For 84 years, one of Yale University’s residential colleges was named for former US vice-president John C. Calhoun, a Yale graduate who was an ardent supporter of slavery. But in July 2017, in a turnabout, the school officially dropped Calhoun’s name, denouncing him as a white supremacist, and elected to instead honour another alumnus, the pioneering computer scientist and mathematician Grace Murray Hopper.

The name change occurred amid a multi-year reckoning with Calhoun’s legacy that came to a head in 2016 when Corey Menafee, a Black dining-hall worker, smashed a stained-glass window in the college that depicted enslaved people picking cotton—one of several in a series that glorified the antebellum South. Now, following lengthy discussions about the college’s history, present and future, the university has permanently replaced a dozen windows in the building with ones designed by artists Faith Ringgold and Barbara Earl Thomas.

Commissioned by Yale, the new windows commemorate various communities on campus, from students to staff, while also acknowledging the school’s ties to racist practices. Thomas’s six designs are installed in the college’s dining hall, replacing problematic windows including the one Menafee had smashed. Ringgold’s six are in its common room, replacing an entire set of windows that were a visual timeline of Calhoun’s life.

Stained-glass panels by Faith Ringgold at Hopper College, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Courtesy Yale University

“We had two missions,” says artist Anoka Faruqee, associate dean at the Yale School of Art, who chaired a committee in charge of the window commissions. “To confront, not erase, the history of slavery in the United States, and Yale and Calhoun’s connection to it, and to celebrate and honour the legacy of a brilliant thinker and mathematician, Grace Hopper.”

The committee, formed in 2017 and comprising faculty, staff and students, selected Ringgold and Thomas through a nomination process. Members considered nominated artists’ relationships to storytelling and the content of their work, and how they may have addressed the history of racism in the US, according to Faruqee. “Faith Ringgold was basically the first artist we reached out to,” she adds. “Faith’s long career working in a variety of media, including quiltmaking and children’s books, was something that drew our attention, and her commitment to storytelling and forms of art-making that exist outside of a kind of rarefied art world.”

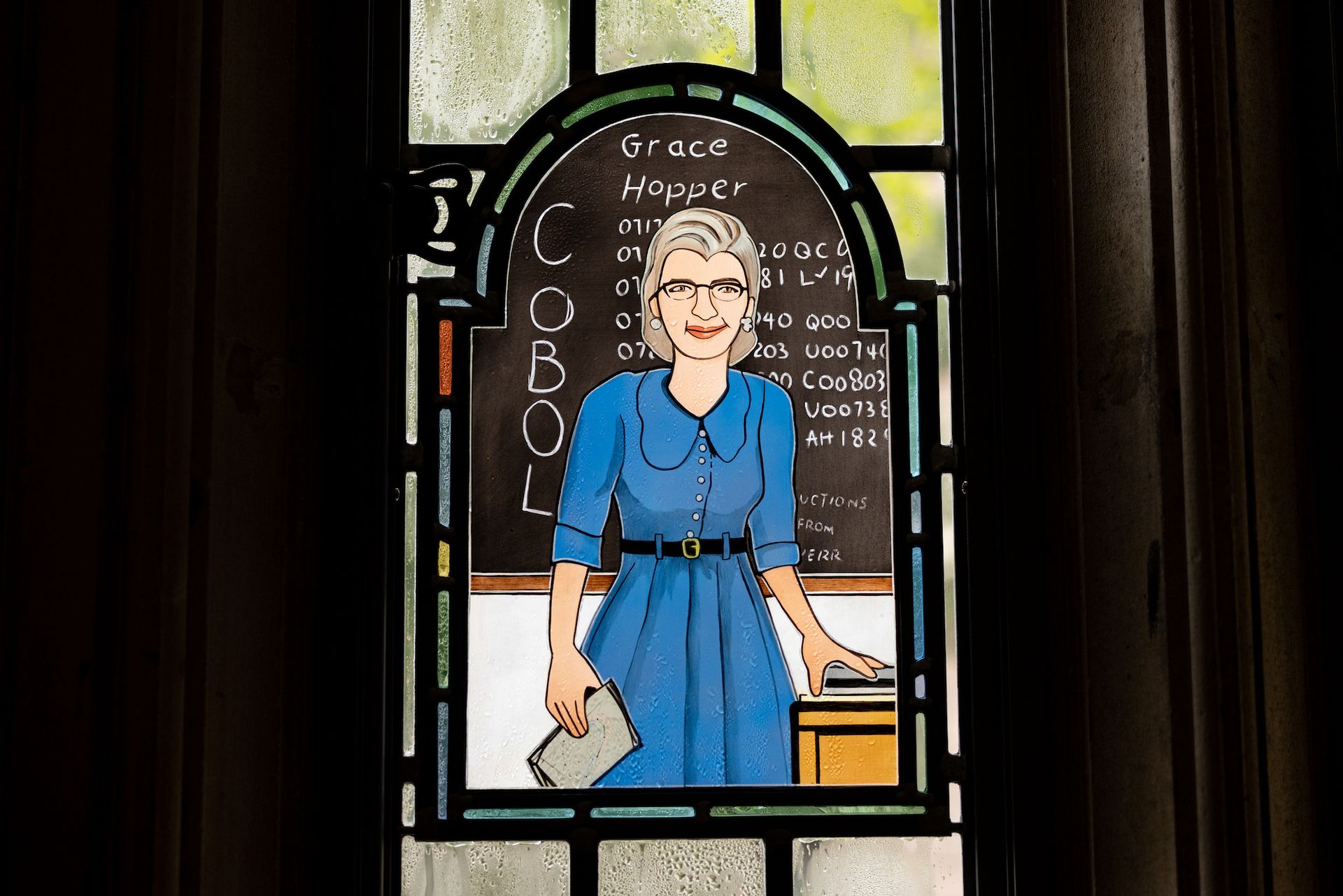

A stained-glass panel by Faith Ringgold at Hopper College, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, honouring the college's namesake, mathematician Grace Murray Hopper Courtesy Yale University

Designed in vivid colour, Ringgold’s windows portray scenes of student life, from a potter seated at a wheel to a group playing basketball outdoors. One pays tribute to Hopper, who taught at Vassar College before being appointed as a research fellow at Harvard University, in front of a chalkboard inscribed with the letters COBOL—referring to the standardised programming language she co-developed.

Thomas, too, commemorates Hopper’s legacy in one of her glass medallions, titled The Winds of Change. In it, a robin flies away with a banner bearing Calhoun’s name, while a hummingbird brings another banner with Hopper’s name to the foreground. “Calhoun’s name is in its correct place in history—in the background,” Thomas says. “What I wanted to do, number one, was tell the story of the name change in a way that honoured all of the people who struggled and made their voices heard—the students, faculty and staff who really were in these very energetic conversations . . . I was not there raising my voice, but I understood the movement, and I understood the earnestness the students were bringing to their effort.”

Stained-glass panels by Barbara Earl Thomas at Hopper College, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Courtesy Yale University

Another one of Thomas’s medallions arose from her discussions with Yale students who wanted to ensure that new windows celebrated the college’s maintenance and kitchen staff. The resulting design, titled From Kitchen to Table, shows four workers standing in the dining hall and is meant to emphasise the centrality of campus workers to student life.

Thomas, who is best known for her intricate, cut-paper portraits of Black life, has been working with glass since 2013. She brings a similar sensibility to both materials, engaging them to create strong graphic lines that she says were essential to a project like the Yale windows, given that the final works were ultimately installed high above eye-level. Light is also a key component of her works: she often replicates its effect through renderings of silhouettes, or literally illuminates delicate layers of her large-scale installations.

A stained-glass panel by Barbara Earl Thomas at Hopper College, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Courtesy Yale University

As part of her Yale commission, Thomas had an idea to create metal works reminiscent of light boxes to flank her windows. In November, handlers will install inside two stone niches two filigree portraits of Hopper and Roosevelt L. Thompson, a beloved Yale student who died in a car accident his senior year, and for whom the dining hall is named. Each portrait will be backlit at night to cast shadows around the room. “That was my added opportunity to say something about this historic moment, the changes that happened at Yale in these last two or three decades,” Thomas says.

As for the windows that were removed, they are now kept at the university’s archives, where they are reminders of a past that is in many ways very much present.

“The removal of the vestiges of John C. Calhoun’s life has felt like some kind of lifting, some sense of change, acknowledgement on the part of the university of its history and its complicity with slavery,” Farquee says. “The art is one necessary piece of this, for me personally, of imagining and envisioning a different future. But it’s not the only piece of a journey toward justice.”