Jo van Gogh-Bonger (1862-1925) was a remarkable woman, and her story deserves to be told at length. Hans Luijten’s rich and thorough biography, originally published in Dutch in 2019, serves her admirably, giving a full account of her loyalty and determination as she devoted her life to the legacy of her much-loved husband, the art dealer Theo van Gogh, and of his painter brother, Vincent.

Jo Bonger married Theo in April 1889, aged 26, and moved with him to Paris. But he died in January 1891 after only 17 months of marriage, leaving her with their baby son, also named Vincent. She had only briefly met her brother-in-law but inherited responsibility for the hundreds of canvases and drawings that he left. She returned to the Netherlands and for many years ran a guest house at Bussum, near Amsterdam. In the meantime, she entered into practical relations with the artists, writers and dealers who wanted, from their different perspectives, to promote Vincent van Gogh.

This interest in and support for Van Gogh’s work after his death in 1890 came immediately from his fellow artist Émile Bernard and writers such as Julien Leclercq. And within two years of his suicide, exhibitions had been held at the Barc de Boutteville gallery in Paris and at the Kunstkring in The Hague, with the Belgians and Germans also prompt to feature his work. But this interest, soon to become demand, had to be managed. Between 1900 and the major retrospective of more than 400 works in 1905, staged at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, there were 15 exhibitions, all requesting loans. Dealers such as Ambroise Vollard in Paris and Paul Cassirer in Berlin negotiated to buy work, and surreptitious attempts by both the Bernheim-Jeune gallery and the wealthy Helene Kröller-Müller to acquire the whole collection needed to be thwarted.

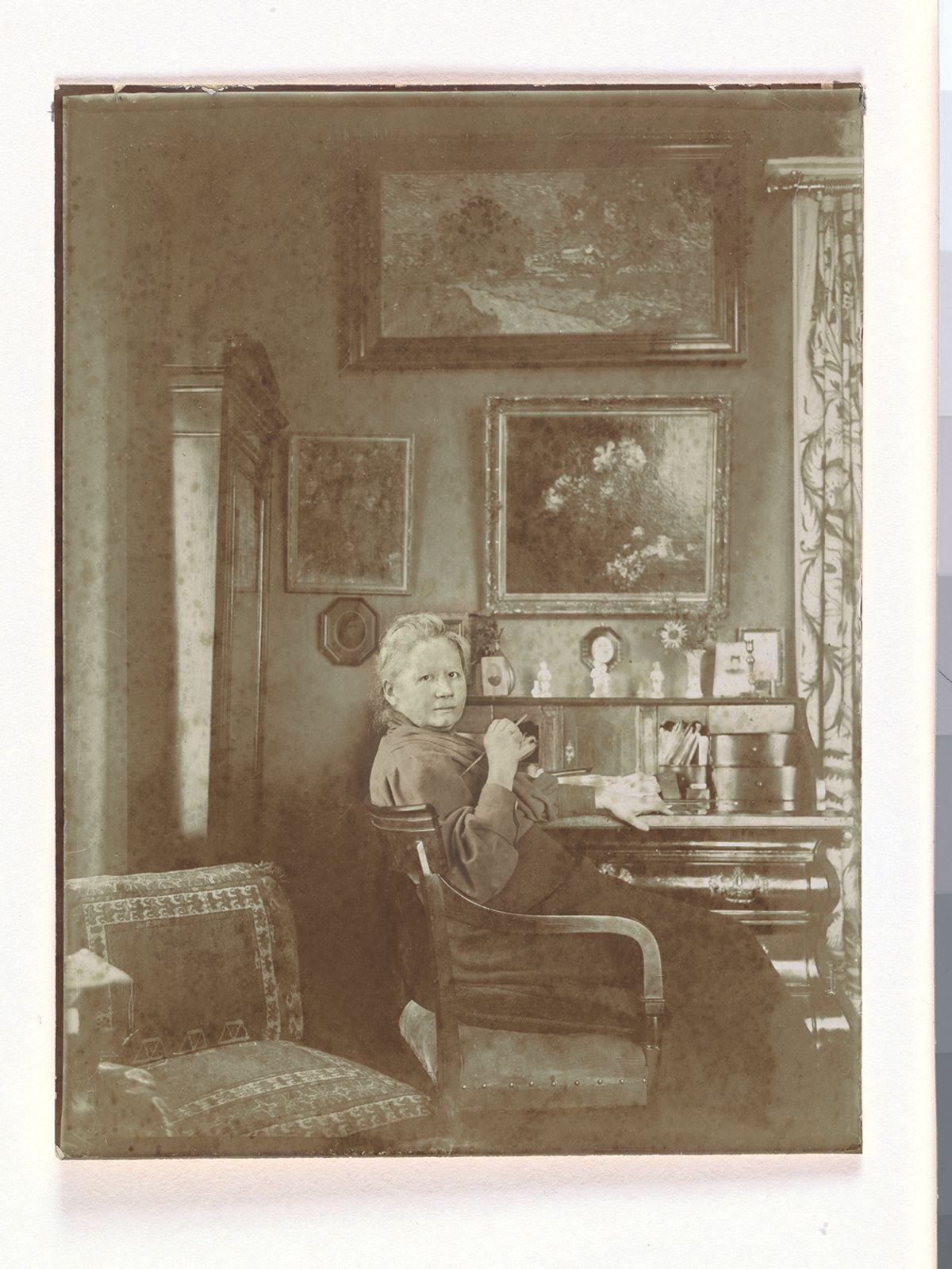

This practical and prudent Dutch bourgeoise orchestrated the posthumous fascination with her late brother-in-law’s life and work

The biography is in many ways the story of how this practical and prudent Dutch bourgeoise orchestrated the posthumous fascination with her late brother-in-law’s life and work. Van Gogh-Bonger felt a duty to both Vincent the artist and to Theo her late husband, and wanted to make the world aware of their fraternal bond, in honour of her short but happy marriage and also to provide funding for the young Vincent. By the time of her death in 1925, she had sold almost 200 paintings and more than 50 works on paper, still leaving enough for her son to found the Van Gogh Museum, which opened in Amsterdam in 1973.

An educated woman who had taught English and translated novels for Dutch newspapers, Van Gogh-Bonger was aware that their correspondence brought the dead alive. In 1914 she published Vincent’s letters to Theo in three volumes and by the time of her death had translated two-thirds of the artist’s letters into English. A serious personality with little sense of humour, her later relationships were not so successful, first with the libertine artist Isaac Israëls and then in her second marriage in 1901 to another painter, the neurotic Johan Gosschalk. We learn that Van Gogh-Bonger was motivated by her pious Protestant upbringing but also modern currents; she was a founder member of the Dutch Social Democrat Worker’s Party in 1894 and a strong proponent of women’s rights.

Luijten was one of the editors of Van Gogh’s correspondence, published in 2009. His indomitable research in the archives brings Van Gogh-Bonger fully to life, citing school reports, her diary and when she first rode a tricycle. There is much new material, such as the hundred letters Israëls wrote to her, and extensive footnotes in the original languages with English translations. A dutiful and determined woman has been matched with an altogether apt biography.

• Jo van Gogh-Bonger: The Woman Who Made Vincent Famous, by Hans Luijten, translated by Lynne Richards. Published 3 November by Bloomsbury Publishing, 544pp, 63 colour & 67 b/w illustrations, £20 (hb)