In Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel Le Città Invisibili (invisible cities), the Great Khan expresses surprise that among the many fantastical tales Marco Polo has told him about the extraordinary places he has visited or imagined, he has never once mentioned his homeland. “Where else did you think I was talking about?” says Polo. Asked by the emperor to give a full account of Venice “as it is”, he demurs: “Perhaps I’m afraid that if I talk about Venice it’ll be lost to me. Or perhaps, by talking about other cities, I’ve already been losing it, little by little.” It is a persuasive trope: the city on water, labile and fragile, only ever to be glimpsed as a scintillating reflection of something else.

Appropriately, maybe, Jonathan Keates’s sumptuous and authoritative history of Venice does not begin at the beginning, but rather at a historical re-enactment of the beginning. We have tickets to see Verdi conduct the first performance of Attila at La Fenice (as the former chair of the Venice in Peril Fund—and an official of the Order of the Star of Italy—Keates clearly draws plenty of water on the city’s social and cultural scene). It is 1846, the twilight of Venice’s Babylonian captivity under the Habsburgs; but the dawning of a unified Italy is still two decades away.

In the opera, Venice is portrayed as the mythical creature she has always in some senses been. (Thanks to the silty oblivion of the Venetian lagoon, little survives from her earliest days, so there is nothing much left to contradict the myth.) In the fifth century, a number of small settlements in and around the lagoon are swelled by tides of refugees, driven from Aquileia and elsewhere by rampaging Huns. By around the year 600, this ragtag community will have coalesced into some sort of fixed political entity, with some sort of affiliation to the Byzantine exarchate; and, as of about 700, a leader, or Doge, appointed by distinctively, though not scrupulously, constitutional means.

Cunning statecraft

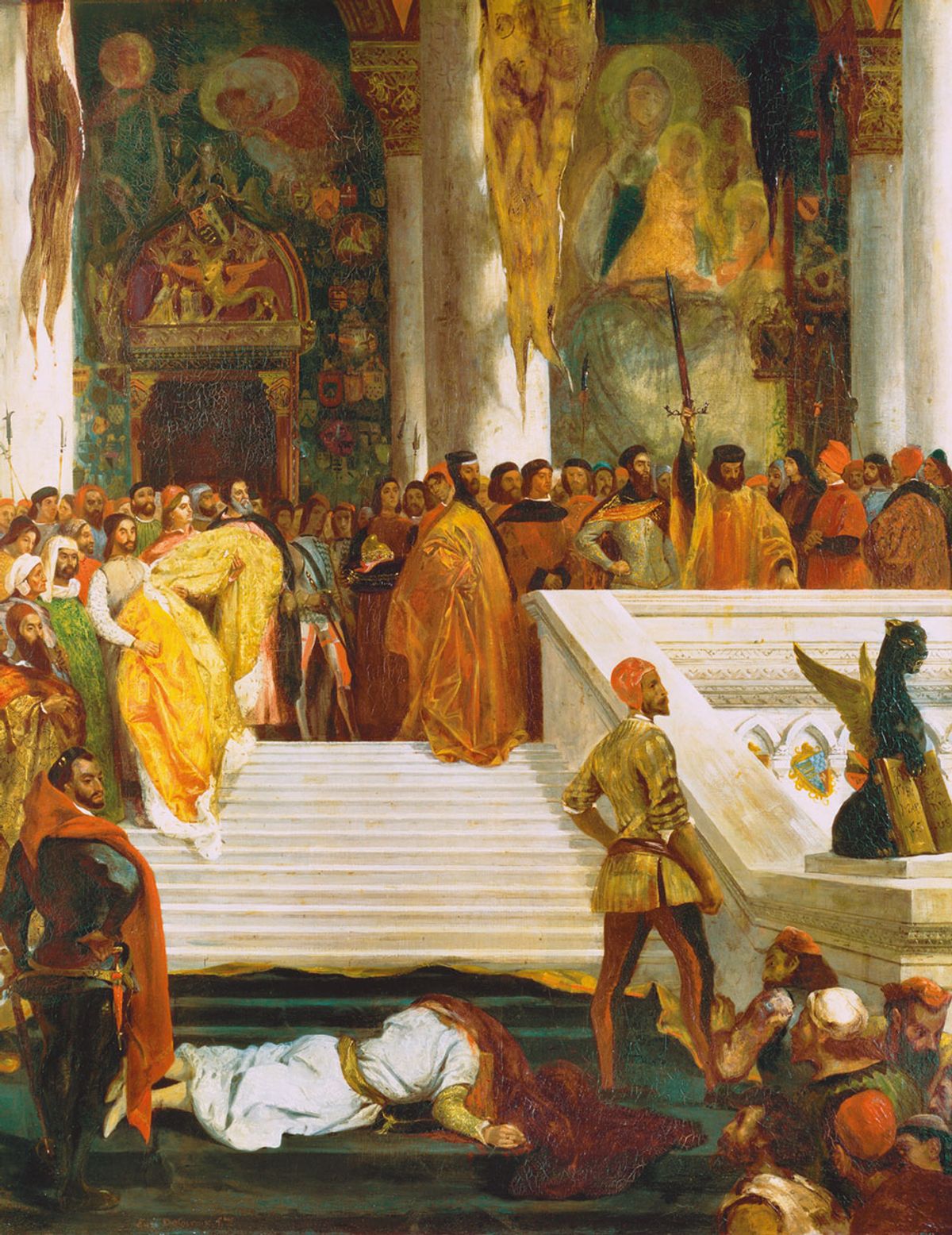

In general terms, what comes next is widely known: trade, wealth, expansion, a reputation for cunning statecraft and flagrant double-dealing; an adroit ability to play East off against West, culminating in the Oedipal assault on Constantinople in 1204; lashings of lovely art (both plundered and created in-house); a series of conflicts with Italian city states, and the possibly ill-advised acquisition of a mainland empire; a period of diminishing returns and genteel decline as the city becomes the Las Vegas of early-modern aristocratic Europe—cue Vivaldi, Casanova, masks, syphilis, Byron and so forth; Napoleon, Austria and the Risorgimento; Ruskin, Whistler and Sargent; the environmentally catastrophic industrialisation of the mainland at the turn of the 20th century, and recent attempts to shore up this beautiful, precarious place using state-of-the-art flood defences—which have failed to work at least once—and, most recently, a ban on the enormous cruise ships that have prowled round the archipelago in the past few years like grazing dinosaurs.

What comes next is… a period of diminishing returns and genteel decline as the city becomes the Las Vegas of early-modern artistocratic Europe

In all of this Keates proves an unfailingly urbane and largely trustworthy cicerone. This kind of assured, patrician, big-picture history has fallen out of favour somewhat; there are a couple of occasions when La Serenissima falls into the same trap as, for example, Christopher Hibbert’s “biography” of Rome: that of conflating character and destiny.

It seems not so much wrong as unhelpful to describe Marino Faliero, the “bad doge” who was executed in 1355—his successors in office would always have an executioner following them around as they pursued their public duties, to remind them that, round here, no one was bigger than the state—as “surly and unforgiving”. A more useful observation might have been that his attempted coup would surely have succeeded but for the unfailing self-interest of the patrician families who filled the pages of the so-called Libro d’Oro, the stud book of Venetian nobility, from which the republic’s leading officials were chosen. (This practice led to some diminishing returns, too.)

As for how the city’s history is inscribed in what the visitor actually sees, Keates seems sound, if a little workmanlike. The big names, the Bellinis and the Tiepolos, the Stravinskys, the Peggy Guggenheims, all get a mention. But as someone who seems acutely aware that at least some women enjoyed freedoms in Venice that were unavailable elsewhere, he might have squeezed in a few words on the 18th-century painter Giulia Lama, say: not a prolific artist but a good one, and the creator, among other things, of a series of powerful and voluptuous male nudes.

While Keates laconically acknowledges the importance of the Biennale and the film festival in maintaining Venice’s cultural vitality, La Serenissima shares with other such books an implicit distaste for most things modern. (He is particularly down on Nicholas Roeg’s 1973 film Don’t Look Now.) But I think more might have been made of composer Luigi Nono, architect Carlo Scarpa (both Venice born), Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky, and the many other brilliant people for whom Venice has been a refuge and an inspiration, a place to dream and create, over the past century or so.

• La Serenissima: The Story of Venice, by Jonathan Keates. Published 16 November by Head of Zeus, 496pp, 100 colour & b/w illustrations, £40 (hb),

• Keith Miller is an editor at The Telegraph and author of St. Peter’s (Harvard University Press)