Russia’s contemporary art scene has been blown apart by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with curators and artists dispersed across the Caucasus, especially Georgia and Armenia, as well Europe and further afield to the US and Asia. Those who remain are under increasing restrictions. Even those who support the war have no guarantee of support, as the abrupt cancellation of the ninth Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art earlier this month proved. Vladimir Putin’s “partial mobilisation”, declared on 21 September, has prompted a further wave of departures from Russia. Some of those leaving have found transitional opportunities at art residencies and university fellowships.

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, founded by Dasha Zhukova and her former partner billionaire Roman Abramovich, shut down exhibition programming for the duration of the war in Ukraine and more than half of its curatorial staff have left Russia.

Katya Inozemtseva, the Garage museum’s chief curator, tells The Art Newspaper that she had felt uneasy in Russia for years and saw the war coming in mid-February (Putin launched the invasion on 24 February) prompting urgent preparations for departure with her Ukrainian husband, the sculptor Alexander Kutovoi, and their young daughter. They landed in Milan, where, thanks to the curator Andrea Lissoni and the art historian Marina Pugliese, Inozemtsova secured a part-time museum job. She describes what is happening in Russia as “a rare and destructive machine for all living things, which are forced to hide, learn to be silent, leave and take pills”. Russians, she says, will have to learn “to cancel in your head the truisms about ‘culture and bridges of friendship’”.

Another former Garage museum curator, Valentin Diaconov, is now a critic-in-residence at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. He says he regrets not paying closer attention to Ukrainian art since the Orange Revolution in 2004 and post-2014, which is when Russia annexed Crimea and Russian-funded separatists forced the creation of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics in eastern Ukraine. He says that he admires the energy and engagement of Ukrainian art in the public space.

“The Ukrainian art scene is fantastic, it was fantastic for a number of years, it is still fantastic,” Diaconov says. As part of his residency he is writing about “several artworks that should have alerted us to the gravity of the situation [between Russia and Ukraine]”. He is focusing on Letter to a Turtle Dove (2020), a moody, metaphorical take on the war in Donbas, which began in 2014, by the video artist Dana Kavelina. Diaconov first saw Kavelina’s video in March 2021, after it was recommended to him by the leading Ukrainian contemporary artist Nikita Kadan. “I think if I saw it before that, I would [have been] taking the [political] situation much more seriously,” Diaconov says. He adds that his time in Texas is also providing him with a unique perspective; he and other Russian academics there call it the “Texas People’s Republic” for its parallels to eastern Ukraine.

Georgia, an ancient country in the Caucasus that sheltered artists after the Bolshevik Revolution, has drawn the most concentrated influx of Russian artists and of men fleeing mobilisation. Artists such as the ZIP collective from Krasnodar (whose contemporary art centre was declared a “foreign agent” in May) have also taken refuge in Armenia. Some moved on to Georgia after renewed fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Alisa Yoffe, one of Russia’s best-known young artists, known for her collaborations with the Comme Des Garçons fashion label, was alerted by her fitness trainer in Moscow before the invasion that he was seeing friends heading off to the front. The last works she created in Russia were about the “police terror” and “paranoid state of society” that had taken shape in recent years. She and her mother left Russia for Georgia (which she calls by its indigenous name Sakartvelo) in early March. Her great-grandfather was Georgian and she wanted to continue her study of the country’s “long and complicated relationship with Russia”.

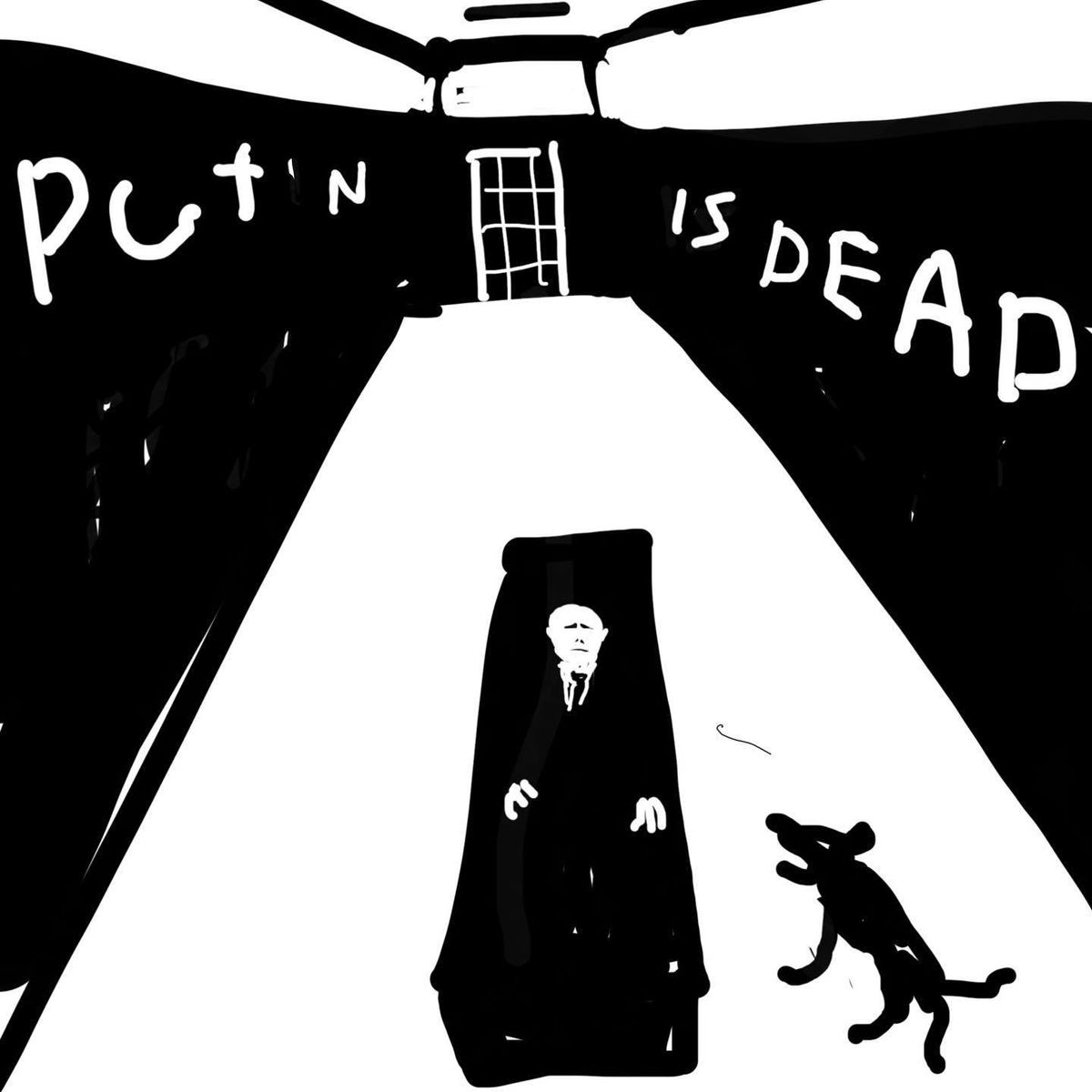

Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, is a centre of Russian anti-war events, festivals and exhibitions, Yoffe tells The Art Newspaper. She and the musician Arseniy Morozov and the game designer Andrei Aranovich, whom she met there, formed a band called Xanax Tbilisi on the online virtual world platform VRChat. The group was scheduled to perform its first single, “Putin is Dead” as avatars in November preceded by an NFT drop of the album cover depicting Putin in a coffin in Yoffe’s signature black and white style.

In the band’s mission statement they write that they are, “a music band playing in the self-blame genre. We acknowledge every crime of Putin's Russia, USSR and Russian Empire. We demand an immediate end to the war in Ukraine and the withdrawal of Russian troops from all territories occupied by the Russian Federation,” including Russian-occupied Georgian territory. One of Yoffe’s recent acrylic-on-fabric works is titled Russia is a Terrorist State.

“Decolonisation” has become a mantra among many artists and curators who have left Russia. The artists Dagnini and Nikita Seleznev spent time at a residency created by US-based creative studio ipureland with the Georgian art patron Ria Keburia’s foundation. “The last illusions that it is possible to change something from the inside have disappeared,” says Dagnini of Russia. “I cannot be in a country that has unleashed a war, threatens [the use of] nuclear weapons and bombs civilians.” She plans to move on to New York, where Fragment, the former Moscow gallery that represents her, is now based.

Seleznev, who has Ukrainian roots—his grandmother’s family was deported from Ukraine to Russia’s Urals region in 1945—says the invasion was “an utter shock”. He and his wife left St Petersburg, where he had his studio, in March, because his anti-war position "became criminally prosecutable in Russia”, he says. Life in Tbilisi is cheaper than in Moscow and most other European cities, and they can stay in Georgia legally for a year. Artists, curators, photographers and designers whom he knows have recently fled mobilisation and many have stayed with him. His project at the residency was called Shaving of the Christ about “how individual life is devalued in authoritarian regimes”.

Artist Masha Shprayzer—who left Russia in April after her attempts to “continue living and fighting” there began to exacerbate the mental issues that are a subject of her art—says that in Georgia she has found a place of empathy: “In all my time here I have never encountered anti-Semitism, which I encountered in Russia even in the artistic milieu.”

The art theorist Natalya Serkova and the artist Vitaly Bespalov—the Moscow-based founders of the Tzvetnik platform, which worked with artists from Ukraine and Eastern Europe—caused a scandal in September with their Instagram appeal for financial help to leave Russia. In October, former collaborators accused them of supporting the invasion and of ties to Russian fascist philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, illustrated in an Instagram post with photographs of Serkova at the wedding of Dugin’s son, an artist.

This year marked a personal commercial high point for the painter and sculptor Ivan Plusch, who had a painting sell for €16,000 at Moscow’s Vladey auction house in June. He and his wife Irina Drozd, also a painter, had already joined other artists, such as Olga Tobreluts, in creating an alternative home base in Hungary in recent years. “Now all my projects in Russia are in limbo,” Plusch told The Art Newspaper.

Curators focused on international projects realised well before Russia invaded Ukraine that any projects with foreign financing are at risk due to draconian foreign agent laws. Olga Sivel, who worked on Manifesta 10 at St Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum in 2014, left Russia for Latvia in 2017 and managed to get her permanent resident status just before that option was cut off for Russians. She is among the founders of Art Ambassadors, a new consortium of curators, event organisers, critics, gallerists and other arts professionals.

Among Sivel’s key advice for Russian artists is to be aware of ill-timed efforts by foreign cultural organisers to bring Ukrainian and Russian artists and curators together in public dialogue. She says that a Ukrainian colleague from Berlin explained that Russian arts professionals should “find out whether there will be Ukrainian participants and whether they have been informed that someone from Russia will be participating,” giving the Ukrainian side the prerogative to decline.

Curator Alexander Burenkov, who has worked as a curator at the V-A-C and Cosmoscow foundations and most recently AyarKut, which aimed “to put [the Russian republic] Yakutia on the world map of contemporary art,” says that working in Russia is now possible only to service the state’s agenda, “based on traditional values, and the readiness to make constant compromises and dialogue with the authorities”. International curators are not fleeing, but putting their abilities and existing European ties into practice, he says. "Portugal, with liberal visa policies, has become an option for those in the art world. Burenkov was granted a highly-qualified specialist visa by Portugal and participated in the AiR 351 residency where he worked for three months on a project about queer ecology and decolonisation of nature.”

Pavel Otdelnov, a prize-winning artist who has used the imagery of Russia’s post-Soviet ruins for his projects, is addressing the invasion of Ukraine in “Acting Out” (until 28 January 2023) at Pushkin House in London. It was already in the works last year as an exhibition about “certain episodes of the Cold War”, he said.

“This year I revisited the concept and turned the exhibition into a reflection on what made this war possible,” he says. “And about my compatriots who have lost their future in their country.”

Russians, he says, are now living “like the end of the 30s in Germany and Italy”, in the very middle of “what always frightened us” and “it is unbearable to understand everything and not be able to change the situation.”

Odelnov says he is grateful to Ukrainians who want to maintain contact, and does what he can to help Ukrainian refugees.

“I understand that now is the worst time to be friends,” he says. “Nevertheless, I try to help Ukrainian refugees as much as possible. I feel their pain with them and I feel ashamed.”