For more than three decades, Peter Doig has been drawing on a rich range of sources spanning art history, personal memory, found images and chance associations to make the richly associative, atmospheric works that have established him as one of the most significant and influential painters working today.

But this reputation has been hard won. For most of the 1990s, the Scotland-born, Canada-raised artist’s quietly evocative depictions of snowy landscapes and roadside vistas seemed at odds with the prevailing art world taste for throat-grabbing theatrics and conceptual endgames. But by the end of the decade, and in great part due to Doig’s influence as a tutor at London’s Royal College of Art, young artists were again embracing the power of paint with a vengeance.

I’m still not sure exactly what much of the work is going to be likePeter Doig

Market success followed, and in 2007 Doig became Europe’s most valuable living painter when his White Canoe sold for $11.3m. Art stardom has never been of interest to Doig, who left London in 2002 with his family to live in Trinidad, a setting that infused his paintings for more than two decades. Now Doig is back living in London and his exhibition of new and recent work at the Courtauld Gallery finds him showing alongside many of his Impressionist and Post-Impressionist heroes.

The Art Newspaper: Many factors feed into your paintings, but your physical surroundings are especially important, and your paintings always have a strong sense of place. How has being in London shaped these works that you started in Trinidad?

Peter Doig: When you’re in Trinidad the place is very, very present. Some of the paintings that I started in Trinidad are downtown street scenes. They’re not busy, but they are still street scenes, with façades of buildings and things like that. To remember the atmosphere and get that sense of immediacy, I could always just go and have a look or wander around and feel extremely connected. Now I feel a bit like I’m going back to the way I used to work when I first became known, when I was making all those paintings that were reflecting on Canada. I wouldn’t quite say it’s nostalgia, but it’s definitely about missing something, and also feeling this sudden change. [Trinidad] just feels like it’s so far away. Even doing an interview like this, just prior to the show, is quite unusual because before every other show over the last 20 years I was hidden away in Trinidad and I could just get on with it. So that’s why I’m a bit fraught at the moment, because here we are, just under a month off, and I’m still not sure exactly what much of the work is going to be like.

Do you always work up to the wire?

It’s always been like that, even when I was at college. I love the process, the time in the studio when there’s no deadline. Then I just sort of meander, that’s my nature really. And then, when I actually have to finish work, that’s the difficult thing for me.

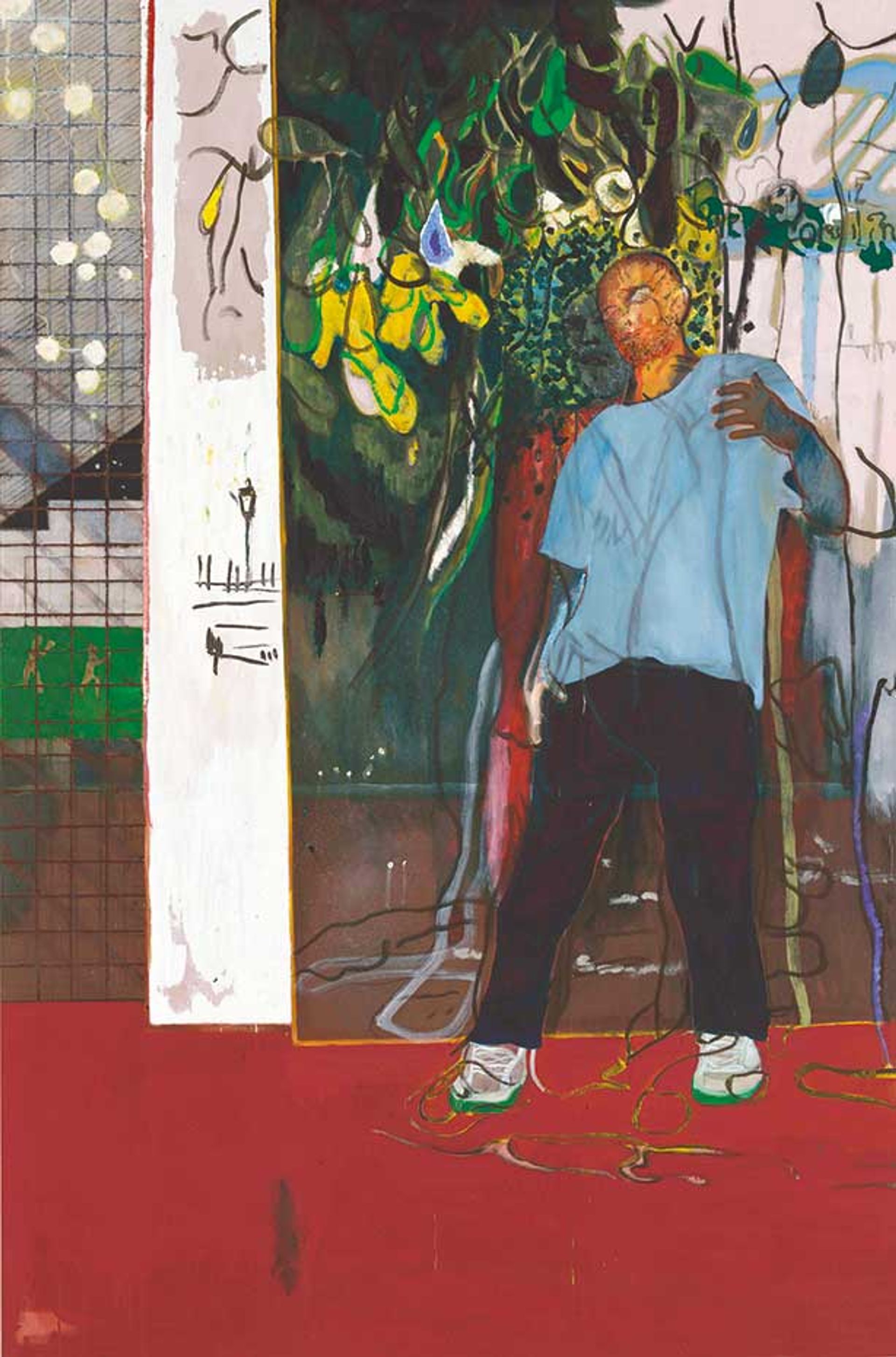

Doig’s 2015 painting Night Studio (STUDIOFILM & RACQUET CLUB) is a self-portrait made when he lived in Trinidad

© Peter Doig. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022

There’s one big new work in the show, a canal scene made entirely in London. I presume it relates to the fact that the Regent’s Canal runs alongside your house?

It started off as a little painting I did for one of my kids, and now it’s big and landscape format and of the canal, which is right outside. But I think it also has to do with looking at the Courtauld [collection]. I thought of the scene as being something that I could imagine one of those Post-Impressionist painters making, and then I was just wondering if I could still make a painting like that, which feels contemporary but also connected to that world of painting.

How do you feel about showing your work in the Courtauld alongside so many of your art history heroes?

One of the main questions was how connected is my work to a collection like the Courtauld, specifically? They were wondering if I could bring the Courtauld into my work. But actually—though I don’t mean to put myself up with those incredible artists or artworks—the Courtauld is already in my work and especially in the great room that you walk through to get to the exhibition spaces. So for me the Courtauld offered excitement about painting of a certain era, and I hope this is reflected in what I’ve made.

I’ve always tried to resist painting figures because I find it so problematic. But that’s also what’s interesting about itPeter Doig

Do you have a long history with the collection?

I used to go quite a bit when I was at Saint Martin’s [School of Art] when [the Courtauld Gallery] was right by the Slade [in Woburn Square]. I remember it was a magical place to go to. There was never anyone in there and you’d see the Gauguins, the Cézannes, the Pissarros. It was special, and not so well known, even though they had probably the most famous Manet painting: A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

Are there any works that you have especially returned to?

I like the Pissarro painting that he made in England of the train [Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich, 1871]. I was thinking a bit about that when I started the new canal painting—it’s the kind of ordinariness of it, even though the Pissarro painting is much emptier than the one I’m making. Then there’s a bather painting that I started in Trinidad: I’ve already done three or four that are based on this photograph of [the US actor] Robert Mitchum, and there was this other one which I wasn’t quite sure about. So I took it back to my studio and reworked it. And now it’s quite different to the Trinidad ones. It’s more connected to—dare I say—looking at Cézanne. Which was part of my reason to take on the subject of bathers in the first place.

Some of Cézanne’s Bather paintings are very peculiar

And often really awkward, but in an interesting way.

Does this awkwardness appeal to you?

Yes, and also just how bad he can be. But bad on an incredible scale and bad in the midst of this whole lifetime of work, so it all becomes part of his evolution. And for me that’s something that’s very exciting about painting: that it’s not just about being exquisite, it’s also about being strange. But I don’t want to get too literal, either. They don’t have a Bather in the Courtauld, but they do have the incredible The Card Players.

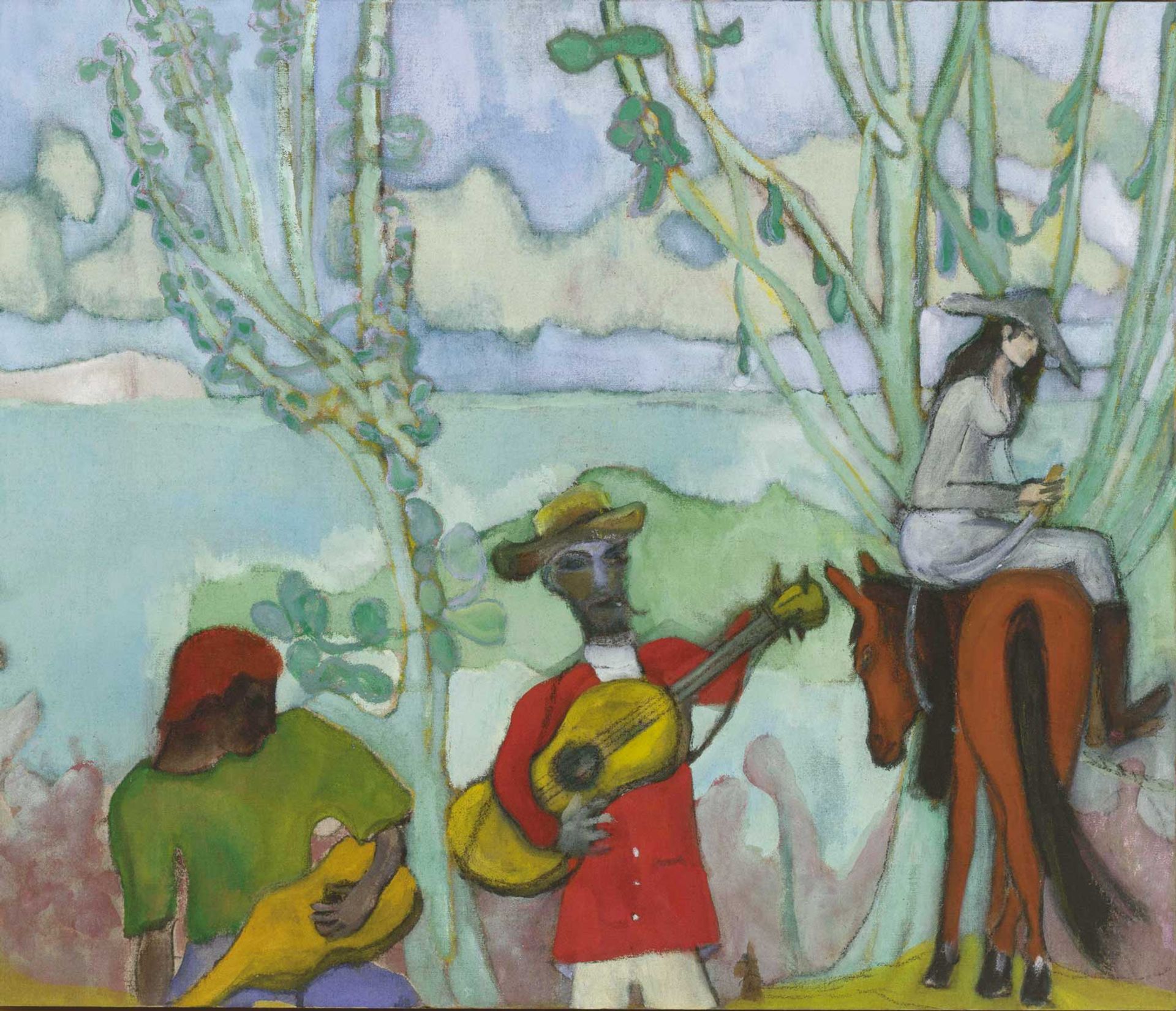

Doig's Music (2 Trees) (2019)

Photo: Mark Woods. © Peter Doig. All rights reserved

Figures seem to be featuring more prominently in your paintings.

I’ve always tried to resist painting figures because I find it so problematic. But that’s also what’s interesting about it and why I want to paint figures. In the new canal painting, there are two figures. The man on a barge I actually saw—youngish, interesting-looking, almost a bit Bill Sykes-like, operating a barge coming out of a tunnel—and then there’s my young son who’s four, who is this big presence of a boy at the front. I have painted some of the kids over the years—it’s my life. But it also comes from thinking about the Matisse painting of the boy and the piano [The Piano Lesson, 1916]. And thinking about how can you make a painting that doesn’t become too sentimental, or whimsical or illustrative. I have this fear, as I think there’s a lot of painting around now that is very illustrative.

You have said that you are fascinated by the way that other artists, and especially figurative ones, use paint in an abstract way.

Cézanne is a case in point. His paintings are figurative but they are also very abstract.

Another component of the Courtauld show is a series of 18 etchings made in response to the poems of the late Nobel Prize-winning Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott. You collaborated in 2016 on the book Morning, Paramin, which contains 50 poems by Walcott in response to 50 of your paintings. How did this come about?

I know his daughters who live in Trinidad and two of my daughters were at school with his granddaughters. But I’d never met Derek. We first met when I went to collect my daughters from the wake after his second wife’s funeral. I was introduced to him and we started talking about painting, because he painted as well, although the writing took over. The day after I met Derek I was flying to New York to meet with this publisher who does books putting together writers with artists, and he was going to put me with another writer. But when I saw him he said, “Change of plan! It’s Derek Walcott!” He’d already spoken to Derek and he wanted to do the book.

So you got to know Walcott through working on Morning, Paramin?

Derek hadn’t seen many of my paintings and a couple of weeks later he came up to meet me at my show in Montreal. He was in a wheelchair. I had only met him before for about half an hour, and there I was pushing him around, this great man, this great thinking brain, this incredible character. That’s the one time I wish I’d had a tape recorder because it was so interesting with all his references. He was also so funny and flippant, but then if he didn’t like a work, he’d just go, “Next!” I had no idea he’d write what he did. It turned out to be his last book.

And now you’ve come full circle by making these etchings inspired by the poems in Morning, Paramin, which Walcott originally wrote in response to your paintings.

Yes. But they are not totally connected to the poems; it’s more like a starting point. And it is still ongoing. I also hope some paintings will come out of this as well. In my London studio I’m putting in a print room, which is a new thing for me. I find so many surprises come out of making etchings, it’s quite alchemical in a way, and paintings can—and do—evolve from them.

Doig's Alpinist (2022) © Peter Doig; ARS

Biography

Born: 1959 Edinburgh

Lives and works: London

Education: 1979-80 Wimbledon School of Art; 1980-83 Saint Martins School of Art; 1989-90 Chelsea College of Art and Design

Key shows: 1998 Whitechapel Gallery, London; 2004 Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; 2008 Tate Britain; 2011 Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; 2014 Fondation Beyeler, Basel; 2015 Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek; Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, Venice; 2017 CAC Malaga; 2019 Secession, Vienna; 2020 National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

• Peter Doig, Courtauld Gallery, London, 10 February-29 May