Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) is an artist whose time has come. The fascination with the Swedish artist’s work has grown since the 2013 retrospective at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and reached a high point with the 2018 Guggenheim exhibition in New York. Painting at the behest of “higher spirits”, Af Klint embraced the spiritualist beliefs of Rosicrucianism, Theosophy and Anthroposophy, while remaining open to contemporary scientific developments (from x-rayographs to research into atoms), which similarly penetrated superficial reality. Her paintings transformed these various sources into an individual imagery that ultimately fulfils her prediction that “the attempts I have undertaken … will astound humanity”.

The long neglect of her paintings exposes the predominance of a misogynist and formalist interpretation of abstraction ill-equipped to accommodate her gender-fluid spiritualist inspiration

In complementary ways, the English translation of the first biography and the completion of the seven-volume catalogue raisonné this year bring order to the fascination, while asserting Af Klint’s position within the historical narrative of non-objective art. The long neglect of her paintings exposes the predominance of a misogynist and formalist interpretation of abstraction ill-equipped to accommodate her gender-fluid spiritualist inspiration. The familiar claim that Wassily Kandinsky made the first Abstract painting in 1913 was part of this modernist tendency, but the contention that this should have been the right of Af Klint’s 1907 works is now firmly established. Her “higher spirits” (named Amaliel, Ananda and Gregor) dictated her Abstract compositions as a mediumistic revelation, while, as Julia Voss unravels in her pioneering biography, the painter’s everyday needs were sustained by family and friends, portrait commissions and, in difficult times, lodgers.

Voss ably traces paths through the networks of the international spiritualist groups in the late 19th century. In Stockholm, these included the photographer Bertha Valerius’s Klöverbladet (cloverleaf) and Huldine Beamish’s Edelweiss Societies. From within these circles, in 1896 Af Klint and Anna Cassel, a close friend and fellow artist, formed an intimate séance group, “The Five”, with Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman and Mathilda Nilsson. Though initially a junior participant, Af Klint emerged as the dominant conduit for the mediumistic messages that determined her great cycle of The Paintings for the Temple (1906-15). As Voss interestingly shows, many of the spiritualists were simultaneously active in the more temporal demand for women’s rights. Af Klint served briefly as secretary to the Association of Swedish Women Artists, founded in March 1910, and Voss draws attention to the parallel activity of Ida af Klint, the artist’s sister, working for equal rights through the Fredrika Bremer Association.

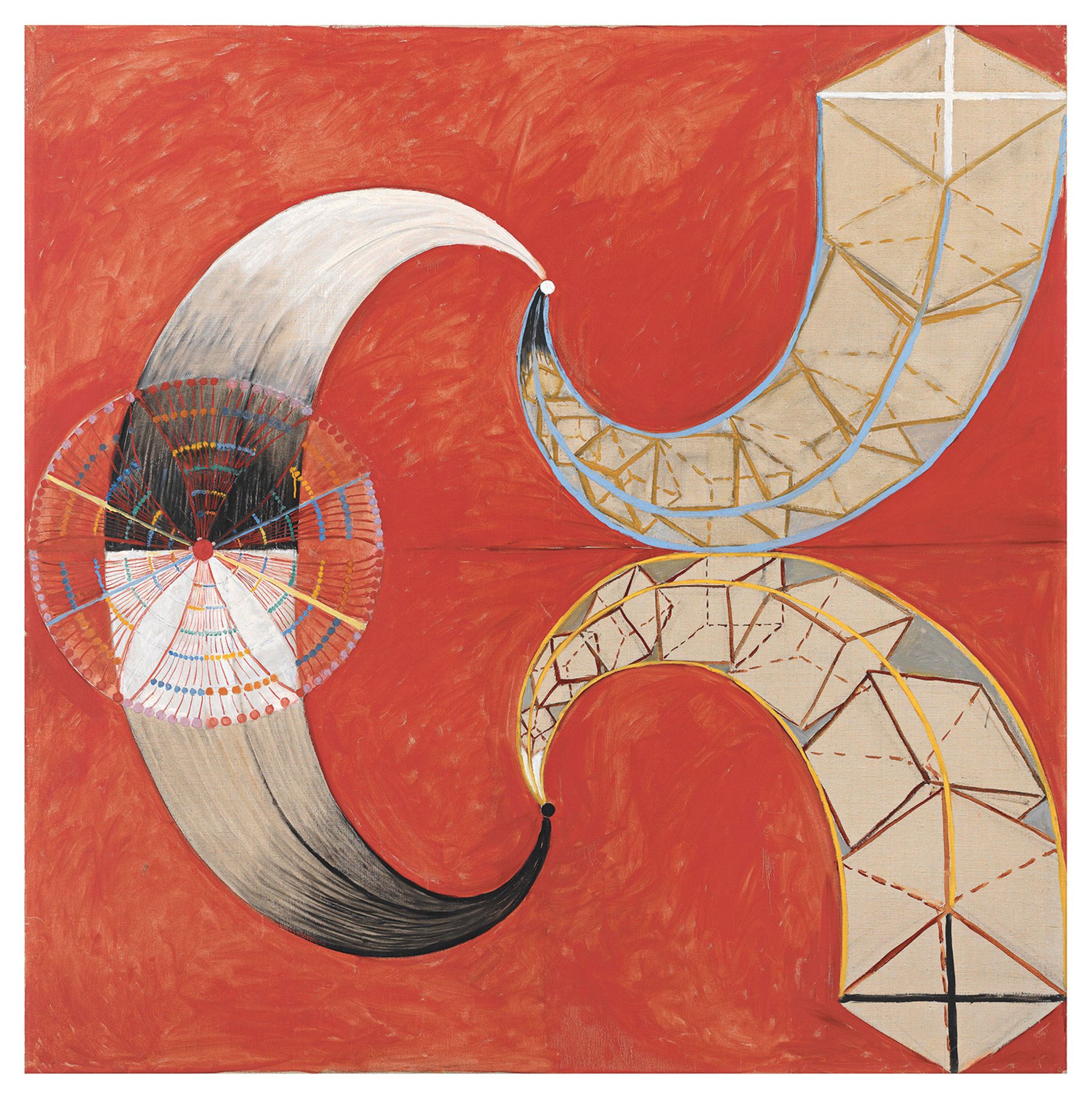

Works such as Group IX/SUW, The Swan, No 9 (1915), were the result, Af Klint believed, of mediumistic revelation channelled through her “higher spirits”—the artist embraced a number of spiritualist beliefs and was a founder of “The Five” seance group in Stockholm Albin Dahlström, courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation

These details, garnered from deep research beyond even the artist’s 26,000 pages of notes cited in great-nephew Johan af Klint’s “Afterword”, help to achieve the correctives Voss sets out in her introduction. As well as distinguishing Af Klint’s own spiritual understanding from the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner’s (rather distracted) interest in her art, Voss links this sociopolitical aspect to the artist’s understanding of the material world.

Crucially, she demonstrates that Af Klint proposed to exhibit the Abstract works on more than one occasion—a factor of critical importance given the painter’s retention of almost her whole oeuvre had fed notions of a withdrawal from public engagement. Af Klint and her companion, Thomasine Andersson, made miniature copies to show to Steiner, hoping for their inclusion in his Anthroposophical centre at Dornach, Switzerland. More concretely, Af Klint presented the originals—although which of them remains unclear—at the World Conference on Spiritual Science held in London in July 1928. Neither yielded sustained interest and, thereafter, she nurtured unrealised plans to build a temple for her work.

Certainly, those astonished by Af Klint’s story should turn to Voss’s biography. Well-served by her translator, Anne Posten, Voss marshals as much of the personal detail as the painter’s surviving notes would divulge and has filled out an account that will surely remain the standard for years to come.

This publication certainly constitutes one of the most handsome catalogues raisonné produced, and those seeking a compendium of these works will be richly rewarded

Last month, the Hilma af Klint catalogue raisonné reached its seventh and last volume. This significant undertaking is edited by Kurt Almqvist and Daniel Birnbaum, scholars closely associated with re-evaluating the artist. Their endeavour benefits from the survival of the abstract works in the Hilma af Klint Foundation. They acknowledge the artist’s own organising principles for her work as well as the register compiled by Olof Sundström after her death. With full-colour and full- or quarter-page illustrations throughout, this publication certainly constitutes one of the most handsome catalogues raisonné produced, and those seeking a compendium of these works will be richly rewarded.

The catalogue order is sanctioned by the artist’s own concentration on the spiritualist paintings to the detriment of her more functional realism. So it is that the first volume (published in 2020) plunges the reader into the closed world of the notebooks made during the séances of “The Five” from 1895 to 1910. They contain urgent sketches, scored by jabbed pencil marks that either staked out or filled in the eventual image.

The second volume displays The Paintings for the Temple made in two marathon bursts, in 1906-07 (notably the series The Ten Largest) and 1912-15, and which constitute the heart of Af Klint’s output. Here, the enjoyment of the works on which her reputation rests more than justifies the publication’s high production values. The editors emphasise the “fluid interchanging of abstraction with figuration, and continued imaging of unseen worlds” but, surprisingly, their laconic introduction somewhat underplays the works’ recently established importance.

The whole sequence as remade by Af Klint in miniature occupies the catalogue’s third volume. Here, the book’s design uniformity slightly obscures the sequence, as several of the notebooks illustrated would be more logically legible if ranged vertically on the page. The notes that Af Klint added are translated but, as the editors’ introduction declares, “textual elements that are part of the artworks themselves have not been translated”. This decision seems surprisingly unhelpful in an English-language catalogue of this nature.

Symbolic geometric watercolours dominated Af Klint’s output in 1916-20 and are covered by the next two volumes. Their delicate control contrasts sharply with the freely handled watercolours of the following two decades gathered in the penultimate volume. These are some of the most atmospheric of Af Klint’s works, stretching the range of her colour harmonies before being complicated by figurative elements.

Academic dexterity

The final volume constitutes a miscellany. Floated free from chronology, it opens with 1880s works as a student at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, which confirm Af Klint’s academic dexterity (a mistranslation of the Swedish “akt” as “act” rather than “nude” creeps in here), and sweeps up her realistic portraits and landscapes. The grouping by genre (but mixing media) obscures any sense of development. This heterogeneity suggests that taste and a view of the artist’s reputation discounted the early material from occupying its logical place as a first volume.

There are conventions associated with catalogues raisonné: they are arranged chronologically, assign a unique number to each work and contain definitive information on the individual pieces (title, date, dimensions, inscriptions), their material (paint, support) and history (provenance, exhibition history, citations in the literature). Beyond the title, date, material and “HaK” number (in a list at the back of each volume), the Hilma af Klint catalogue defies many of these conventions. As she kept the Abstract work there is no need for provenance information—though the works in the final volume are widely distributed—but overlooking recent exhibitions and the wealth of literature on the artist seems something of a disservice. Furthermore, there is no chronology or bibliography.

Somewhat disarmingly, the final volume includes the statement: “It would not have been possible to include all known works from these [genre] groups in a volume comparable in size to the previous ones.” This indicates—rather than lacunae in the knowledge—that a 340-page volume does not suffice to encompass this aspect of Af Klint’s work. It is clearly a matter of judgement, but one that undercuts the claim of these elegant volumes to function as a catalogue raisonné of the whole oeuvre.

• Hilma af Klint: A Biography, by Julia Voss, translated by Anne Posten, published by University of Chicago Press, 448pp, 44 colour & 49 b/w illustrations, £28/$35 (hb), published UK/US 6/19 October

• Hilma af Klint Catalogue Raisonné, by Kurt Almqvist and Daniel Birnbaum (eds). Vol.1, Spiritualistic Drawings 1895-1910; Vol.2, The Paintings for The Temple; Vol.3, The Blue Books; Vol.4, Parsifal and The Atom 1916-1917; Vol.5, Geometric Series and Other Works 1917-1920; Vol.6, Late Watercolours 1922-1941; Vol.7, Landscapes, Portraits and Miscellaneous Works 1877-1941. Published by Bokförlaget Stolpe and Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation for Public Benefit, 2020-22