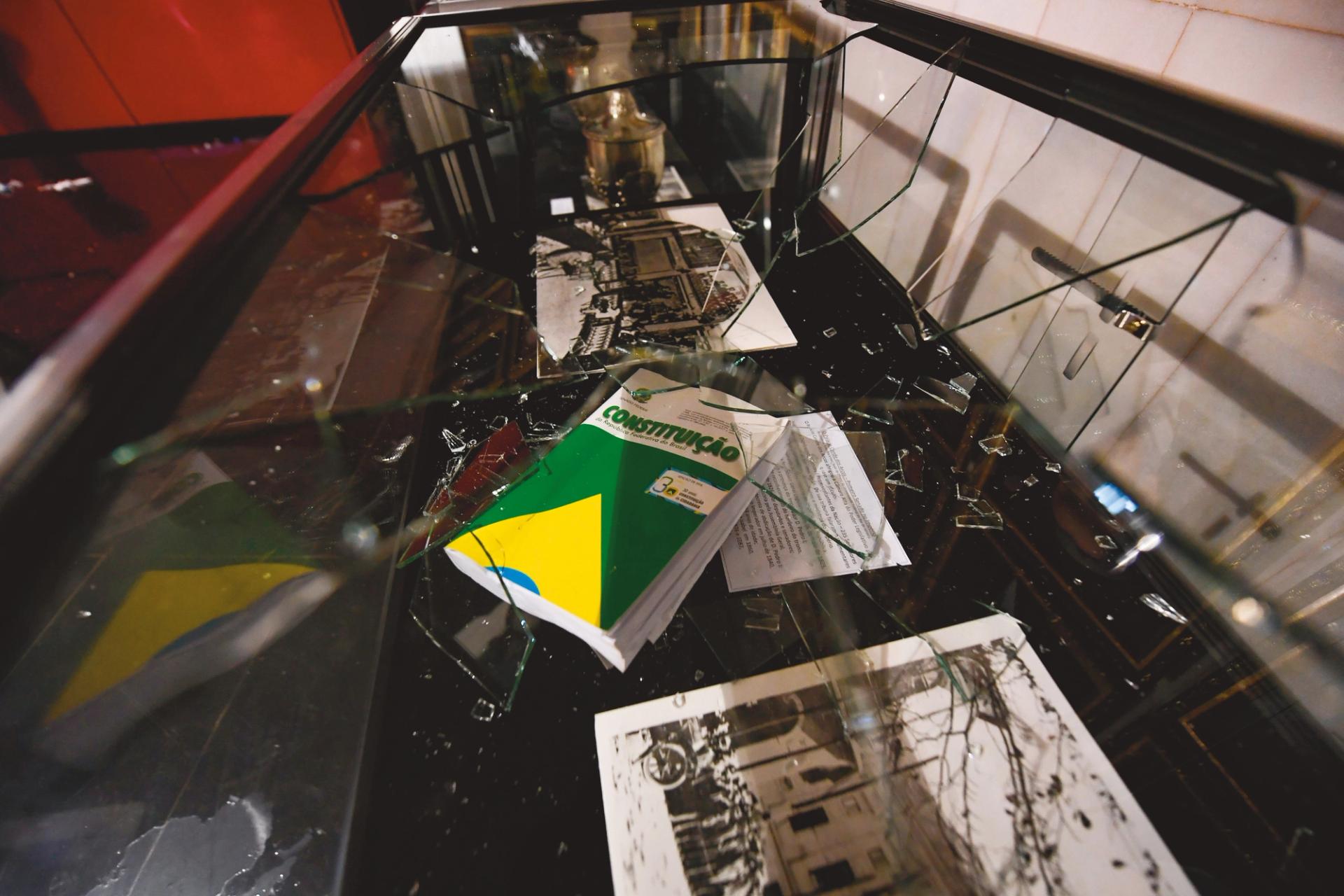

A report by IPHAN (National Historic and Artistic Heritage Institute), the government agency responsible for the preservation of listed buildings, details extensive graffiti, broken windows, smashed furniture and fittings together with arson and water damage.

Bandeira do Brasil (1995), a painting of the Brazilian flag on wood by the contemporary artist Jorge Eduardo, was set on fire and cannot be restored. A 17th-century pendulum clock by Balthazar Martinot is also thought to be irreparable. A gift from the French Court to Dom João VI of the Portuguese royal family in 1808, the clock was, according to IPHAN, left “broken from top to bottom, with numerous cracks, deformation and losses”; photographs show several components, including the face, missing.

I am used to this; it has happened to me before. All my work was against the dictatorship in Argentina—it was often destroyed.Marta Minujín, artist

Canvas ripped with stones

Among the works targeted, in what Lula has described as an attempted coup, was a large-scale canvas fresco, As Mulatas (1962), by the 20th-century painter Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, which was ripped in several places. Two installations by Athos Bulcão, who was part of Niemeyer’s design team, were also damaged, as were hundreds of items of furniture, including in the First Lady’s office.

Photo: Jefferson Rudy/Agência Senado

Fernando Mendes, a spokesperson for the studio of Sergio Rodrigues, says that among the objects by the late Modernist designer to be targeted was a Gordon desk, Vitrine table, Navona armchair, Kiko armchair and Tião chair, all originally commissioned by Niemeyer.

Also damaged was a wooden abstract sculpture by Frans Krajcberg, broken in four places. João Carlos de Oliveira of the Institute of Artistic and Cultural Heritage of Bahia, which manages the Polish-born artist’s estate, questions whether the work should be repaired. “A key feature of fascism is the systematic attack on culture. It is, therefore, symbolic and outrageous—[this] unprecedented level of vandalism committed against symbols of the Brazilian republic,” he says. “I believe the artist would choose to keep his vandalised sculpture as part of a memorial to the events of 8 January.”

The idea of a memorial, featuring some of the damaged work, was mooted by Margareth Menezes, the new minister of culture. At a press conference, Menezes said that while no decision had been made, “a memorial would preserve the memory of the attack, so that violence of this level can never happen again”.

Marta Minujín, an Argentinian artist, said she had no idea her Surrealist bust Vênus Apocalíptica (1983) was in the Brazilian government’s collection until she saw pictures of it dumped at the bottom of the ramp to congress. “It’s a shame, but I am used to this; it has happened to me before,” she says. “All my work was against the dictatorship in Argentina—it was often destroyed.”