During the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Native Americans in the United States and First Nations peoples in Canada suffered some of the highest mortality rates in each country. Especially in cultures structured around community, concepts like lockdowns and isolation ran counter to the ways in which many artists worked—in particular those who have long relied on major indoor fairs and outdoor markets to show and sell their work. From spring 2020 onward, nearly all of the jubilant and sprawling fairs across the American Southwest and other regions were cancelled or held at drastically reduced capacity.

“The pandemic just caused a lot of artists to kind of go inwards, they didn’t have the normal outlets to share their work,” says Douglas Miles, one of many Apachi artists living in a multi-generational household on the San Carlos Apache Nation in Arizona. “But it didn’t stop me at all,” he adds, “it just changed the direction of my art.” For Miles, this meant stepping back from executing tangible projects (he is best known for his murals and his skating brand, Apache Skateboards) and focusing on digital work such as photography, short videos and film projects in collaboration with other Indigenous artists. He even created an online “isolation” studio, a response to Covid-19 in the form of an online viewing room together with Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho artist Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds.

“Native people will always be in tune with the community. We aren’t making art the way white artists are,” Miles says. “We don’t have that luxury.”

Artist, critic and curator America Meredith, a member of the Cherokee Nation and the editor-in-chief of First American Art Magazine, a quarterly publication covering Indigenous art, devoted the publication’s summer 2020 issue to pandemic response. “Immediately people flew into action. It was like, ‘Okay, what can I do in my skills to help the community,’” Meredith says. The encouraging response to the issue led her to put together an online exhibition of masks, with submissions open to all Indigenous artists. She initially expected no more than 20 responses, but upwards of 120 artists submitted work for the exhibition

“In native families, it’s expected that young people assist,” Meredith says. Even so, challenges remain. Meredith recalls two of the most respected elderly Indigenous jewellers that she knows, neither of whom owns a phone or computer. Further complicating issues of connectivity and isolation, many Native American and First Nation communities have notoriously bad internet service, cellular and data access.

In Bluff, Utah, the Navajo artist Thomas Denny relies on selling his work in person but was too afraid to return to in-person events even after restrictions were lifted, well aware of the risk Covid-19 posed for people his age. “I sold one piece in two years,” he says. The Indigenous artist collective Canyon Cow Trading Post, where he sells his work, lost many of its older makers.

“Elders are knowledge keepers,” says Donald Ellis, a leading dealer in the field of historical Indigenous art based in Vancouver. “And when they go, the knowledge often goes with them.” He remembers the panic that swept British Columbia’s Indigenous communities when one of the first people to die from Covid-19 in the province was a highly influential community elder.

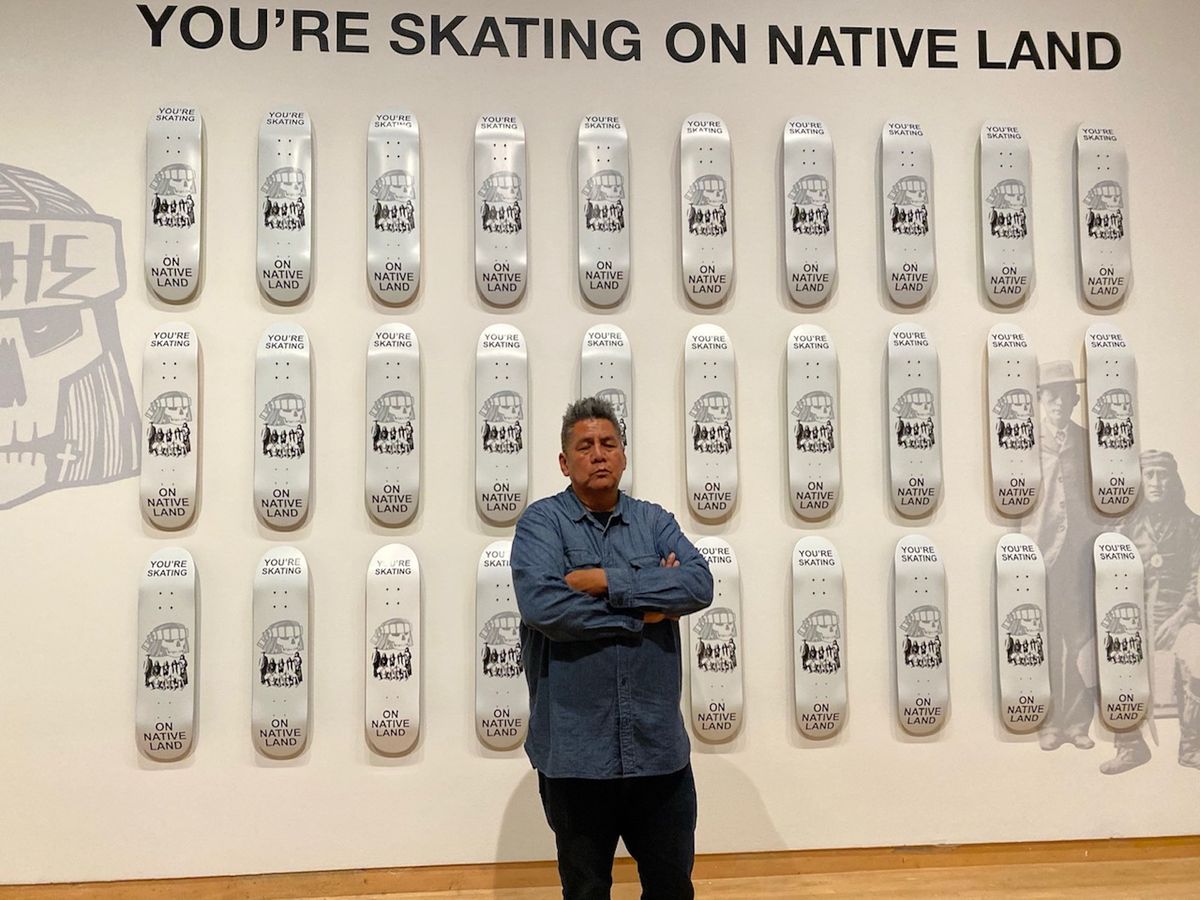

Nicholas Galanin Photo by Merritt Johnson, courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Nicholas Galanin, a prominent Tlingit and Unanga artist whose work focuses on examining American colonisation, says Covid-19 highlighted systemic inequities with a newfound urgency. “Our communities’ access, whether it be food security, housing, healthcare, internet or even clean water all goes into the impact of the pandemic,” he says.

Galanin and Miles are members of a generation of fast-rising Indigenous artists. Both make work that is deeply tied to shedding light on their respective cultural heritages through a “contemporary, cutting-edge lens”, says Ellis. This generational shift is evident not only in the growing number of Native American and First Nation artists represented by major contemporary art galleries in New York and Los Angeles, but also in the increased visibility of contemporary art at the annual Santa Fe Indian Market.

“We saw how truly altruistic Indigenous artists and collectors are” at the height of the pandemic, Meredith says.