Martin Clayton, the head of prints and drawings for the Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle, has proposed that there may have been two original versions of the Salvator Mundi, produced in parallel by Leonardo’s studio. His conclusions, based on a meticulous study of the composition and technique of the related Leonardo preparatory drapery drawings (now in the Royal Collection, Windsor), were presented at a major conference, organised by Professor Frank Zöllner in Leipzig, devoted to the many questions surrounding the Salvator Mundi project including the status of the controversial $450m Saudi version.

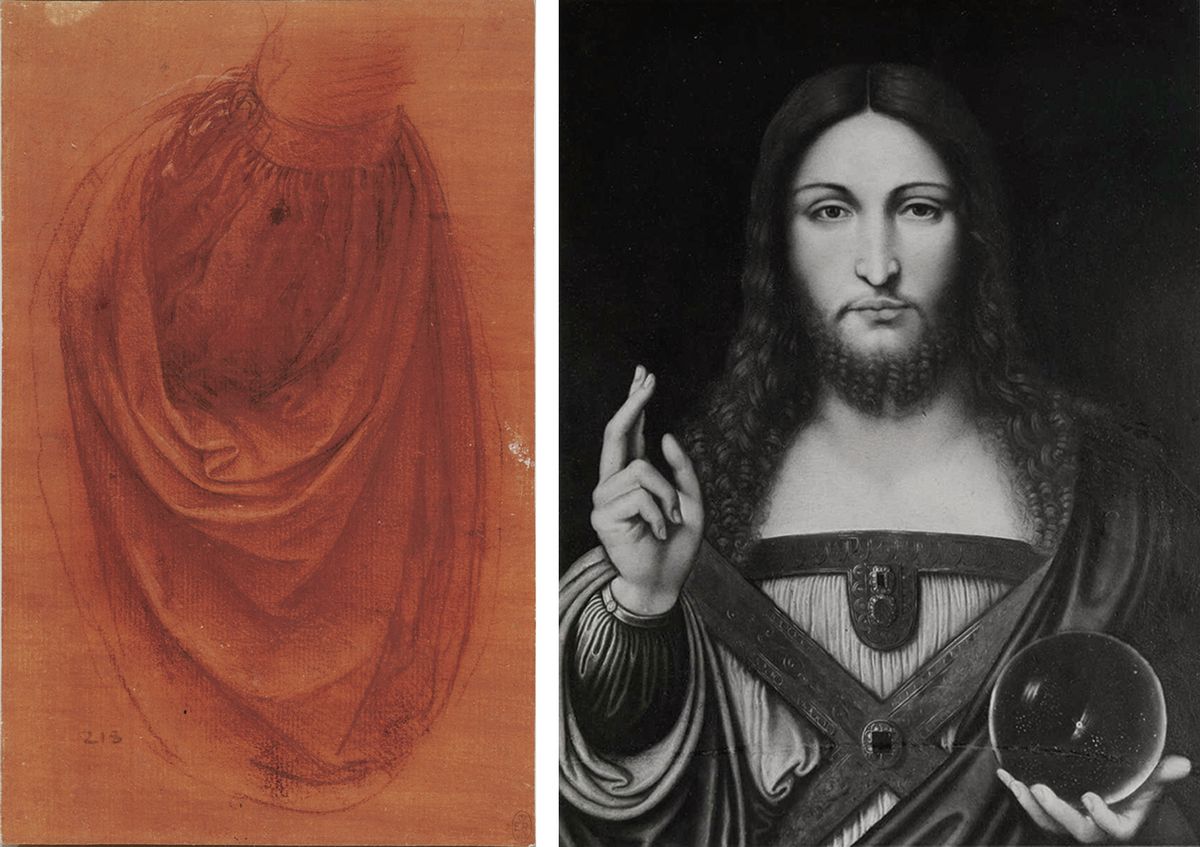

The two drawings, which belong to the great group of 500 that Leonardo left to his workshop, under the direction of his executor and assistant Francesco Melzi, provide no direct evidence of an original Leonardo painted prototype, but undoubtedly served as studio models during Leonardo’s lifetime. Clayton presented a revised dating for the drawings, executed in red chalk on red prepared paper and numbered by Melzi 214 and 218, of around 1508-10.

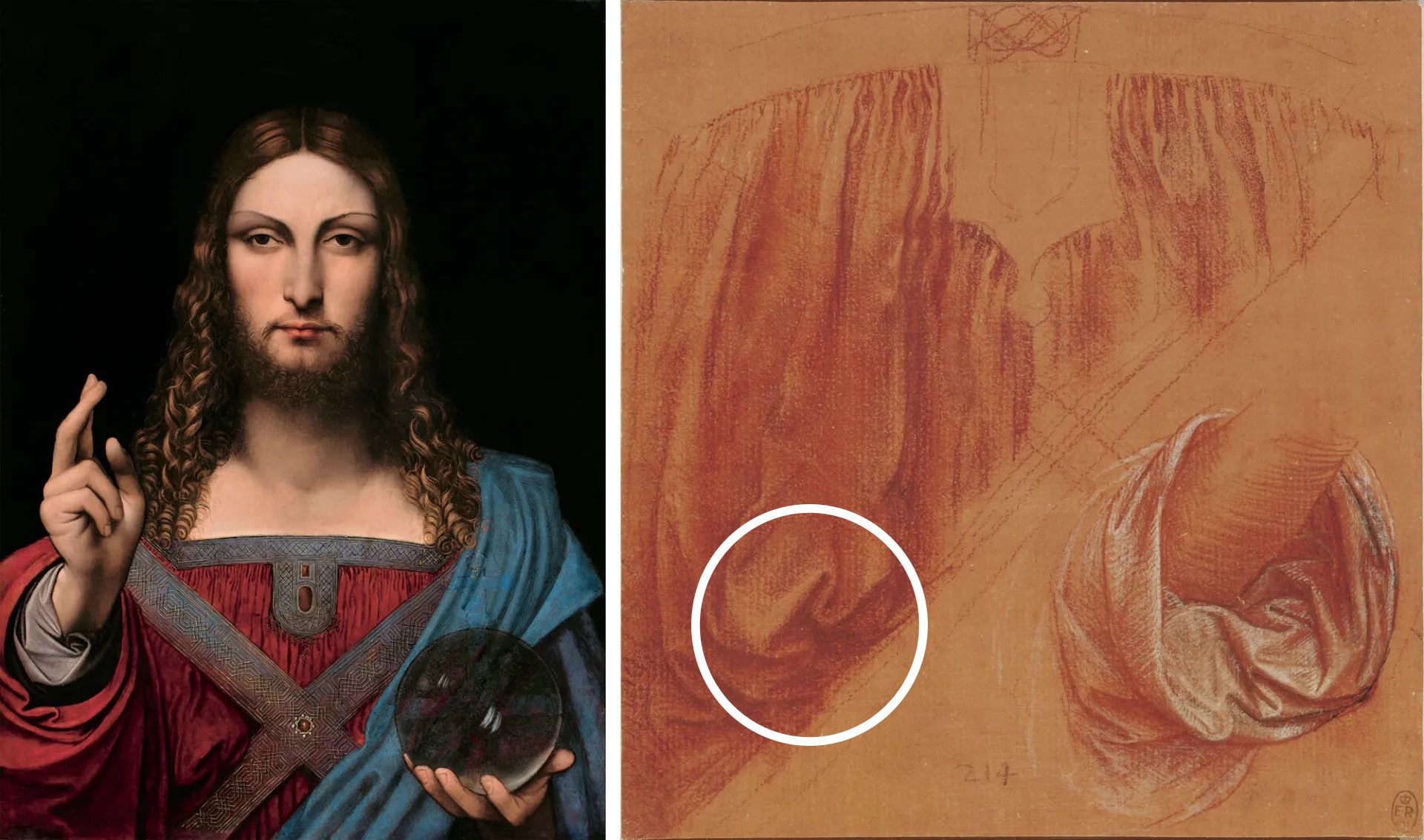

The many painted variants of the Salvator Mundi composition that were based on them, Clayton noted, are represented most faithfully by two works: one formerly in the Worsley and Yarborough collections, last seen at auction in Rheims in 1962; the other the Ganay version, exhibited at the Louvre in the Leonardo da Vinci exhibition in 2019-20 (where the Saudi version failed to appear). Only the Worsley/Yarborough version shows anything approaching Leonardo’s detailed study for the forearm with the cuffed sleeve (214). None of the other known versions follow this model. Clayton suggests that, as with the Madonna of the Yarnwinder and (as is now believed) the Mona Lisa, parallel versions of the Salvator Mundi may have been produced in Leonardo’s studio, but with variations in the details.

The most salient feature of the larger drawing of the drapery of a chest with a hint of crossed bands (218) is the conspicuous omega-shaped fold (circled), which some see as a reference to Christ’s wound and therefore as highly iconographically significant. It is faithfully rendered in the Ganay version, and is still present but distorted in the Naples version; but it is barely recognisable in the confused folds of the Saudi version (perhaps due to its degraded state).

The Ganay Salvator Mundi, which was shown at the Louvre’s Leonardo blockbuster in 2019-20, is the version that most closely follows the omega shape in the drapery (circled), possibly a reference to Christ’s wound

Sketch courtesy of Royal collection. Ganay Salvator Mundi: private collection

Sleeve notes

The involvement of the studio in determining the detail of the inner sleeve, seen in a related study on the same sheet (218), complicates the matter further. A right-handed studio assistant has added white to Leonardo’s left-handed red chalk drawing, perhaps as a means of clarifying the design for use as a studio model. The studio’s role in the preparatory process demonstrates that there is regrettably no simple scenario in this case of: Leonardo drawings; an autograph painted prototype; or a production line of copies by Leonardo’s studio and later followers.

While the technical findings of the Louvre’s secret analysis of the Saudi Salvator Mundi (conducted in 2018) proved that the hands were a late addition to the picture, the Windsor sheets, said Clayton, suggest that the hands were planned from the outset. That said, the angle of the forearm is on a diagonal in the drawings, suggesting a more dynamic approach (more akin to Durer’s Salvator Mundi), as opposed to the stiff vertical position in all the surviving painted versions. As to why the draperies are so unconvincingly delineated in the Saudi version, Clayton was not tempted to venture an answer.

• Read all of our coverage on the Salvator Mundi here and read our special coverage on the five-year anniversary of the sale here