Earlier this year, the artist Alexandre Diop—whose figurative bas relief compositions combining found materials and painted elements have become highly sought-after among in-the-know collectors—took up a residency at the Rubell Museum Miami, creating some of his largest and most complex works to date. For the Vienna-based artist, whose practice involves sourcing objects from city streets, Miami provided a wealth of material to work with, while the residency allowed him to be fully immersed in his studio practice.

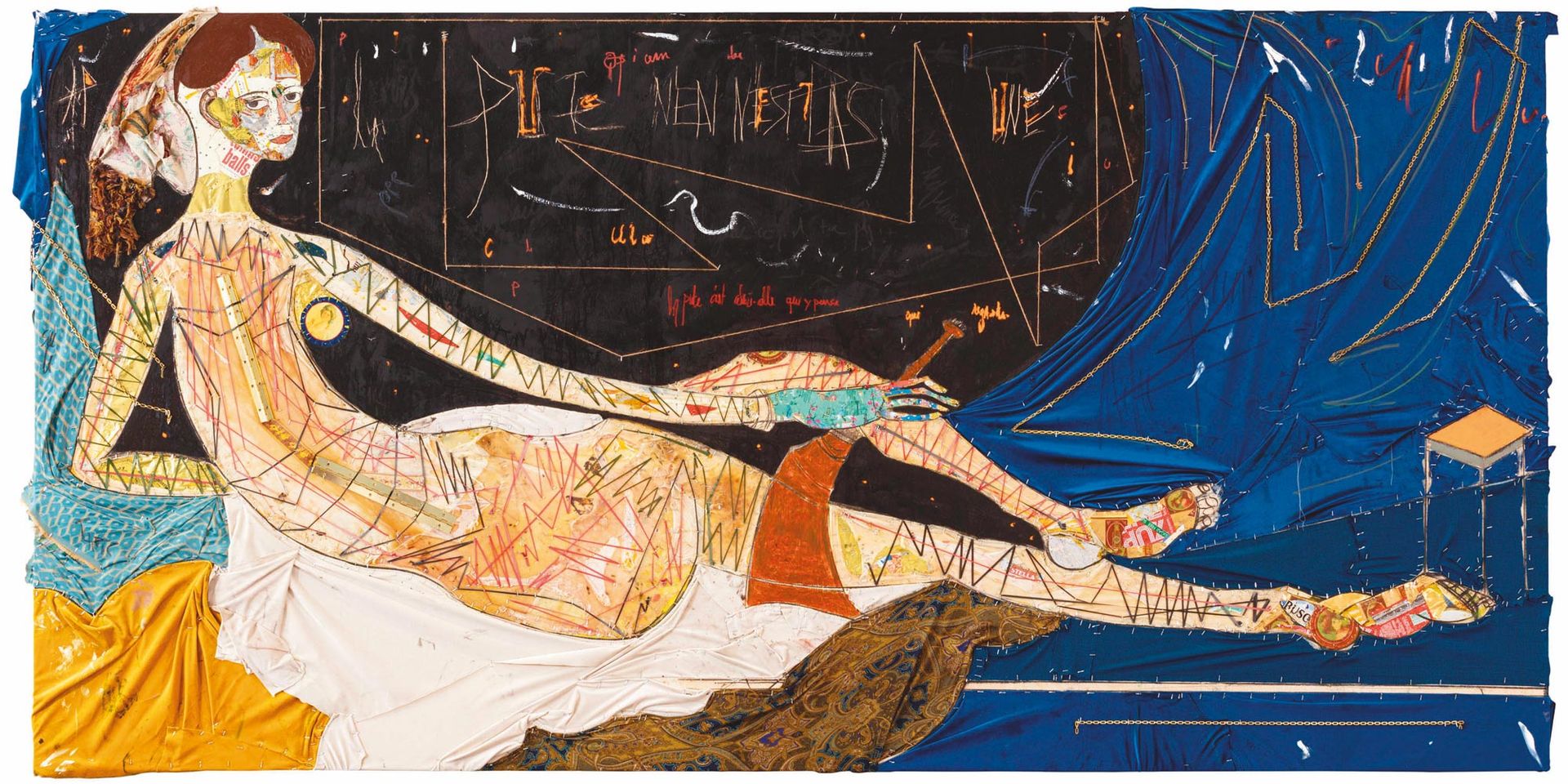

Now, the fruits of that residency are on display at the museum (until 6 November 2023). They reflect his interest in the stories and energies embedded in found objects, as well as his knack for painterly composition and fluency with art history—one of the most arresting works in the exhibition riffs on the trope of the reclining nude odalisque, a form that, in Diop’s rendering, has a spine made of door hinges and a hand formed from tea labels. The artist explains that for him, such found materials are not only building blocks, but portals to different realities.

La Grande Odalisque, Alexandre Diop’s take on an art-historical trope incorporates found objects, such as the door hinges that form the subject’s spine Courtesy of the Rubell Museum Miami

The Art Newspaper: Because of the nature of your practice, sourcing materials from the street, each place must have a distinct impact on your work; how did that manifest in Miami?

Alexandre Diop: I started to collect materials out of frustration, being dissatisfied with the visual effect and materiality of the forms I would make with an academic brush or with pastels. So for a few years now, the material has really become part of my work in the sense that I go digging to find material—it’s maybe 40% of my practice at this point. And I’m not only interested in material because it’s been thrown away, but also in the temporalities it suggests. I’m interested in discussions between generations—so when I find materials from the 1950s or 60s, which are not used anymore, this interests me.

Everywhere I go, I always spend the first week exploring the realities and the possibilities. We live in a globalised world and trash is present everywhere, but of course it is not treated the same way everywhere—in Africa and India, for instance, it’s a paradise for me because there is trash everywhere. But if you go to Vienna or northern Europe, you have different situations. But the process was fast in Miami because it is quite a polluted city. It’s always more pleasant when I can find materials quickly and then start to play with them.

Your work straddles several media and genres: sculpture, painting, assemblage, bas relief. When you’re making these works, how do you think of them?

To be honest, my relation to how I symbolise and verbalise my work has really evolved. For example, I remember almost getting into a fight with my ex-girlfriend because I was starting to say that my work is bas relief, and she said, “No, a bas relief is a bas relief,” and I would say, “I know, but what I’m doing is also a kind of bas relief, that’s how I see it,” and she would disagree and say, “No, now you’re playing with words.” But then when I started talking about them as sculptures, she would say, “No, it’s not sculpture either,” but that was her perspective as someone coming from a sculpture background. So I like to call my works “object-images”. They are objects in the sense that they are wood panels with nails and textiles, and if you turn around the panel you will see all the nails coming through, and this is a really important part of the work—I want my work to be materially strong and heavy. And then I also put a lot of effort into the image on the front, like a painting, because the two-dimensional medium is very practical: it informs the viewer of what the artist wants to show.

I was educated with an African way of seeing—you see things in an object: a spirit, a parent, a god

How do you approach your found-object materials? Do you have an image in mind and you go in search of the right material to express it, or do the materials you find dictate the images?

The materiality is one technique for me, but everything always starts in my head—it may not look like it, but I think I’m really a conceptual artist at the end of the day. And sometimes when I see the material, the art is already there. I was educated with an African way of seeing—you see things in an object: a spirit, a parent, a god. It’s also like Duchamp seeing a fountain in a urinal. So my education is informed by this African way of reusing materials and Duchamp’s way of playing with what already exists.

Diop with one of his colourful paintings. “Every work I make is a reaction to a past work… It’s like I’m writing a book, and every piece is a page” Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects

In the past you’ve likened the process of making a new work to creating a new reality; can you explain that idea and the connections between your works?

I don’t believe that the reality I am in is more real than the objects I create. The objects I make are a more real expression of what life is or the life that I feel. And every work I make is a reaction to a past work. Sometimes I’ll write on a painting the title of a different painting; sometimes the same child from one work comes back in another, or the same moon, the same symbols. It’s like I’m writing a book, and every piece is a page.

• Alexandre Diop, until 6 November 2023, Rubell Museum Miami