Roberto Lugo’s pottery is born from the streets of North Philadelphia. Influenced by hip-hop culture, graffiti art and Black history, his pots, cups and plates memorialise a lived experience that is not often recognised by traditional institutions. But that has been changing in recent years, with major collections acquiring his work, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which features a wide array of his ceramics in its Afrofuturist Period Room installation. In Miami Beach, he has a show at Florida International University’s Wolfsonian Museum, in which he responds to its decorative art collection, as well as taking over the entire façade with a community-driven mural. The artist spoke to us from his studio about the show and what projects he is thinking about next.

The Art Newspaper: You have said that you didn’t really have a lot of access to art when you were young.

Roberto Lugo: I didn’t have any art classes growing up; we didn’t have art in schools at the time. Really, the art that I saw was on the streets, through the murals and graffiti in Philly. The first time I came back to visit [after art school] was my first time going to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. And then, I think it was maybe the third time that I’ve ever been; I actually had a piece in the museum. I wasn’t part of the Philadelphia art scene growing up; I moved away, starting to take art classes. And since I’ve moved back, in the last five years, that’s when I’ve been really trying to connect with the Philadelphia art community.

The art scene there has been growing, too.

Definitely. There’s a culture of craft happening here—people working in glass, ceramics, fibres and metals. And there’s a community of people of colour within all those crafts, who are also creating their own institutions. There’s a studio here called Oye Studios, which is a Black-owned ceramic studio and museum; it had its first exhibition—all Black artists, working in clay—and it was a phenomenal show. Those are the sorts of things that are happening right now.

When you first started getting into ceramics, it was more from the practical side of things, rather than the artistic side.

Initially, I was really just drawn to the idea of making creatively. That wasn’t something that I was exposed to. I identified coming from a place that I referred to as the ghetto, and seeing people making planters out of old tyres, or my father making food processors out of motors from washing machines—that sort of creativity. So when I first started, I made functional pottery, and I was really interested in that idea of learning how to make a good pot.

Then I went to school with a lot of people who had art in high school, who had access to art their whole lives and were way ahead of me. But they were also really impervious to how there were racial implications to a lot of the criticisms they were making of my work, regardless of whether the work was more about functionality or the technical side of things. It always came back to my identity. So that was the moment where my work transitioned into responding to that.

Lugo’s Cherub bookend (2022). Drawing on the Wolfsonian’s collection of historic propaganda, Lugo’s show explores communication in marginalised communities Courtesy of Robert Lugo

For the Wolfsonian show, you’re responding directly to its collection.

The Wolfsonian is a great place to work with because so much of the collection is this historic propaganda; you can see how propaganda played a role in disseminating information, and then we see the results of that. The Second World War is a great example of that, where we see Nazi propaganda being spread through things that people would have in their personal lives. I’m responding to that by thinking a little bit about how propaganda is used to communicate to people in marginalised communities, like the one that I come from. So, for example, I created some vacation posters, but it’s for the ’hood. I’m not thinking about the seriousness of the history of these objects; I’m thinking about how they relate to my lived experience. And through that I think I represent—or, at least, I’m in conversation with—a lot of people who’ve had similar experiences.

Can you give us some other examples of propaganda you’ve responded to?

One of them is a little boy figurine with a missile, meant to make people comfortable with this weaponry. I have a similar porcelain sculpture, but it’s a little boy with a basketball and a backwards hat. And then there’s a Soviet teapot that has imagery of country life: these tractors going through fields, and plowing and tilling. So I have an almost identical teapot, but instead it has low riders and a handgun on the spout, making a nod to both the gun violence where I grew up but also to the idea that these original objects are also violent objects, but they are more indirect. That’s how propaganda works; it’s hinting around, but it’s not being really real. In my work, I like to be overt and confrontational. I like to make things really transparent.

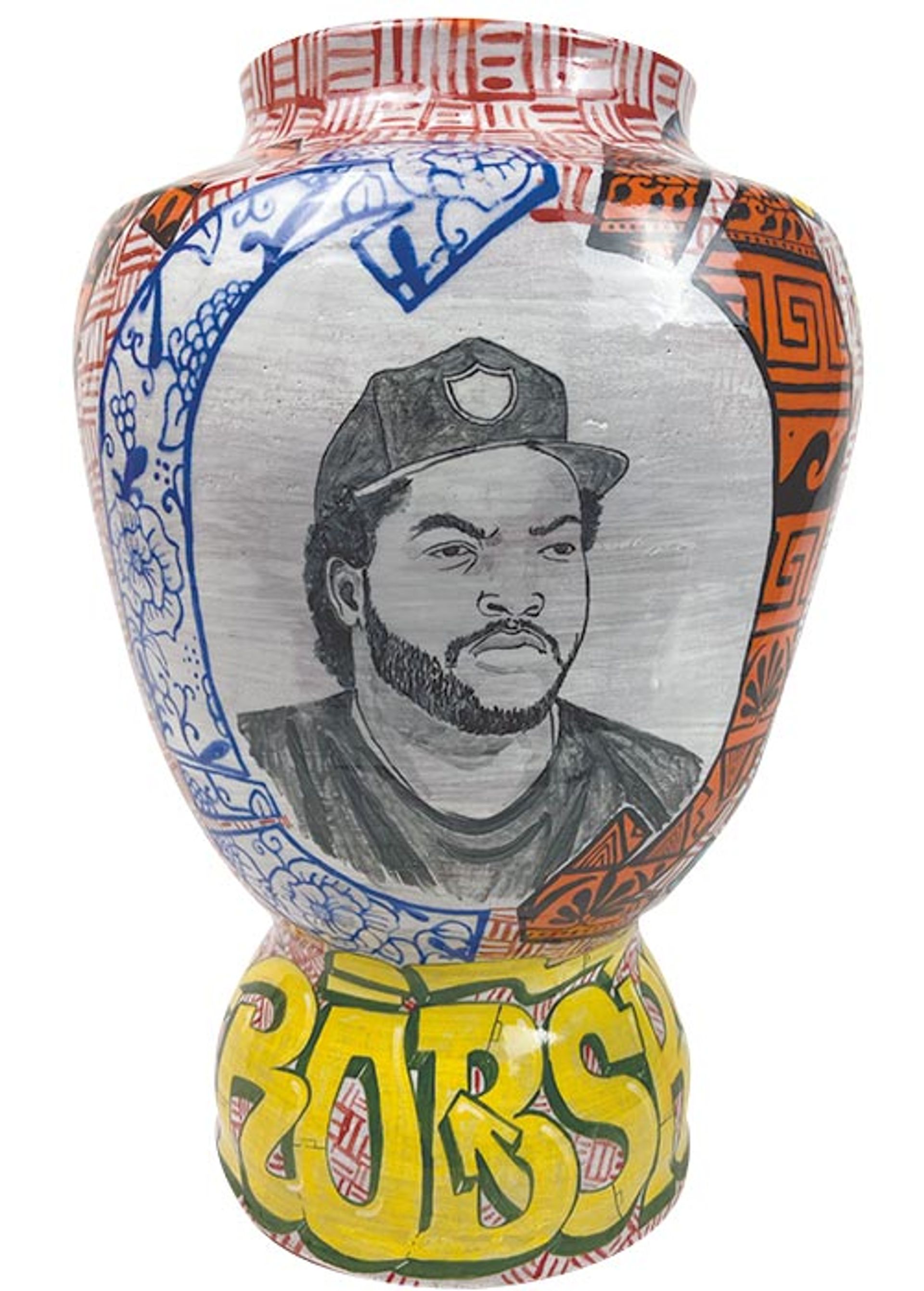

Ice Cube Vase ( 2022) Courtesy of Roberto Lugo

You’re also doing a mural on the outside of the building, and you said that graffiti was the first exposure you had to art growing up. Are you drawing on that?

Yeah, I think so. Exposure to street murals when I was younger had a huge role in how I saw art [functioning] because most of those murals are portraits of people. I really look at murals as the most direct form of art for the public. And it gives some of the most advantageous opportunities to engage with a diverse culture because this particular mural was made in conversation with the Haitian, Bahamian and other communities in Miami, figuring out what might be important to them to have on the exterior of the Wolfsonian. I found some local heroes and folks who had made significant contributions to their communities, and painted them surrounded by some of the patterns that I create, made up of flowers that are native to those islands.

Now that you’ve had your work shown in major museums, what do you see as the next step in your career?

I’ve been interested in getting back to what drove me in the beginning, so I’ve been trying my best to segment studio time so that I can get my hands dirty and start to just play again, without necessarily making something for an exhibition or a sale or any of those things—just focusing on what’s at the heart of my work. I’m looking at more of the history of ceramics; I’m really interested in Greek pottery right now.

It’s very narrative, and archaeologically it’s really important because a lot of history and culture is recorded.

Exactly. And when we think about Western civilisation, a lot of that comes from ancient Greece and our understanding of what people were doing back then. I’d love to be able to use that as a prompt to talk about the stories of today. Also, there’s this really interesting relationship with the orange and black of Greek pottery, and the orange and black of prison uniforms. That’s really the same thing I think about having people from different backgrounds working in the same field; we can look at things like colour and form, and see it in so many different ways. It could make connections that maybe otherwise would never be made. That’s exciting.

• Roberto Lugo: Street Shrines, the Wolfsonian–FIU, Miami Beach, until 28 May 2023