The work of the Italian artist Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) is a rare sight in the UK. He is represented by a single still life at Tate Modern, a second at Norfolk’s Sainsbury Centre, and a small cluster of solitary paintings in Cambridge, Birmingham and Edinburgh. The country’s largest holding of his work is at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. To mark this milestone, Estorick will welcome an exhibition displaying the entire Morandi collection from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation in Italy, which is presented in the UK for the first time.

This unparalleled assembly of Morandi’s work includes rare watercolours, drawings and prints alongside the familiar iconography of the artist’s signature still lifes—calm, understated studies of vases, bottles, pitchers and flowers, all rendered in Morandi’s subtle treatment of domestic light. The show will also tell the story of the artist’s friendship with the founder of the Magnani-Rocca collection, the critic Luigi Magnani (1906-84). Meeting for the first time in 1939, the two men quickly established a significant relationship that would see Magnani acquire 50 of Morandi’s works, the largest presence of a single artist in his personal collection.

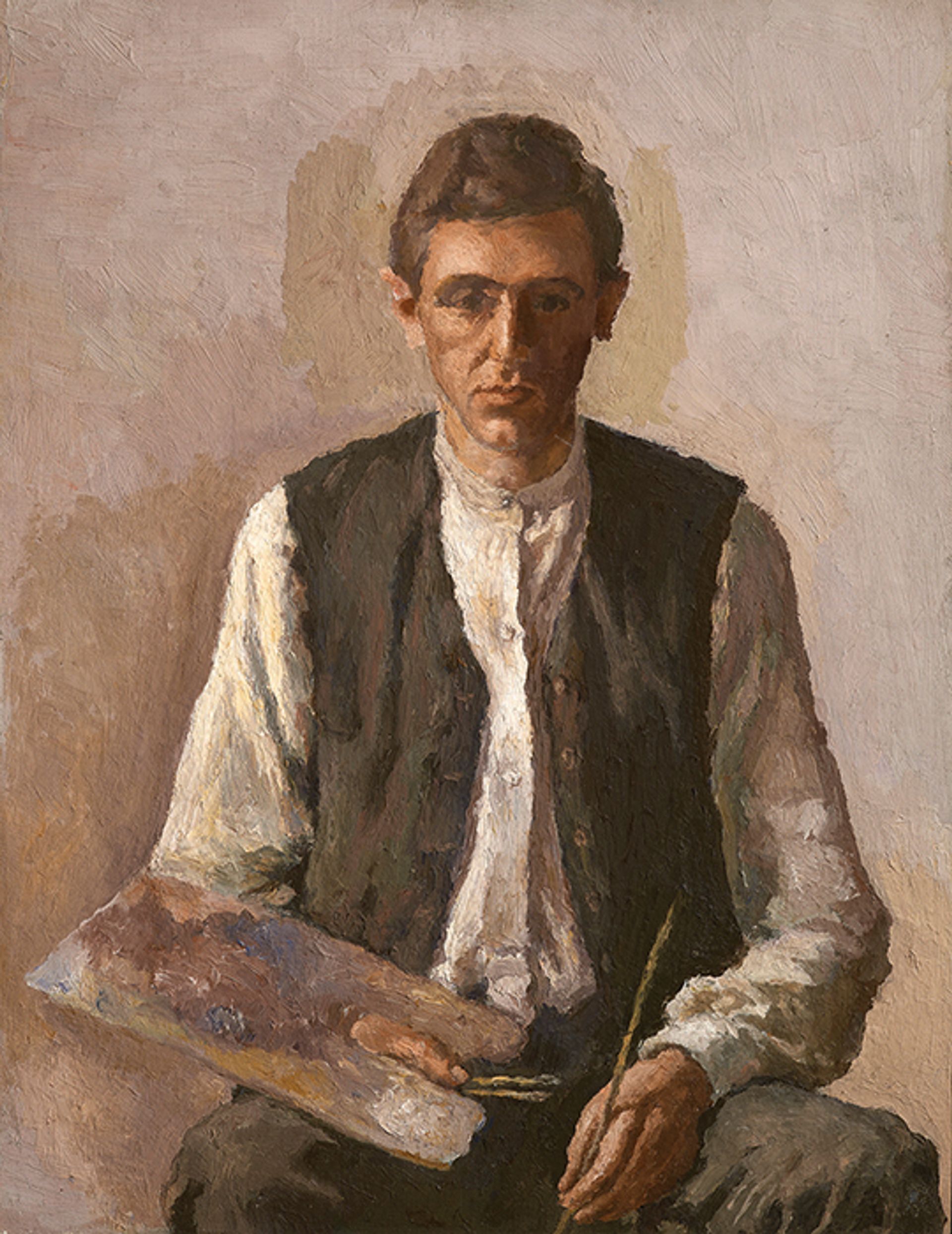

Life in the style of a still life: Giorgio Morandi’s Self Portrait (1925) Photo © DACS; Fondazione Magnani-Rocca

“The collection mirrors their relationship,” says Alice Ensabella, the foundation’s curator for this exhibition. “Magnani never resold a piece by Morandi and many of the works in his collection were a gift from the artist,” revealing something of their “deep and sincere” attachment to one another. “This group of works tells the story of a collection but also of a long-lasting friendship.”

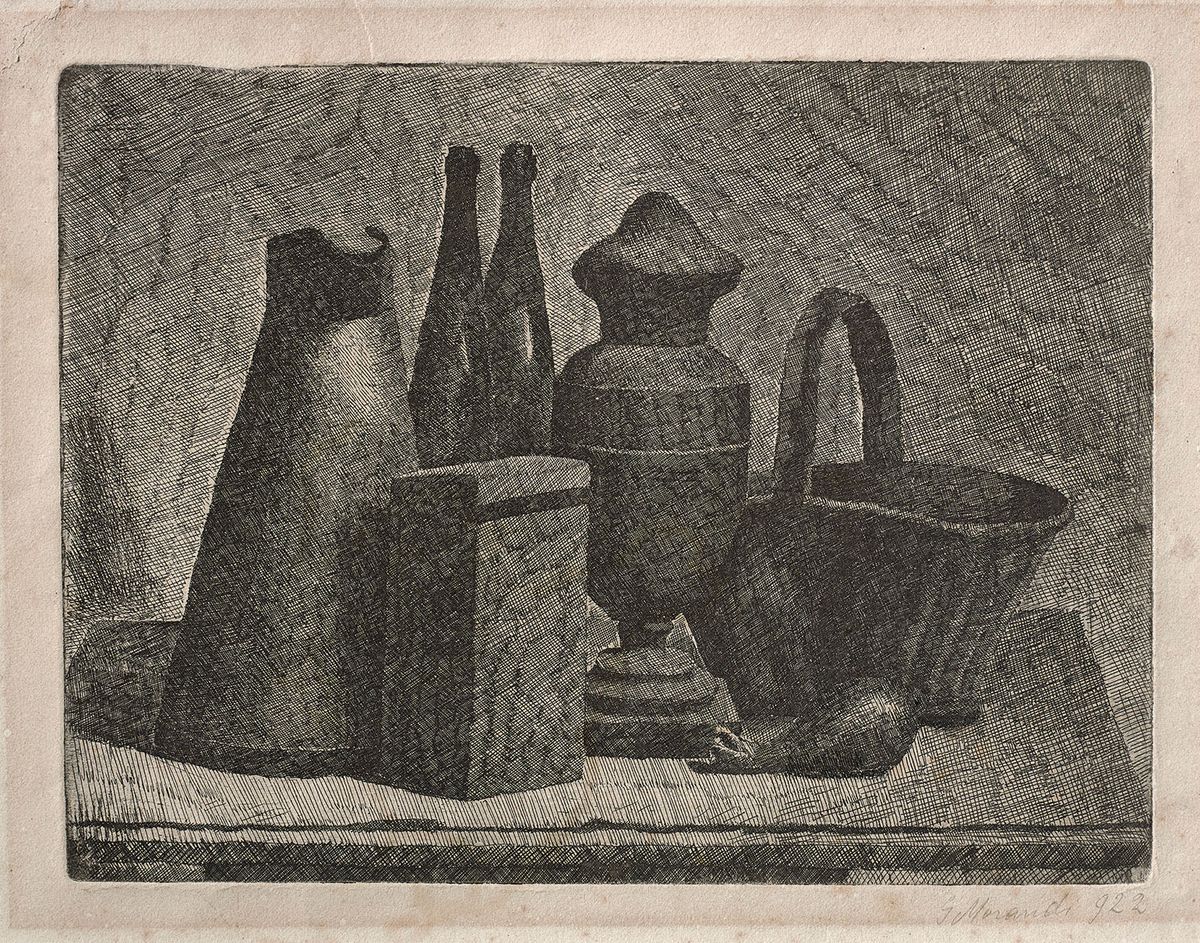

Alongside this story, the exhibition promises to offer insight into Morandi’s lesser-known drawings and prints. Though he taught printmaking for several years at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna, Morandi’s reputation as a printmaker is overshadowed by his painting. This exhibition will enable a new examination of Morandi’s mastery of printed work, further revealing the nuances of tonal variation, space, and the delicate quality of light and shade that have come to characterise his paintings. The exhibition will also bring to Estorick a rare self-portrait, a number of important landscapes, and several distinctive still life paintings including Metaphysical Still Life (1918), a masterpiece of Morandi’s early Metaphysical period, and Still Life with Musical Instrument (1941), the artist’s sole commission.

The timing of this exhibition—“an exquisite coincidence,” Ensabella says—provides an exciting opportunity to consider Morandi’s work in conversation with that of his greatest influence, Paul Cézanne, whose survey at Tate Modern continues until March. “Cézanne is Morandi’s declared model,” Ensabella says. “His work is seminal in Morandi’s formation from the moment he first discovers it in black-and-white reproductions in 1909.”

Considered as a whole, the Magnani-Rocca collection offers a unique survey of Morandi’s career. It shows him to be “like a chess player”, writes Ensabella in the catalogue, meticulously studying “all the possible variations and combinations of his painted objects”. She adds: “A strength emerges in his work to make them universal and out of time, which is why Morandi’s art still fascinates the public.”

• Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London, 6 January-30 April