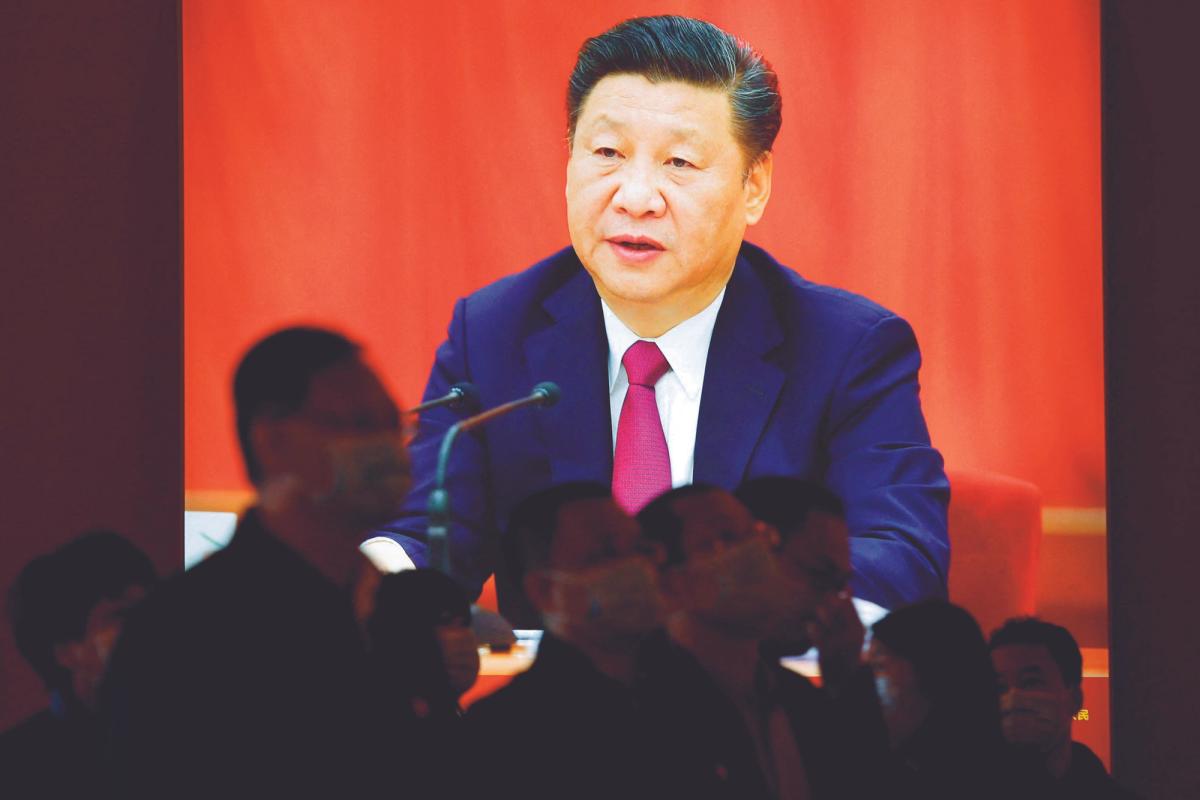

Chinese president Xi Jinping is currently attending this year's G20 summit (15-16 November) in Bali, Indonesia, after almost three-years of being absent from the world stage. After early meetings with US president Joe Biden and his senior advisors, reports say that a new "Cold War" has been avoided despite their oppositional standpoints on key issues such as Taiwan's governance and the war in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, the situation is less conciliatory on the home front. China’s most important visual expression this autumn was its simplest: a collection of red characters hand-painted on two white banners and draped briefly over the Sitong Bridge in Beijing on 13 October. Appearing ahead of China’s national party congress (16 to 22 October), which gave Xi a norms-defying third five-year term as president, the banners, purportedly designed by Peng Lifa, read: “Remove the traitor-dictator Xi Jinping!”

Public protest is rare in Xi’s China, with the public square ever more strictly monitored, but the banners sparked off protests around the world, mostly by the Chinese diaspora overseas, against Xi’s policies, including crackdowns in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, aggressively pursued zero Covid, and curtailment of expression.

“With the rise of Xi Jinping, there has been an overall ideological tightening in China—not just in the arts, but probably first with the universities, media, and gradually hitting contemporary art,” says a curator based in China, speaking on condition of anonymity. “It really seems like the previous tango—three steps forward, two steps back, sometimes two steps forward, three steps back—in the margin of expression in China has come to an abrupt halt, even going into reverse. Some folks joke about the ‘liberal golden age of Hu Jintao’ [the previous president], which, of course, wasn’t that at all.”

Censorship in mainland China, including suppression of the arts, predates Xi’s 2012 rise to power, but the parameters of what is permitted have shrunk steadily since then. Conversationally, artists, curators and critics compare the situation to walls gradually closing in, or a water margin slowly rising.

After a crackdown in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, China in the mid-1990s and 2000s experienced a heady comparative freedom, fomenting the emergence of a now well-established art scene. Explicit references to sex or politics were, as now, forbidden, but anything else, including subtle allegory, was allowed. “Red lines have gotten tighter; what might have flown under the radar are more scrutinised,” says the curator.

Especially since 2019’s protests and subsequent crackdown in Hong Kong, those lines have become blurrier, exacerbating self-censorship. Closed borders and harsh enforcement of zero Covid measures have intensified the sense of control. There is a marked uptick in emigration by the cultural class, says the curator, “though I wonder if the crisis of confidence was mainly due to censorship or to the tough Covid lockdown (and just the wanderlust in normally peripatetic curators and artists)”.

Crucially, Xi’s keynote opening speech at the congress provided some hints as to China’s official cultural agenda, with a call to “promote confidence in its culture, cast new glories of socialist culture”. In an excerpt posted by the National Art Museum of China, Xi declared that China must, “develop prosperous cultural undertakings and cultural industries” with a “people-centred creative orientation, introducing more outstanding works that build the people’s spiritual strength… cultivating a large contingent of cultural and artistic talents with both moral and artistic skills.”

China, Xi went on, should “implement the strategy of driving major cultural industry projects”. While better heritage preservation and the promotion of Chinese art globally seem laudable, the requirements for artists’ moral rectitude signal further rigidity.

Certainly it will not include things such as the performers, led by the artist Chiang Seeta who, on 16 October in Paris, donned Chinese imperial robes and masks of Xi’s face while fighting off giant Covid-testing Q-tips. Or another performance on the same day by Zhisheng Wu, a Chinese student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, who traversed New York’s Time Square clad in 27 of the white hazmat suits worn by China’s Covid enforcers until he collapsed.

Our anonymous curator says: “The party is only getting started: now the Great Leader can truly install those loyal to him at the highest levels, and his power would be even greater.”