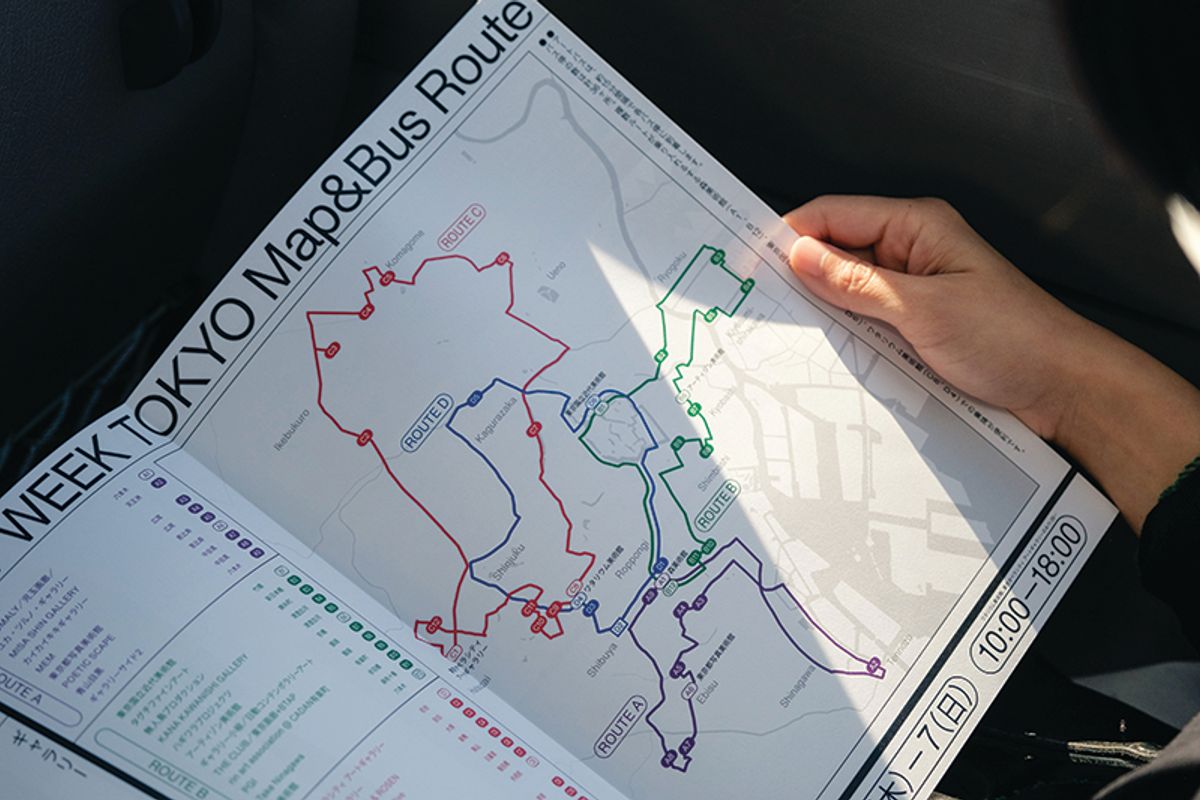

Art Week Tokyo (AWT), held in partnership with Art Basel, holds its second edition this month (3-6 November), incorporating more than 50 museums and commercial galleries spread out across the entire metropolitan area, from Roppongi to Tennozu Isle. AWT’s soft launch took place last year amid Covid-19 travel restrictions and welcomed more than 20,000 visitors. Its return comes as Japan opens its borders to individual vaccinated tourists on the visa waiver programme.

Since last year, Japan has been making a concerted effort to revive its standing as an international art hub, a peak unscaled since the country’s art market meltdown in the late 1990s. In a bid to attract fairs, auction companies and galleries to its freeport zones, regulations were eased in February 2021 for import procedures, duties and taxes for those areas, which typically amount to millions for high value art.

Right on schedule then, a new fair was announced earlier this year. Tokyo Gendai will run from 7 to 9 July 2023 in the expansive Pacifico Yokohama convention centre. Its imminent arrival coincides with a significant increase of sales through auctions, both in number of works sold and increase of bidding prices, especially with Tokyo-based SBI Art Auction, which specialises in contemporary works.

“Around 2017 to 2018, the number of exhibitions that would completely sell out started to increase. At the same time, international street art such as KAWS, Banksy, Invader, began to soar in price at local auctions,” says Satoru Arai, director and co-founder of Gallery COMMON in Harajuku. "The prices of young Japanese artists such as Tomoo Gokita, MADSAKI, Kyne, Rokkaku Ayako, Tide also began to rise," he adds.

So what’s behind this tectonic shift? Shinji Nanzuka, the owner of Nanzuka Underground, a contemporary art gallery in the Harajuku district that is taking part in AWT, describes a mass popularisation of art driven by younger generations and centred on the fusion of art and fashion. It began to gain visibility in 2018 but can be traced back to the late 90s, he says, when high fashion labels designers began collaborating with street artists such as KAWS and the famous Japanese artist Takashi Murakami.

According to industry figures, this upsurge of young collectors mostly comprises those with lucrative enterprises listed on the stock exchange, specifically in the field of IT.

Online shift

They are also part of a larger trend across Asia, where young collectors, heavily reliant on online communication via social media and unfussed about distinguishing between viewing art on a screen rather than in person, have been driving a shift to online sales both prior and since the pandemic.

Another AWT participant, Sueo Mizuma, whose eponymous art gallery has outposts in Tokyo and Singapore, welcomes the new wave of collectors. But he also observes that the art they seek to purchase is not necessarily predicated on the foreknowledge of contemporary art theory and art history.

“Many of these collectors are not aware of the significant part of Japanese art history such as Mono-ha or Gutai works,” he says. “They often base their decision purely on the current trend and popularity seen through social media, which tend to be 2D or illustration-style works that are hard to grasp just by viewing them online and most times have no strength when actually viewed in person.”

However, others such as Nanzuka view this new generation of collectors as part of “the democratisation of art in Japan in that the formerly closed art market has become more open”.

Acknowledging that the younger generation’s perception of art as a commodity may lead to the commodification and speculation of art, which could be critical, he believes they also serve as a trigger to break down the walls of “Japan’s conservative and authoritative art scene”.