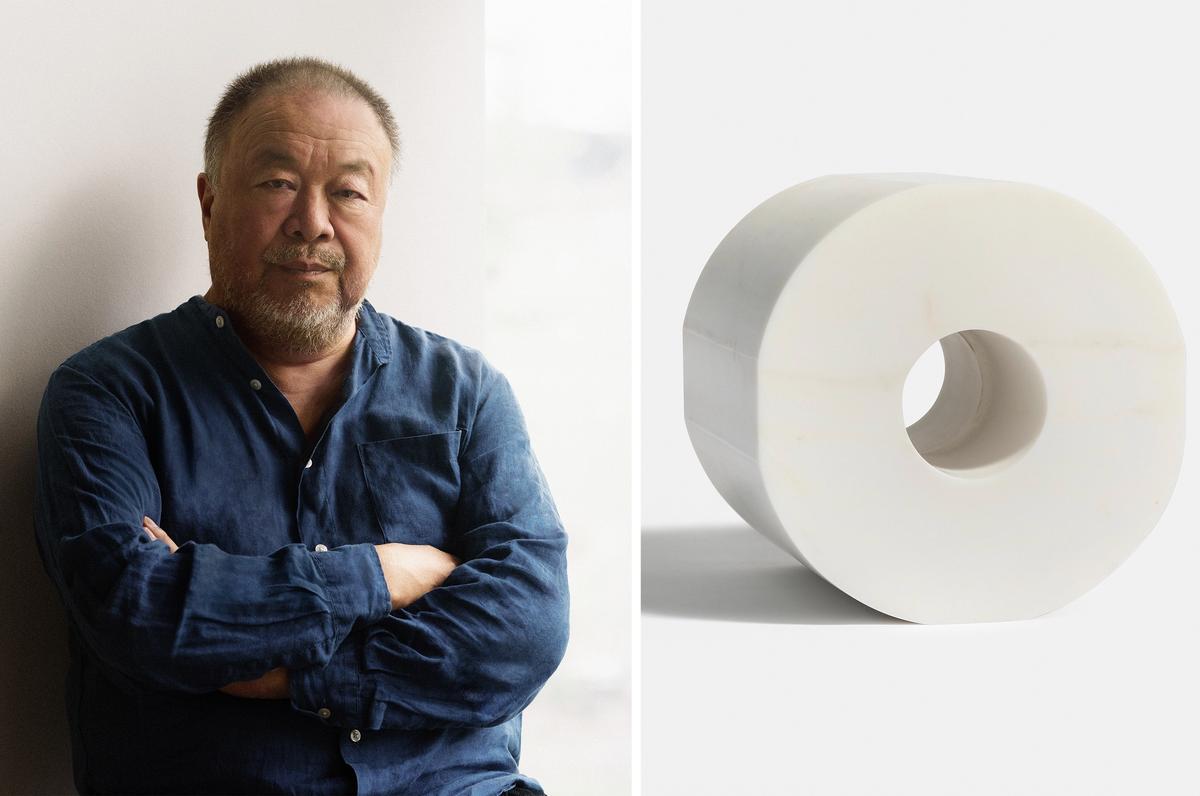

The Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei heads to the Design Museum in London this spring with a major new show unveiling works drawing on the Covid-19 pandemic (Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, 7 April-30 July). Three toilet paper sculptures will go on show—two life-size rolls, one in marble and one in glass—demonstrating the demand for basic disposable products during the coronavirus crisis.

The exhibition—described as the first to frame Ai’s work through the lens of architecture and design—also focuses on the Sichuan earthquake of 2008 and the changing urban face of Beijing over the past three decades.

"[The show includes] things we think of as worthless in ordinary times, something as worthless as a toilet roll, which during the pandemic suddenly became precious… that for him was a real signal of how objects can gain and lose value depending on the context of our times," said Justin McGuirk, the chief curator at the Design Museum and the exhibition curator, at an online press launch. Crucially, “we are not presenting Ai Weiwei as a designer and architect... [but] using his work and his thinking to reflect on design and architecture,” he added.

Untitled (LEGO Incident)

© Image courtesy Ai WeiweiStudio

A number of site-specific installations, comprising hundreds of thousands of objects arranged in sections known as “fields” form the centrepiece of the show. These consist of works collected by Ai in recent year, encompassing items such as Stone Age tools and Lego bricks. The show will also include Ai’s largest work ever made out of Lego.

“This is a show about values; it is a meditation on cultural values and how they shift over time. It presents a history of making over thousands of years,” McGuirk said. “When you collect so much… it tells you about human society,” Ai said at the launch.

One of the “fields”, entitled Left Right Studio Material, includes fragments from Ai’s porcelain sculptures that were destroyed when his Left Right studio complex in Beijing was demolished by the Chinese state in 2018. “They [the pieces] have a moral value,” Ai said. The Lego “field” will display bricks donated to the artist after the company briefly stopped supplying him with material in the wake of his portraits made in Lego of political prisoners.

Another “field” includes almost 2,000 neglected neolithic stone tools which Ai started collecting in the 1990s at places such as flea markets. “Nobody paid attention to them… they [market vendors] were really surprised I wanted them,” Ai said.

Between the 200,000 porcelain spouts from teapots and wine ewers and the 100,000 porcelain balls alongside them, another of the fields shine a light on ancient handcrafted works. “We often say modern people do not know how to wash a dish,” Ai said. “In some senses, we are less understanding… about the touch, texture and shape of forms made by human hands.” The field sections in the exhibition will not be cordoned off to visitors.

Ai Weiwei's Spouts (2015)

© Image courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

The tension between handmade and industrially produced items underpins the show, added McGuirk, highlighting the period of turbulence and transition that China has gone through in the past 30 years. Ai charts the changing face of Beijing following “the tremendous scale of urbanisation and development which brought a lot of destruction, a devaluing of history, a wiping away of streetscapes and architecture”, McGuirk added.

Meanwhile the coffin-like Rebar and case (2012), references the earthquake that devastated Sichuan province in 2008, claiming 70,000 lives. More than 5,000 students were crushed under the rubble of their collapsed school buildings. The new work Nian Nian (2022) consists of 26 prints representing more than 1,000 names handcarved in a jade seal using calligraphy, creating a graphic memorial to the children who died.

Some works will be shown outside the exhibition space including Coloured House, the timber frame of a house that once belonged to a family in Zhejiang province in eastern China during the early Qing dynasty (1644-1911). “The loss of cultural memory is very much one of the themes of this show… Ai is bringing ancient and modern together,” McGuirk said.

• Listen to our in-depth A brush with... podcast interview with Ai Weiwei here