Philip Pearlstein, the artist whose realistic, nude portraits breathed new life into figurative painting amidst the rise of non-representational abstraction, died on 17 December at age 98. His death was confirmed by his longtime New York gallerist Betty Cuningham.

Pearlstein was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on 24 May 1924 into a community hit by the Great Depression, during which his father was a vendor of eggs and poultry. In high school, Pearlstein won two national painting competitions sponsored by the publisher Scholastic, and his winning paintings—one depicting a merry-go-round and the other a barbershop, both painted in a style akin to American Realism—were reproduced in Life magazine. He went on to study at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), though in 1943 he was drafted into the war effort. His troupe was stationed in Italy and tasked with illustrating training manuals and painting road signs. This gave Pearlstein an opportunity to travel the country’s major cities and experience work of the Renaissance masters firsthand.

In 1946 he returned to the US and re-enrolled in Carnegie Mellon, where he befriended his classmate Andy Warhol. In 1949, he and Warhol moved to New York City together, sharing an apartment until Pearlstein married Dorothy Cantor, another Carnegie classmate, the following year. Pearlstein and Cantor remained married until Cantor’s death in 2018.

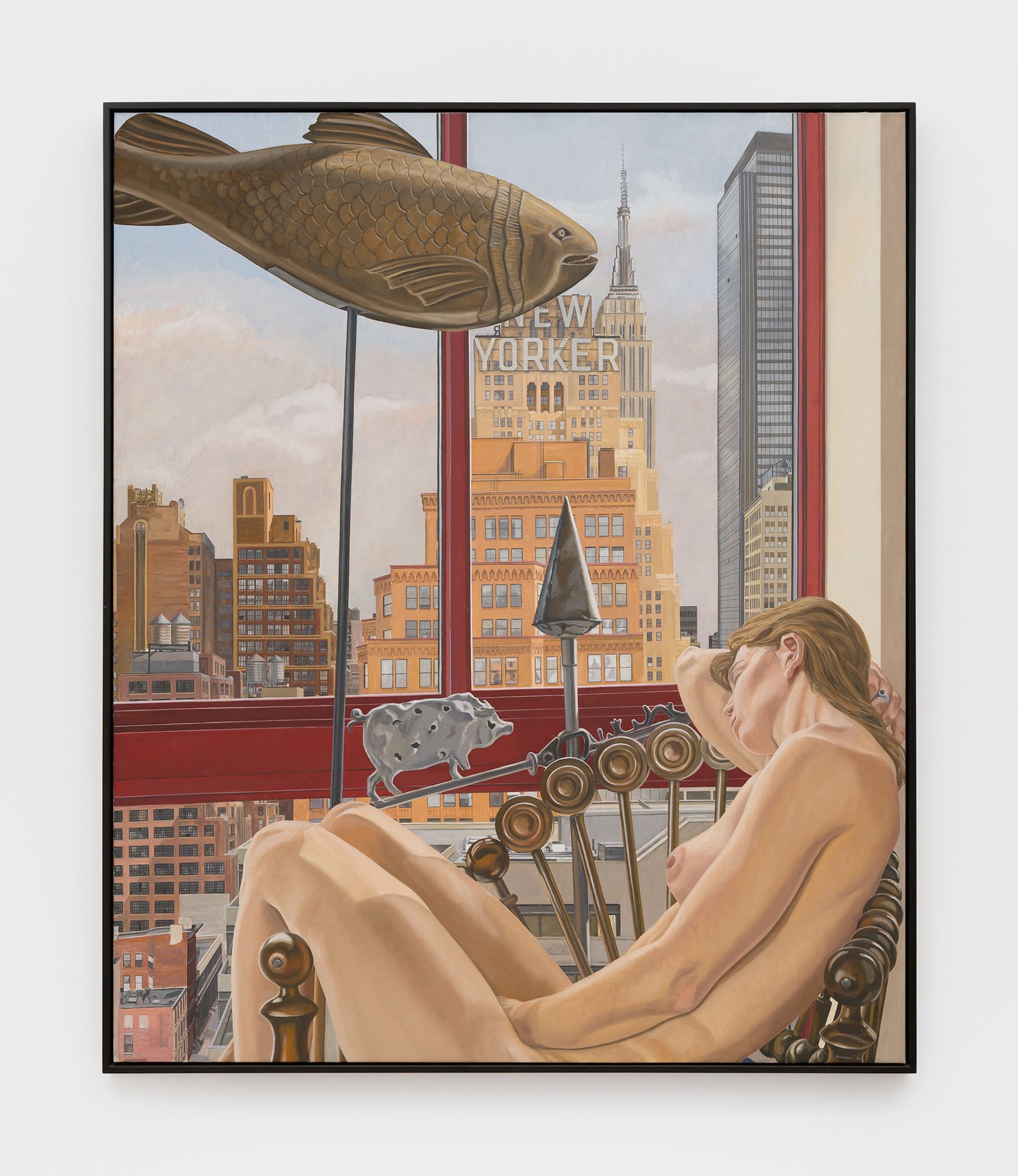

Philip Pearlstein, Model with Empire State Building, 1992 Courtesy Betty Cuningham Gallery

For the first eight years following the move to New York, Pearlstein worked for the Czech graphic designer Ladislav Sutna, designing catalogues for the sale of industrial parts such as plumbing equipment. In addition to earning a master’s degree from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts in 1955—where he wrote a thesis on Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia—Pearlstein also began exhibiting his paintings throughout the city during this period. His work at the time was largely in the Abstract Expressionist style that had recently risen to prominence, a mode of painting from which he would soon break definitively.

In the late 1950s and early 60s, Pearlstein—who was by this time a professor at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn—gained a renewed interest in painting the figure, partly due to a series of figure drawing sessions held in the home of artist and Pratt colleague Mercedes Matter. These figure drawing sessions would often last as long as six hours, and Matter would drape Indian sarees over heaps of pillows and instruct the models to adopt sprawling, informal poses. This sparked Pearlstein’s penchant for strewing the figures about his canvases in informal positions and unorthodox compositions, creating a style he termed “hard realism”. Though the drawing group did not continue to operate exclusively out of Matter’s home, it continued meeting for over a decade and many drawings produced in this group became the reference point for Pearlstein’s paintings throughout the years.

Philip Pearlstein, Nude with Peacock Kimono, 1988 Courtesy Betty Cuningham Gallery

“When I start the paintings I generally forget the actual drawing and start again directly on the canvas, making radical departures, as I see new possibilities just by moving around the posed models, seeing them from other vantage points. The cropping is never planned. It results from the struggle to find the proper scale of the forms within the rectangle. I start to draw somewhere that gives me the most difficult juxtaposition of forms,” he wrote in an artist’s statement published by The Paris Review in 1975. He added: “I rescued the human figure from its tormented, agonised condition given it by the expressionistic artists, and the cubist dissectors and distorter of the figure, and at the other extreme I have rescued it from the pornographers, and their easy exploitation of the figure for its sexual implications. [...] I have presented the figure for itself, allowed it its own dignity as a form among other forms in nature.”

Pearlstein remained committed to this style of work for the rest of his career, though it continued to mature and evolve. A major retrospective organised in 1983 by the Milwaukee Art Museum later traveled to the Brooklyn Museum, and today his work is in dozens of institutional collections around the world, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.