Rodney Graham, a polyvalent conceptual artist whose work ranged across many media but maintained an indefatigable balance of rigour and irreverence, died on 22 October. He was 73 years old and had been fighting cancer for the previous year, according to a statement released by his family.

Graham was born (in 1949), lived and died in Vancouver, a city whose renowned cohort of conceptually inclined photographers had an early and lasting influence on his work. He studied under Vancouver School members Ian Wallace and Jeff Wall, though unlike their cool, enigmatic imagery, Graham’s work quickly distinguished itself by its aspects of performance and provocation. In addition to photography, his practice expanded to incorporate sculpture, film, video and, especially in recent years, painting.

Rodney Graham, Vacuuming the Gallery 1949, 2018 © Rodney Graham, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

“When I started at the University of British Columbia, it was photo-conceptual. Conceptual art was the main focus. I come from a slightly more literary predilection so that was galvanising to me—the possibilities of art from a conceptual perspective,” Graham said in an interview for The Quietus in 2018. “I didn’t go through a painting phase, it was only later that I began looking at painting. I was always more on the Duchamp side than Picasso. It took a long time for me to start dabbling in painting but it’s something I very much enjoy doing.”

After exhibiting primarily at Canadian museums and European galleries in the 1970s and 80s, Graham made an indelible impression on the global art world at the 1997 Venice Biennale, where he represented Canada with the comic film Vexation Island (1997). Like many of his still and moving image works, the film stars Graham, in this instance dressed in costume as a shipwrecked 17th century mariner with a bloody injury on his forehead. For much of the film’s nine-minute run he lies unconscious in the sand, finally waking up, shaking a nearby palm tree and being knocked unconscious by a coconut, shortly after which the film loops.

His star turn in Venice was followed by solo exhibitions at Canada’s National Gallery (in 1999), the Dia Art Foundation (2000), Hamburger Bahnhof (2001), the Whitechapel Gallery (2002) and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (2004). In 2017, the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead opened a major retrospective of his work. Vexation Island’s mix of sysphisian gravitas and slapstick humour, all rendered with superb production values, was typical of the films, videos and large-format, back-lit cibachromes Graham would make for the next quarter-century. He was often the main character in his compositions, sporting elaborate costumes, makeup and prosthetics—transforming him into a mid-century art dealer, a 1960s university professor, a dejected AbEx painter, an exuberant hippie, a cowboy outlaw and more.

Rodney Graham, Central Questions of Philosophy, 2018 © Rodney Graham, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

“We’ve lost our dear Rodney, a genius artist, dear friend, master of disguise, snappy dresser, supplier of dry humour, an amazing songwriter, always modest, an understated intellectual, gifted amateur, professional connoisseur, Sunday painter who seldom worked Sundays, ultimately a true professional in every sense of what it means to be an artist,” Nicholas Logsdail, the founder of Lisson Gallery, said in a statement. (Graham showed with Lisson, 303 Gallery, Hauser & Wirth, Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle and Esther Schipper.)

In addition to his wide-ranging artistic practice, Graham was a lifelong musician, regularly releasing classic rock songs with his Rodney Graham Band, though he regarded the project as a hobby.

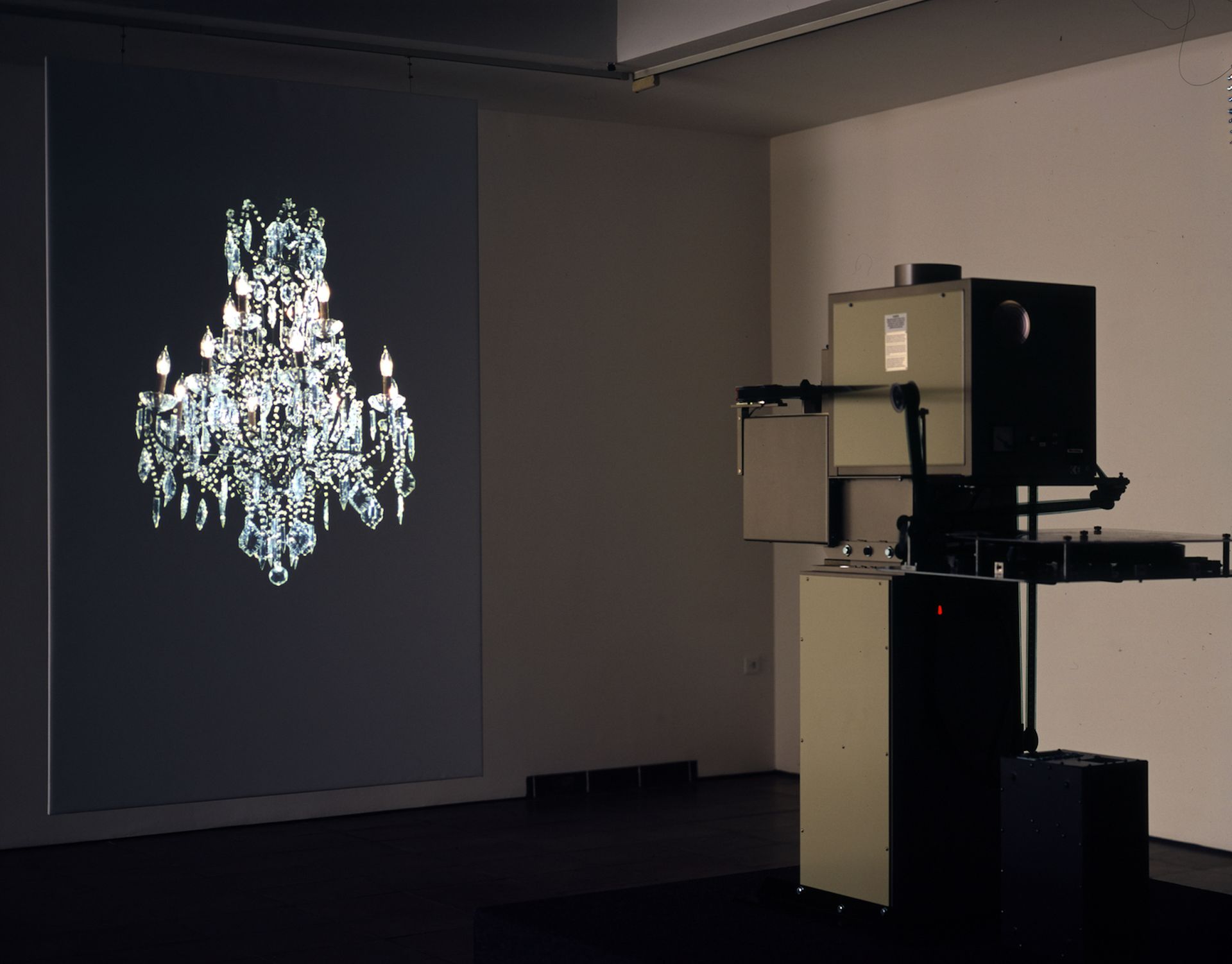

Rodney Graham, Torqued Chandelier Release, 2005 © Rodney Graham, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

In 2019, a $3.6m public art installation debuted in his hometown, ruffling some feathers and making manifest a chaotically spinning chandelier that appeared in one of his films. That work, Spinning Chandelier (2014), now lights up, descends from a bridge over Granville Island and spins for four minutes three times every day. Graham explained his desire to reach a wider audience with his work in a typically playful, earnest answer to a question about his recent series of works focused on artists in their studios during a 2013 interview with Flash Art.

“I guess this happened quite suddenly—a mystical epiphany in Venice when I saw that big polychrome sculpture of Jeff Koons having sex with his porn star girlfriend and member of the parliament. He really raised the bar. I thought it was time to ramp it up,” he told Flash Art. “I think works like this made a lot of people feel ineffectual, like Pete Townsend and Eric Clapton when they first heard Jimi Hendrix! I think I made Vexation Island after that, which involved a lot of financial speculation on my part. I put everything I had into it, and it ended up being a success. It was a very exciting time and I became converted to making works with more popular appeal.”