An important Gauguin sculpture from Tahiti is not what it seems. Although entitled Idol with a Pearl, the pearl on the forehead was actually added nearly 30 years later, long after the artist’s death. Evidence for the addition has been discovered in the diary of George Daniel de Monfreid, a friend of Paul Gauguin. The Musée d’Orsay in Paris, which owns the sculpture, may therefore consider retitling it.

Idole à la perle—or Tii à la perle (Tii is a Tahitian deity)—was carved in local tamanu wood by Gauguin in 1892. Although now renowned for his paintings, he was arguably the most radical and imaginative sculptor of his time, mixing European and Polynesian motifs. The symbolism of Idole à la perle remains enigmatic. It depicts a naked female in a lotus position, sitting in a niche, overlooked from behind by the larger head of another woman.

Although Gauguin was interested in Polynesian culture, his understanding of their seemingly exotic religious beliefs was limited. Gauguin’s South Seas sculptures emerge partly from his perception of Tahitian society, but mainly from his own imagination.

The female in the Buddhist lotus position has Polynesian facial features, but the decorative headband is his invention. The Buddhist elements of the sculpture are also Asian, rather than Tahitian. They were filtered through Gauguin’s experiences in Paris, where he visited the overseas displays in the Exposition Universelle (world’s fair) of 1889. He believed, largely wrongly, that Tahitian religion and Buddhism shared common Eastern origins. The male figure of the Buddha has curiously been transformed into a somewhat androgynous female.

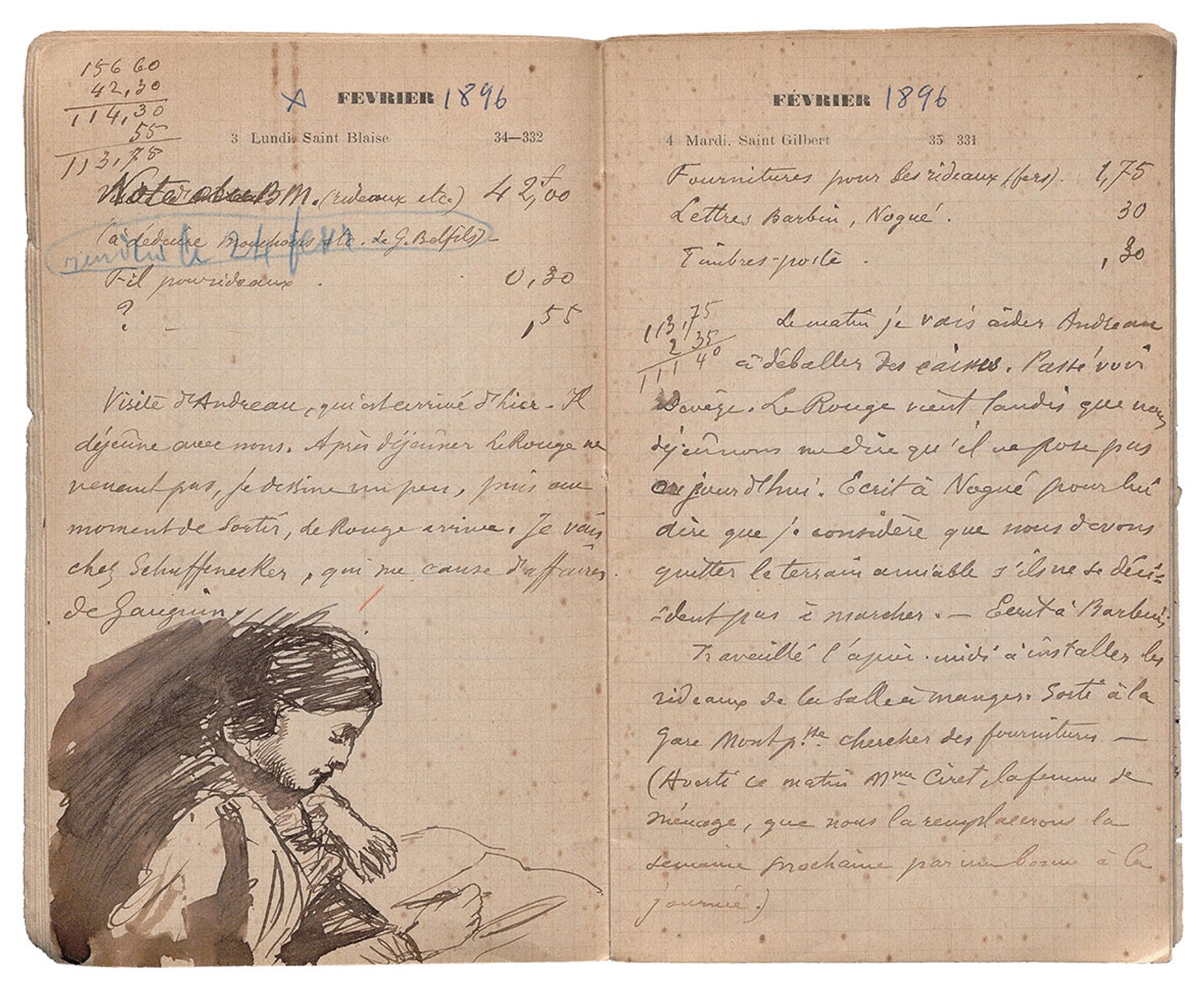

The diaries of George Daniel de Monfreid (a page shown here) reveal the likely origin of the pearl in the sculpture Musée d’art Hyacinthe Rigaud, Perpignan/ArKhênum

Fabrice Fourmanoir, a researcher who moved from Tahiti to Mexico, has been studying the Monfreid diaries. These notebooks have just been acquired by the Musée d’art Hyacinthe-Rigaud in Perpignan, which is holding a major exhibition on Monfreid (until 31 December). Fourmanoir found a key reference to the Gauguin sculpture in the diaries.

On 6 January 1928 Monfreid wrote: “Went to Bourgeois who was kind enough to pierce a little pearl that I kept and I’m going to the Luxembourg [Museum] to attach it to the forehead of Gauguin’s little idol.” Bourgeois, it is assumed, was a Parisian jeweller. The sculpture was about to be put on display at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. It is unclear whether Monfreid added the pearl for the best of reasons or not.

Gauguin had returned to Paris after his first Tahitian stay in 1893, a year after making the cylindrical sculpture, and he then left it with his dealer, Ambroise Vollard. In 1900 Gauguin instructed Vollard to send all his unsold sculptures to Monfreid, who acted as his agent in France until his death in 1929.

In 1951 Monfreid’s daughter promised to donate the idol to the Musée du Louvre and it later passed to the Musée d’Orsay. Since its arrival in the Paris museums it has been entitled Idole [or Tii] à la perle. The work was included in the major 2017-18 exhibition Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist, at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Grand Palais in Paris.

Photographic clue

An 1894 photograph of the work does not appear to show a spherical pearl, but instead a similarly sized flatter object on the figure’s forehead. This has been interpreted as representing the third eye of Buddha, a supposition enhanced by the crossed legs of the idol. Fourmanoir believes that Gauguin’s original flatter object fell off in France or was deliberately removed, to be replaced by Monfreid with a modestly priced small pearl.

Two Parisian museum curators, Claire Bernardi (Musée d’Orsay) and Ophélie Ferlier-Bouat (formerly Musée d’Orsay, now Musée Bourdelle), argue in the Perpignan exhibition catalogue that the pearl was added to possibly replace “a lost original”. But the 1894 photograph raises doubts whether it was actually a pearl.

Last month a spokesperson at the Musée d’Orsay told The Art Newspaper: “We cannot give a clear and final response about the pearl without a further examination of the artwork.” Although it is very unlikely that the museum would consider removing the pearl, since it is part of the history of the sculpture, retitling the work would be much simpler.

Until now Monfreid has been portrayed as a loyal friend of Gauguin, assisting him from France when he was in Polynesia and helping to preserve his works after his death. But Fourmanoir’s studies of the newly accessible private diary leads him to question this. Other entries certainly raise concerns.

On 23 August 1903 Monfreid writes about having heard that day of the death of Gauguin on 8 May. In an astonishingly brief reference, and apparently with no emotion, he records the loss of his friend.

It was only three weeks later that he belatedly wrote to inform the artist’s Danish wife Mette about her husband’s death in the Marquesas Islands.