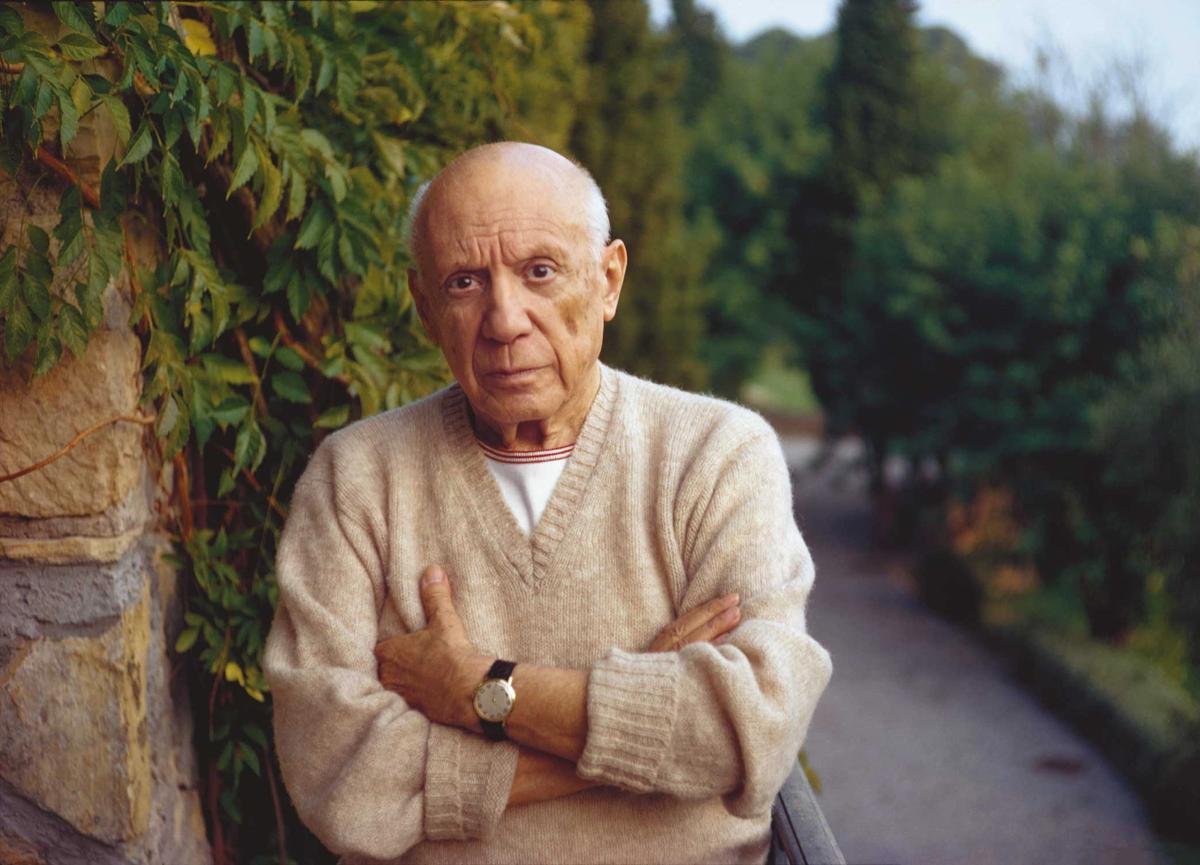

It’s the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death in April. Dozens of exhibitions have been organised under the umbrella Celebration Picasso 1973-2023, while a dedicated Centre for Picasso Studies, formed from the Musée National Picasso-Paris’s library and archives, will also open.

But Picasso’s reputation is arguably in greater flux than at any time since his death. When I interview artists—particularly on our podcast A brush with…—and we turn to the subject of influences, few mention him. Marcel Duchamp, yes. Louise Bourgeois, often. Agnes Martin, too. But rarely Picasso. Compared to a generation or two ago—the 100th anniversary of his birth in 1981, say—this is, I suspect, a huge shift.

It can’t be easily dismissed as art-school orthodoxy. Artists are always drawn to figures far beyond their curriculum. Perhaps Picasso is seen as so squarely a 20th-century figure, and his achievement as so comprehensively mined by previous generations, that he can feel exhausted to artists today.

Then, there’s Picasso the man. The pre-eminence of the late John Richardson, the author of A Life of Picasso (1990), has led to a tendency to centre Picasso’s biography in his art—but that inevitably invites us to see the artist in the light of contemporary values. And while Richardson’s writings on Picasso are dazzling, rollickingly entertaining and rich in detail, they leave little doubt that, as a human, their subject was a monster. One example: in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, his 1999 memoir of his relationship with another Picasso expert, Douglas Cooper, Richardson recalls Picasso sending the pair to visit Dora Maar, the Surrealist photographer who was the artist’s former lover, to see a sketchbook. What he neglected to tell them was that it was dedicated to intimate studies of Maar’s vagina. It was an assignment bent on humiliation and control.

Which is why one of the most fascinating shows in Celebration Picasso, at the Brooklyn Museum in June, seems unlikely to celebrate him at all. Hannah Gadsby, the Australian comedian and art historian, is among the curators. “I hate Picasso,” Gadsby confesses in Nanette, her stage show televised for Netflix. “I know I should be more generous about him too,” she adds, “because he suffered a mental illness… the mental illness of misogyny.” Detailing his behaviour, Gadsby concludes: “That’s it for me, not interested.” Which makes the Brooklyn Museum show all the more intriguing.

It’s a timeless, endless debate, of course. Few have grappled with it better than George Orwell in his brilliant but flawed essay on Salvador Dalí: "One ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously… that Dalí is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being." It feels like it is the right time for fresh views of Picasso, to question orthodoxies, to look anew at his vast oeuvre and his complex life. Some may decry projects like Gadsby’s as cancel culture. But the scale of the anniversary celebrations gives the lie to that. Picasso’s influence and reputation do feel more open to challenge than in the past. But that isn’t ominous; it’s exciting.