It was an afternoon in late August 2019 when the poet and art critic Peter Schjeldahl first got the call from his doctor with the news that his lung cancer had spread. He was driving to meet his wife, Brooke, at their country house at Bovina, in the Catskills. Patsy Cline’s Walkin’ After Midnight played on the car radio and Schjeldahl had just hit mile 81 of the New York State Thruway. The emerging mountains reminded him of a revelatory Thomas Cole painting; the hills spread out before him, and he reflected on the history of how long painters had painted these mountains. Schjeldahl recounts the moment in “The Art of Dying” (The New Yorker, 2019), a long-form essay and critical road trip through his life in art, in which he characteristically discovers the emerging possibilities of painting in the most unlikely places. He was an indispensable art critic who wrote with the lyric observations of a poet.

Schjeldahl’s direct and unflinching prose made an enemy of complacent or proudly dissatisfied art writing that had little personal use for art. A respected poet as well as a critic, he was a lifelong enthusiast for painting, for New York, and for the reparative possibilities of art during times of personal and collective crisis. “I’ve never kept a diary or a journal, because I get spooked by addressing no one,” he wrote, “When I write, it’s to connect.” Despite the anguish of living with a terminal illness, his body playing host, in his own words, “to a gang war between the immunotherapy and the cancer, with both living off the land”, he continued to write fluent and eloquent criticism throughout his final summer.

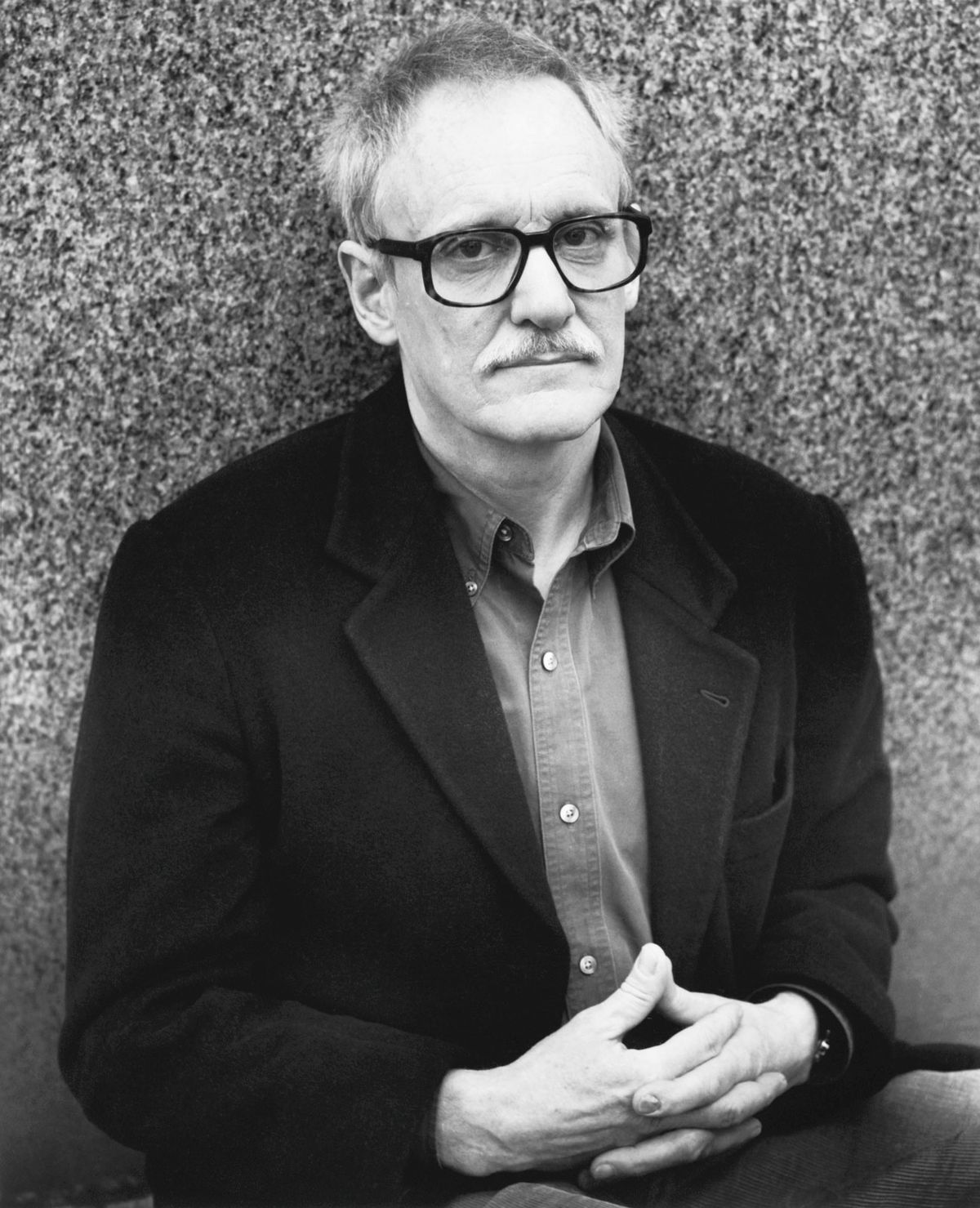

At the time of his death, Schjeldahl was 80 and the long-time art critic at The New Yorker, which he originally joined as a staff writer in 1998. Commanding an unmistakable critical voice, which often blended wry humour with forensic observations on the play of pigment and line, Schjeldahl’s art writing appeared in Artforum, Art in America, the New York Times Magazine and Vogue. It was produced over 50 or so years in the same study of his top-floor East Village walk-up apartment. But despite the glossy glamour of these serious and middlebrow magazines, he always wrote about New York with the verve of an outsider, a master navigator of what today we might call the high/low in cultural production.

Schjeldahl grew up in the snow-flecked grey of the Midwest. Born in Fargo, North Dakota, he was the oldest of five raised by a “prairie princess” mother, Charlene, and a working-class hero father, Gilmore, in provincial Minnesota. The patented inventions that made Schjeldahl’s father moderately successful—a widely rolled-out airsickness plastic bag, and then the NASA Echo 1 and Echo 2 Mylar-balloon satellites—led to his son being regarded as “the rich kid” when he smoked cigarettes as a 16-year-old behind the high-school football bleachers in Northfield, Minnesota.

The family gathered every week to watch The Ed Sullivan Show, including one time in 1956 when Elvis Presley came on and changed everything. It’s easy to see how early experiences like these marked so much of the prose that came after. First, Schjeldahl felt the double-bind of every smalltown kid who manages to get out: the gentle contempt for anyone who does not want to live their life at the teeming centre of things, mixed with finding himself in art by understanding what life is like for those underprivileged who do not speak International Art English outside the cliquish citadels of blue-chip galleries. It is a rare double qualification today. In “Andy Warhol”, for instance, the first collected essay in the infuriatingly readable Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light: 100 Art Writings 1988-2018 (2019), he celebrates Warhol not as a perverse ironist, but as a working-class boy who had the imagination to take “the format of Barnett Newman and put Elvis Presley on the front”.

Mixing confidence and self-deprecation, Schjedldahl said that the “only thing that I am a world expert in is my own experience”

Despite enrolling twice at the private liberal arts Carleton College, in Northfield, between 1962 and 1964, and then for a brief and unproductive spell at The New School in Manhattan, Schjeldahl acknowledged that a “high school diploma was [his] greatest achievement”. This was not strictly true, as he went on to receive several prestigious and honorary awards, including the Frank Jewett Mather Award from the College Art Association, for excellence in art criticism; the Howard Vursell Memorial Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, for “recent prose that merits recognition for the quality of its style”; and, not least, a Guggenheim Fellowship grant, from which he used most of the money to buy a garden tractor at Bovina. But Schjeldahl’s poor grades and anti-

academic credentials only came to be a strength of style. Mixing confidence and self-deprecation, he said that the “only thing that I am a world expert in is my own experience”. He was that rare writer whose description of encountering art made the reader feel that they were experiencing it, too. He privileged an embodied experience of art, of writing that obstinately emerges from being there with the work itself, and that celebrates painting’s ability to combine “our most powerful sense”, sight, and “our greatest physical aptitude, the hand”: “that’s why I use the first person”.

After a short spell in Paris, which he did not think was all that wonderful, Schjeldahl settled in Greenwich Village and immersed himself in the downtown poetry scene. “For about a dozen years” in the long 1960s, Schjeldahl reflected in 2019, “I hung out, drank, and slept with artists who didn’t take me seriously. I observed, heard, overheard, and absorbed a great deal.” He barely slept so that he could make the maximum number of mistakes. One brief yet fortuitous encounter in those heady days was with Frank O’Hara, the poet and Museum of Modern Art curator whose occasional poems often feel proximate to pushing your ear to the brownstone wall and eavesdropping on your more exciting neighbour’s gossip from the night before. He called them “personal poems”. O’Hara stood as a kind of protector for an urbane and gregarious writerly sensibility that the younger poet-critic was beginning to cultivate.

Around a year later, in July 1966, O’Hara died in a dune buggy accident on Fire Island. Schjeldahl penned a celebrated obituary in The Village Voice (where he was later art critic from 1990 to 1998): “Everything about O’Hara is easy to demonstrate and exceedingly difficult to ‘understand’,” he wrote with characteristic clarity. “And the aura of the legendary, never far from him while he lived, now seems about to engulf the memory of all he was and did.” The same might be said of Schjeldahl.

In the 1970s, Schjeldahl set out to work on an ultimately abandoned biography of O’Hara, and recorded hundreds of hours of interviews with the survivors and hangers-on of the New York scene. The project was resuscitated from the cutting room floor when Ada Calhoun, Peter and Brooke’s only child and a diligent writer, discovered the recordings by accident. In June 2022 she published the widely acclaimed Also a Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me, a tender and hilarious portrait of a writer and father, who may have had shortcomings in the latter role but who never missed as a chronicler of New York’s art scene during the course of half a century. “I always said that when my time came, I’d want to go fast,” he reflected in “The Art of Dying”. “But where’s the fun in that?”

• Peter Schjeldahl, born Fargo, North Dakota, 20 March 1942; married Donnie Brooke Alderson (one daughter); died Bovina, New York, 21 October 2022.