Though many US museums have made public commitments to diversity and inclusion goals, they are still a long way from achieving gender or racial equity in the art they buy and show, according to an exhaustive new data research project. An analysis of almost 350,000 works acquired and nearly 6,000 exhibitions staged at 31 museums across the US between 2008 and 2020 reveals how drastically underrepresented female-identifying and Black American artists remain.

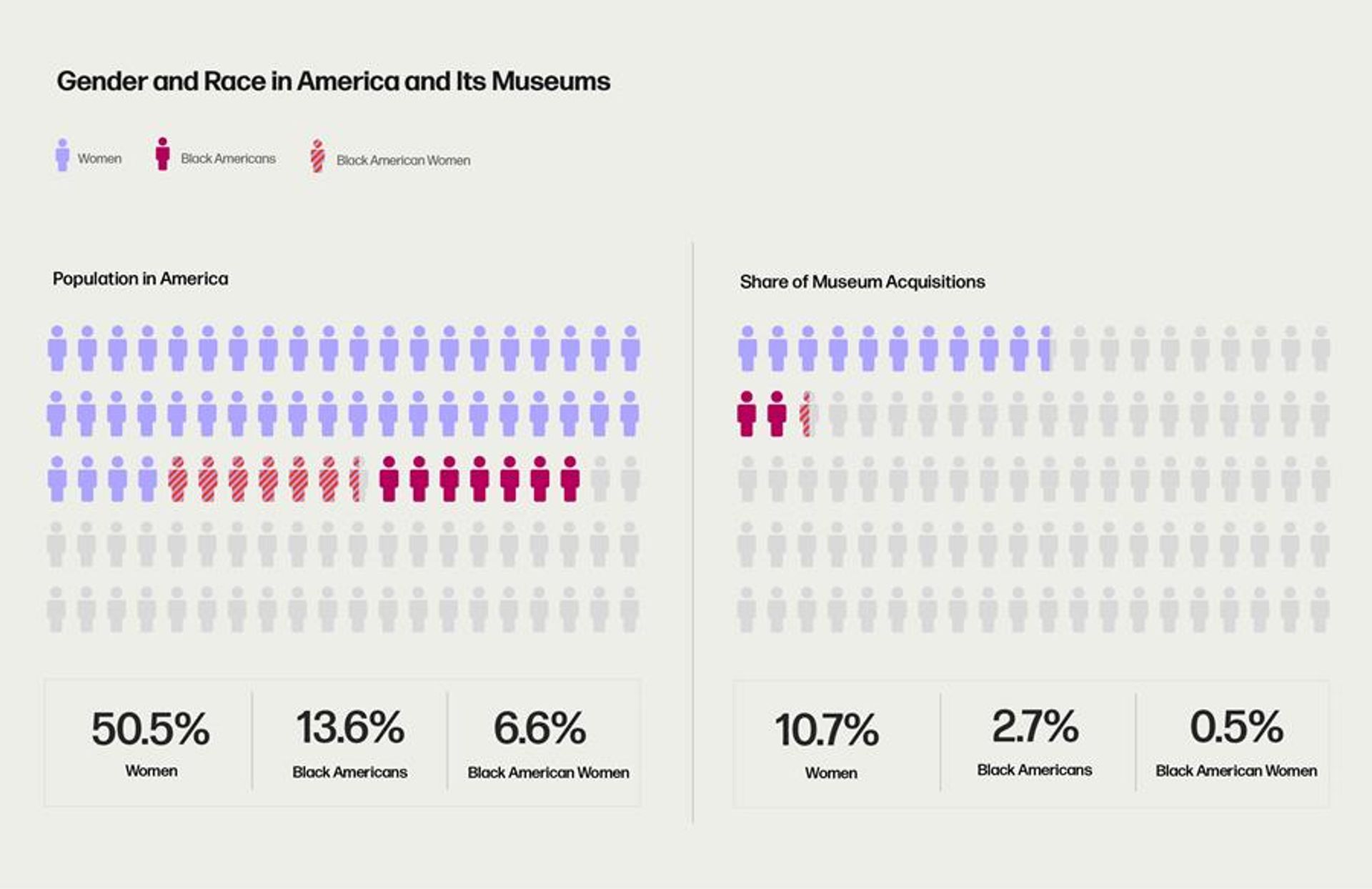

The study, conducted by the journalists Charlotte Burns and Julia Halperin for Artnet News and Studio Burns, found that works by female-identifying artists made up just 11% of acquisitions and 14.9% of solo and group exhibitions during that period. Works by Black American artists accounted for a mere 2.2% of acquisitions and 6.3% of exhibitions. These acquisition figures are roughly one-fifth of “what they should be if collections are to represent the population of the United States”, the authors write in a foreword. The situation is compounded for Black American female artists: comprising 0.5% of museum acquisitions, they are “underrepresented by a factor of 13” compared with the demographics of the US population.

The numbers closely align with the results of Burns and Halperin’s previous surveys of US museum acquisitions and exhibitions in 2018 and 2019. Contrary to popular perceptions that women artists and Black artists are steadily becoming more visible and valued than ever before, the figures from all three datasets document a “real lack of sustained attention” to these groups and “a lack of any kind of systemic change” over the 12-year period, Halperin tells The Art Newspaper.

Graphic by Nehema Kariuki. Courtesy of the Burns Halperin Report 2022

Recent years have seen a flurry of exhibitions telling more inclusive histories of art, and several US museums have deaccessioned works from the white male canon in order to fund more diverse acquisitions. “Our sense of progress is so easily swayed by high-profile, symbolic instances of exhibitions or prices,” Halperin says. “It’s just not a reliable barometer of what’s actually happening beneath the surface.” The survey shows the peak year for museums acquiring works by female-identifying artists was back in 2009, while for Black American artists it was 2015.

Broad cross-section

A broad cross-section of US art museums submitted data for the 2022 study, ranging from smaller regional institutions such as the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in North Carolina and Phoenix Art Museum in Arizona, to contemporary specialists like the Dia Art Foundation and Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, to encyclopaedic giants like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and J. Paul Getty Museum. Nine of the 31 museums participated for the first time, “showing how broadly these trends hold across the country and over time”, Burns and Halperin write. Confronted with the evidence, however, museum officials expressed surprise and even some scepticism at the previous reports, Halperin says.

The data comes less as a surprise than a vindication for Susan Fisher Sterling, the director of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. Founded in the 1980s by the private collectors Wilhelmina and Wallace Holladay, it is billed as a first-of-its-kind museum dedicated to championing women artists past and present. “While we know that there’s been increased lip service to gender equity and racial equity in the art world, the relatively stagnant statistics are not a surprise,” Fisher Sterling says. “The counting is still really important. Because until you put that into people’s mindset, until they see the numbers, we all want to believe that we’re better than we are.”

Museums are responsible in part for shaping the supremely white and supremely male art-historical canonLiz Munsell, Jewish Museum

“I’m disheartened that we’re still not making as much progress as we should be,” says the curator Marissa Del Toro. As a team member of the research and advocacy initiative Museums Moving Forward (MMF), Del Toro contributed to cataloguing some of the data for the Burns Halperin report. “Conversations about inclusivity within museum collections have been happening since the 1970s,” she points out, citing the artist Howardena Pindell’s 1987 investigation of institutional racism in the New York art scene and the critic Maurice Berger’s 1990 essay, “Are Art Museums Racist?”.

“Museums are responsible in part for shaping the supremely white and supremely male art-historical canon that we have today—but they can also be part of the solution,” says Liz Munsell, a contemporary art curator at the Jewish Museum in New York and fellow team member of MMF. After “decades of exclusion”, it may take decades of targeted acquisitions to build collections that reach “any level of equity”, she says. “But that, I believe, is the intention of many of my colleagues in the field”.

Despite the dismal overall picture, the report's data does suggest that museums are beginning to direct their acquisition budgets towards women artists. Purchases of works by women—as opposed to gifts—peaked in 2019, implying it has recently become a priority. And purchases of work by Black American female artists outweighed gifts by 56% to 44%. “When institutions have their own money to spend, they’re spending it differently from their donors,” Halperin says.

The report also indicates much greater diversity in the collecting practices of contemporary art museums. On average, their acquisitions during the 12-year period comprised 48.2% work by female-identifying artists and 8.8% work by Black American artists, which combined to reach 3% of work by Black American women artists. Dia topped the survey for acquiring works by women artists at a rate of above 62.5%, thanks to the leadership of Jessica Morgan, who became director in 2015. The Pérez Art Museum Miami (Pamm) and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago are among the leading collectors of work by Black American artists—a category in which museums with mid-sized budgets of between $15m and $20m “outperformed their peers”, note Burns and Halperin.

All about commitment

While many US encyclopaedic collections were formed in the colonial context of the late 1800s, Miami’s museum boom a century later means “a lot more women and a lot more artists of colour than in other places”, says Pamm’s director, Franklin Sirmans. “We can be more reflective of what is important to people in the here and now.” The museum has an endowment fund for acquisitions of Black diaspora art, established in 2013 with a $1m gift from museum patron Jorge Pérez and the Knight Foundation, as well as donor groups that support exhibitions and programmes featuring international women artists and Latin American and Latinx artists. “It’s not just about the money, it’s about the people,” Sirmans says. “Of course, it’s not a representation of everyone in the community, but there are vocal folks in each one of those groups.”

“It’s going to be a lot more difficult for encyclopaedic institutions to catch up,” Halperin admits. Yet, more than the size of a museum’s budget or its collecting focus, the report suggests that “the major distinguishing factor for museums that make progress is that they commit”, she says. “Buying something by definition means you’re not buying something else. The ones who have made progress have been willing to set themselves goals rather than just operating on a ‘what is available?’ basis.”