The story of the Everglades is one of blurred binaries—between water and earth, between freshwater and saltwater, between utopia and dystopia. It begins in the tributaries of the Kissimmee River, through which rainwater courses into Lake Okeechobee, in the centre of the state. Years ago, when Lake Okeechobee overflowed, that water would creep through the freshwater marshes of the Everglades to empty into the Atlantic Ocean.

That flow created North America’s largest wetland, and an ecosystem found nowhere else on Earth. However, since Florida annexed the Everglades through the 1850 Swamp Land Act, the state has drained sheet flow from Lake Okeechobee through a complex network of canals, pumps and levees. Today, the wetlands are less than half their original size. Marjory Stoneman Douglas, the journalist who rallied the Everglades conservation movement, once called the region a “river of grass”, as apt a moniker as can be imagined—not quite land, not quite sea, but all fearsome beauty.

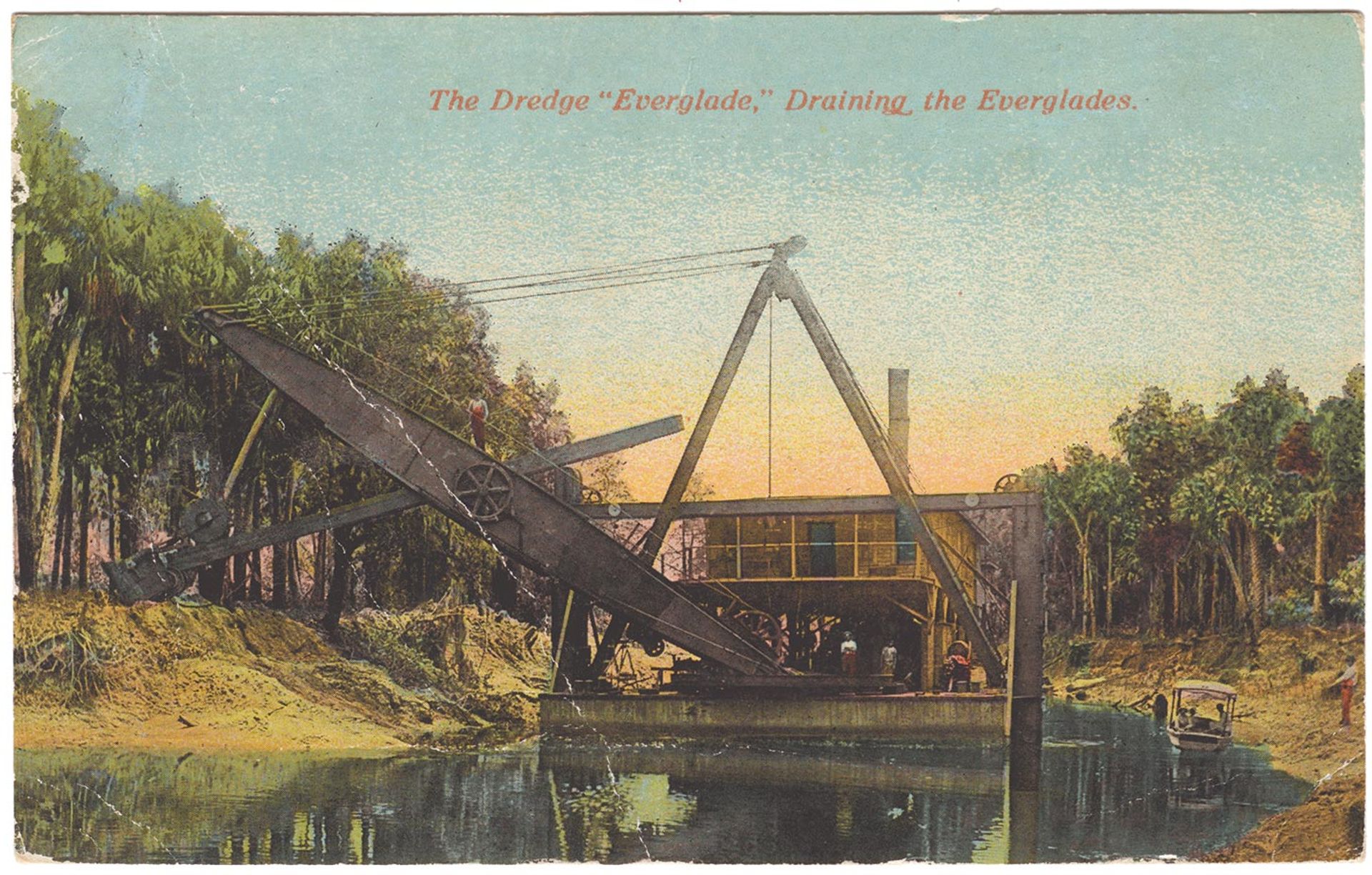

A picture showing the swamps of the Everglades being drained, around 1910, in order to create agricultural land HistoryMiami Museum

By contrast, humans have not just flowed through the Everglades, but called it home. The Seminole and Miccosukee tribes never surrendered to white settlers and evaded capture in the Everglades, its dense sawgrass and shallow water untraversable by most vessels. The region was also a haven for enslaved people fleeing the US via the Saltwater Railroad, a migration stream whisking escapees to freedom in the Bahamas. Later, years before Everglades National Park was established in 1947, Black Americans disproportionately made up the Civilian Conservation Corps, deployed to build infrastructure in the region after the Great Depression.

“They’d send people of colour to the most remote locations,” says Cornelius Tulloch, the creative director of the non-profit Artists in Residence in Everglades (AIRIE). “There’s a lot of recent history to uncover about these communities and their relationship to the Everglades, which isn’t too far from where we are today.”

Tulloch is one of many artists who have made the Everglades their muse over the years. Some, like the wildlife artist John James Audubon and the photographer Clyde Butcher, brought an outsider’s eye and appreciation for the region; others, like the Seminole environmental activist and artist Samuel Tommie, document landscapes they have known their entire lives.

For more than two decades, AIRIE has partnered with the National Park Service to house boundary-pushing contemporary artists onsite at Everglades National Park. In a month’s time, artists will have produced an interdisciplinary project that centres the Everglades in some way. A former AIRIE artist in residence himself, Tulloch collaborated with other current and former AIRIE artists to create Passages, an installation tracing a sunset journey through the Everglades sawgrass. The installation, which will be unveiled on 2 December at the inaugural AIRIE Art and Environment Summit, coinciding with the national park’s 75th anniversary, recalls the fugitive journeys of those who traversed the Saltwater Railroad generations ago.

A striking Purple Gallinule, a wading bird found in the national park Cheri Alguire

“Honestly, I feel like my AIRIE residency never ended. I’m still in conversation with people who have stories I’d like to continue to follow up with,” Tulloch says. “Artists are becoming this bridge between things that the park hasn’t necessarily always focused on or had the time or resources to document.”

The ways that the park has documented the region come under a rare spotlight in an exhibition at the park’s Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center. Through Eminent Eyes brings the contributions of national park photographers to the fore, and is a sister exhibit to HistoryMiami Museum’s Traversing the Wilderness exhibition on transportation in the Everglades (until 12 February 2023). Many of the photos in Through Eminent Eyes position park rangers as avuncular guides, showing off regional flora or teaching youngsters how to pitch a tent. Others feature more plentiful fauna of the Everglades. “M. “Woody” Woodbridge Williams, a national park photographer in the 1960s and 1970s, captured tree frogs and a snoozing barred owl in his pictures.”

“Because these photographers were employees of the National Park Service (NPS), very often their work was not credited to them as artists. We know the name Ansel Adams, but these other incredibly talented photographers didn’t get the same billing because the photos were credited as NPS photographs. We wanted to say, ‘Hey, this person was significant’,” says Bonnie Ciolino, an archivist for South Florida’s three national parks.

The park service’s photo collection posits a somewhat bucolic, chummy view of the Everglades. What they do not document are the very real threats posed to the region by urbanisation and climate change, nor less-than-neighbourly frictions about how to conserve it.

The poet, artist and ordained minister Houston R. Cypress, of the Miccosukee Otter Clan, has created several works paying homage to the Everglades region: Inflection Points (2016), a ceremonial reunion, then repatriation, of water from 13 sites in the Everglades watershed; …what endures… (2021), a ruminative, spiritual short film; and the collaborative Every Step Is a Prayer (2021), which Cypress describes as a “cinematic land acknowledgement and prayer ceremony”. Cypress also leads airboat excursions in the Everglades through Love the Everglades, the advocacy organisation he founded.

An observation tower at Shark Valley, 30 miles west of Miami, provides panoramic views across the Everglades’ sawgrass marsh Andy Lidstone

But Cypress nurtured his connection to the land completely outside the park’s grounds, having grown up hearing stories about his grandparents being forced out of what is now Everglades National Park at gunpoint. Despite growing up on the adjacent Miccosukee Indian Reservation, Cypress did not feel comfortable visiting the park until his late 20s and early 30s.

“Between negotiating the entrance fees, talking to park rangers and dealing with activities around Everglades restoration that compels our tribal government to get into conflicts with the park, it always felt off-limits for me,” Cypress says.

Today, he says the state’s conservation priorities tend to diverge significantly from that of the Miccosukee Tribe’s environmental advisory committee, on which he serves.

“I like to characterise some state departments and agencies as water mismanagement, not water management,” Cypress says. “The South Florida Water Management District and others flood our tree islands to protect cities and big agricultural industries, sending polluted water down to where we live.”

Florida’s kidneys

To explore the extent of the region’s pollution, this autumn four explorers embarked on an expedition to collect water samples in remote corners of the Everglades, many of which were only accessible by canoe. The group traced a near identical route traversed 125 years ago by the amateur scientist and outdoorsman Hugh de Laussat Willoughby, who also sampled the water in the Everglades.

“The Everglades is the kidneys of Florida,” says the Willoughby Expedition member Harvey Oyer III, an attorney, explorer and archaeologist who has published extensively on Florida’s history. “What we do not know is how efficient those kidneys are. Does it filter just phosphorus and nitrogen? Does it filter microplastics? Does it get rid of PFAS [per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, common synthetic chemicals that do not break down organically], petroleum, personal care products?”

Despite state-decreed initiatives such as the 1994 Everglades Forever Act, which implemented standards to monitor water quality in the region, the filtering function Oyer describes may not be able to withstand the sheer level of pollutants in the water.

“We’re filling in a missing link, because no one had gone into [these remote] areas to test the water,” Oyer says. “Does this answer all our questions? No. But will it contribute to a much larger composite understanding? Yes, it does. We’re just one small contribution to it.”

State, local and federal governments have come a long way from the 1850 Swamp Act in recognising the Everglades’ importance. But the region remains under constant threat from urbanisation. At the same time as the Willoughby Expedition, Miami-Dade County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava locked horns with county commissioners over a controversial motion to move the urban development boundary (UDB) between the Everglades and Miami-Dade county to accommodate a new commercial complex near the city of Homestead. Cava vetoed the attempt to shift the boundary, which was last moved in 2013. As we went to press, the vote has returned to the county commissioners for deliberation.

South Florida now has nine million inhabitants, and is growing. Development skirmishes such as these will likely continue, not diminish—but threats to the Everglades mean threatening the region’s main freshwater source, not to mention the scores of endangered species and wildlife there.

Cornelius Tulloch, of AIRIE, hopes art can at least continue to spark action in the region, as it has for decades.

“I don’t really think we’ve fully grasped the ways [AIRIE is] providing spaces for, and access to, these stories,” he says. “In the years to come, I think we’ll see how much advocacy we’re inspiring, by just doing what we do.”