A number of looted artefacts returned to Turkey and Italy in the past three months have been revealed to be from the private collection of prominent American philanthropist Shelby White. The objects were seized from White's Manhattan home over the past 18 months, as part of a longstanding investigation scrutinising her collection's provenance.

Search warrants issued by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office on 28 June, 2021, and April 27, 2022, seen by The Art Newspaper, list five and 18 works, respectively, that Homeland Security agents found “reasonable cause” to believe were stolen. According to the documents, they constitute evidence of criminal possession of stolen property in the first, second, third, and fourth degrees, as well as of a conspiracy to commit those crimes.

Matthew Bogdanos, the chief of the Manhattan DA’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit, declined to comment because the case is active. White also chose not to comment, telling The Art Newspaper: "I really don’t have anything to say."

White is a major donor to institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she is a trustee and board member, and to New York University, whose Institute for the Study of the Ancient World she founded in 2006 through a controversial $200m gift. Along with her late husband Leon Levy, whose eponymous foundation she now runs, she built a collection of ancient art representing ancient Near Eastern, Greek, Etruscan, Roman, and other cultures. White and Levy also gave a gift of $20m to the Met, and in 2007 the institution named a monumental gallery to Greek and Roman art the Leon Levy and Shelby White Court.

This is not the first time the Levy-White collection has been scrutinised for looted objects. In 1990, more than 200 objects from the couple’s collection were displayed at the Met in the exhibition Glories of the Past: Ancient Art from the Shelby White and Leon Levy Collection; a decade later, archaeologists David Gill and Christopher Chippindale published a study in which they found that 93 percent of the works on display had no known provenance. In 2008, White handed over ten classical antiquities to Italian authorities, as well as two fourth-century BCE objects to Greece. In 2011, the upper torso of the Weary Herakles statue, jointly owned by Levy and White and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and exhibited in Glories of the Past, was returned to Turkey.

A section of an Anatolian columned sarcophagus from the ancient city of Perge, dated between 170 and 180 CE

Courtesy of the US Consulate General, Istanbul via Facebook

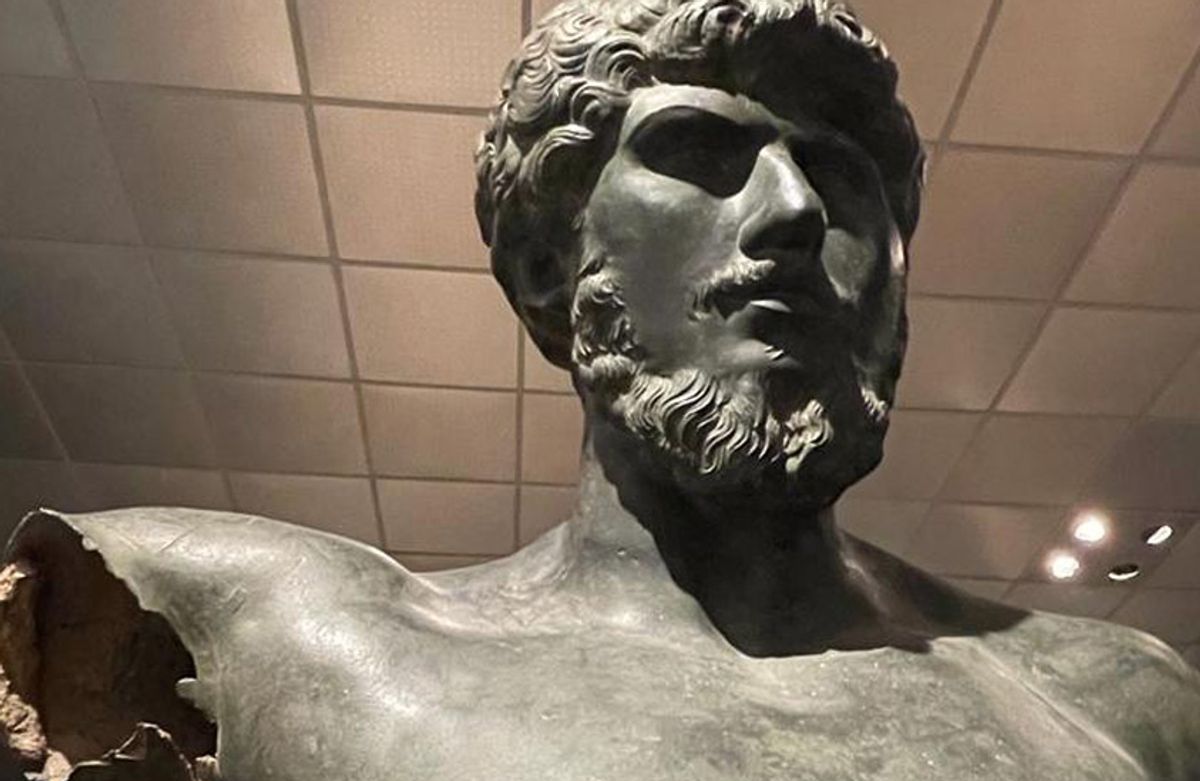

Several works published in the Glories of the Past catalogue are among those seized in recent repatriation efforts. In October, a life-size bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Lucius Verus, dated to the late-second to early-third-century CE, and four sections of an Anatolian columned sarcophagus from the ancient city of Perge, dated between 170 and 180 CE, returned to Turkey following joint repatriation efforts between the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and Turkey’s Culture and Tourism Ministry. The 27 April search warrant to White lists the statue's value at $15m and the sarcophagus fragments at $1m.

Both works were unveiled during a repatriation ceremony at the Antalya Museum on 13 November, alongside four other looted objects, including an early Bronze-Age marble Kusura-type idol and a figurine of Apollo. According to the US Consulate General in Istanbul, the artefacts were extracted from illegal digs in Turkey more than 50 years ago and smuggled into the United States. The previous owners of all six works were identified by Hurriyet Daily News as two auction houses and an unnamed collector in the United States.

But Gill, an honorary professor in the Center for Heritage at the University of Kent, was quick to make the link to White, noting on his blog Looting Matters the objects’ appearances in Glories of the Past. Gill has also published a list of objects formerly in the Levy-White Collection that have been returned so far. Many of them were identified by his former student, Christos Tsirogiannis, a forensic archaeologist and antiquities trafficking expert affiliated with the Ionian University in Greece, who has been sending photographic evidence to the Manhattan DA’s office.

The list on Looting Matters names artefacts seized this year from White’s apartment and repatriated in September to Italy: a red-figure calyx krater (around 515 BC, valued at $3m); an Apulian guttus with a ram’s head spout (around 330 BC, valued at $15,000); and two fish plates, attributed to the Cuttlefish Painter and the Perrone-Phrixos group of painters (mid-fourth-century BC, both valued at $20,000). The Art Newspaper also identified among the seized objects a "Bronze Bust of Man" (first-century BC, valued at $3m); a cauldron with four animal heads (sixth-century BC, valued at $150,000); and a bronze spiral brooch (valued at $25,000) that were formerly in White’s possession. They counted among 58 antiquities that the Manhattan DA returned in September, including 21 from the Met.

At least one other object, a 700 BCE ritual dinos seized from White’s collection under the June 2021 warrant, has also been returned to Italy. It was among the almost 200 looted Greek and Roman artefacts reclaimed from museums and homes around the United States in December 2021, in what officials described as the largest single repatriation of relics from the US to Italy.

White has yet to be named in any official repatriation notices, but Gill anticipates that more announcements will come from the Manhattan DA’s office. “I think it’s very telling that they haven’t said it was Shelby’s,” he says of the returned artefacts. “So this is now part of a clearly much bigger investigation … We’ve had material go back to Italy and Turkey. I think there is material due to go back to Greece.”

Museums, he adds, should take heed and properly assess future loans from White and Levy’s collection. “Clearly, they’ve acquired a number of objects that have been dug up illicitly and removed from their countries of origin outside the legal framework,” he says. “I’m sure they would say they’ve acquired things in good faith. But the scale of looting that we know—they needed to have done their due diligence before they acquired it. And museums need to do their due diligence when they’re accepting loans.”

But Tsirogiannis says he is not optimistic about museums changing their ways. “The antiquities market and the museums do the same that the collectors are doing: they are not checking their objects with the authorities; instead, they are trying to hold on to them for as much as possible, thinking that they may get away with it,” he says. “But in reality—maybe without even wanting to realise it—they are waiting for the inevitable: the authorities to knock on their door with a warrant. It is their choice to follow this strategy, but they should have known by now that this doesn't work, and that they should change their attitude.

“The recent case on Shelby Whites collection, again, is another proof, among the many, of this point.”