Rarity may add material value to an artwork, but its emotional impact can appreciate even more—an infrequent occurrence in these remotely accessed times. So, imagine my surprise when Practical Effects, an immersive new video installation by Diana Thater, had me falling for a robot. That was not just unusual, but downright unsettling.

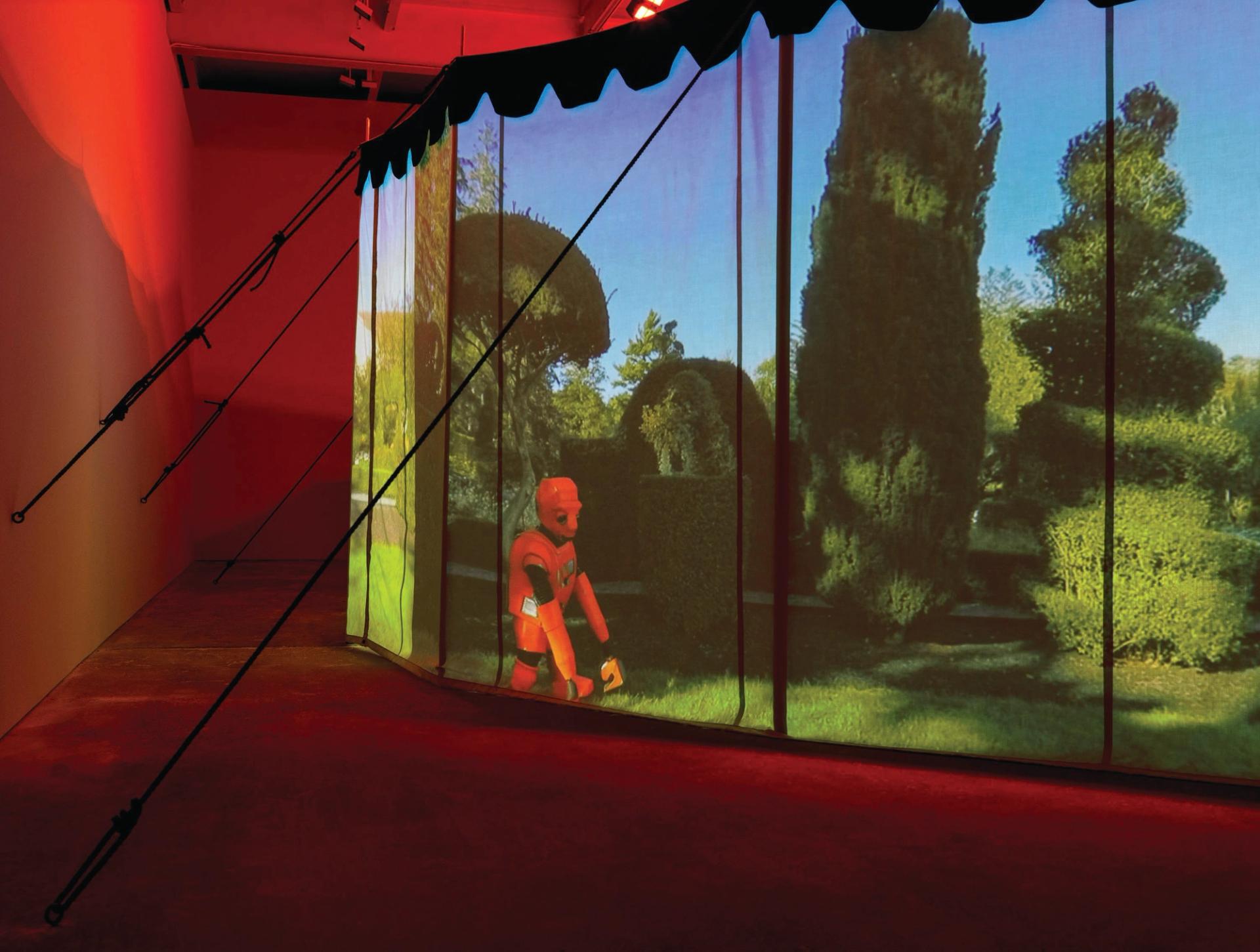

Within a former garage constituting part of David Zwirner gallery in New York, Thater erected a translucent circus tent, lit as if aflame, to serve both as a circular projection screen and as an enclosure for the viewer? Because it's as adorable as a new puppy? (Actually, it resembles J. Fred Muggs, the endearing chimp that in the 1950s, co-hosted the Today Show.)

But what invoked the pathos I felt for the safety-orange suited robot? It resembles J. Fred Muggs—the endearing chimp who co-hosted the Today Show in the 1950s—and is just as adorable. In Thater’s Twilight Zone environment, the robot plays the sole survivor of an imagined disaster that has decimated our planet, wiping out humankind and any vestige of wildlife. Its only companions are the animal topiaries (giraffes, lions, bears, chickens, poodles etc) inhabiting a deliriously lush landscape that, absent human interference, nature has reclaimed for itself.

Installation view, Diana Thater: Practical Effects, David Zwirner, New York, November 10–December 10, 2022. Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Thater is a doom scroller of the first rank. The last time she exhibited here, in 2012, was just after Hurricane Sandy drowned half of Chelsea. Zwirner’s gallery, inundated by five ft of muddy water, was hit particularly hard. Thater’s show was the first in the neighbourhood to open after the dry-out. For that reason, it was a celebratory affair, despite the still-visible devastation outside and the ghastly scene unfolding across the multiple screens within: the aftermath of the 1986 nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl, in Ukraine.

End-times scenarios have driven Thater’s work since 1995, when she began to focus on the threat of extinction to several species of animals caused by thoughtless human intrusion on the natural world. Capturing such creatures—they include a species of rhinoceros, African elephants vulnerable to poaching, and collapsing populations of honeybees—sometimes puts the artist in as much danger as her subjects.

In Kenya to shoot footage of the rhino, the last remaining northern white male (for As Radical as Reality, 2017), she stood enough to rub the beast’s back and scratch its nose. “His hide felt like cement,” she recalled, during an escape from the crush of people thronging her opening at Zwirner. “When he butted me with his head, it was like being pushed by a truck. But what a magnificent creature! He was blind in one eye, so I had to keep talking to let him know where I was, so he wouldn’t charge.” Filming animals in the Exclusion Zone of Ukraine, she said, meant carrying a Geiger counter and being tested for radiation every day. “It’s insidious,” she said, “because you can’t see it.”

Installation view, Diana Thater: Practical Effects, David Zwirner, New York, November 10–December 10, 2022. Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Practical Effects marks a critical departure from Thater’s previous practice. It’s the first time she has worked with representations rather than live animals. However, they are actual shrubs that live in the Green Animals Topiary Garden of Newport, Rhode Island. Still, who can tell the real from its simulation anymore? As someone who has yet to be persuaded that virtual or augmented reality can be good for art, it was nice to hear that Thater’s robot was no Shrek, but a handmade, analogue creation. In Hollywood parlance, it’s a practical effect—in this case, a costumed actor, like the Tin Man, or R2D2 of Star Wars fame. This is also the first time that Thater has featured a species she never depicted before, even if it is a stand-in. (In her film’s projected future, humans either have died out or gone to Mars.)

Thater grew up in Happaugue, New York, enamoured by nature documentaries. Since 1988, she has been living in Los Angeles and teaching at her graduate school alma mater, the ArtCenter College of Design. In Los Angeles, artists almost can’t help but develop movie-industry connections. For Practical Effects, she hired not only the stunt man who waddles around the topiaries but also a movie costume designer, and the fabricator of her silvery tent.

On the other hand, her chief cameraman in Newport was the artist T. Kelly Mason, her spouse. To capture her robot’s point of view, Thater retraced its steps with a hand-held Super-8; to make it look as if he were wearing a Go-Pro. “I wanted to think about what the world would be like after we’re gone, and after they are gone,” she says of the animals.

But the filming, the travel, and the concerns of her work are not all that sets Thater apart as an artist. While she cites Bruce Nauman’s Clown Torture (1987) and Dara Birnbaum’s pioneering use of equipment, video walls and shifts of scale as important to her development, Thater’s meld of architecture, coloured gels, and moving image are her own invention. For example, the only source of the otherworldly lighting and irradiated hues of the Chernobyl piece was the video itself. Like Practical Effects, it plays within a structure that Thater designed to intensify its impact on viewers.

Installation view, Diana Thater: Chernobyl, David Zwirner, New York, November 9–December 15, 2012.

“For 30 years, I’ve used coloured gels to make it possible to see my pieces in rooms with windows,” she says. Black boxes were never for her. “Now," she adds "I see that aesthetic everywhere,” she adds, “but I don’t think young artists know where it came from. It takes experience to do this kind of work; it’s not simple, nor are the questions surrounding representation that I bring up in Practical Effects."

What’s a trailblazer to do? "My next project is in Mongolia,” Thater replies. “It’s the farthest place I could go, except for Antartica. But that’s all I want to say about it now.”