Performance art is a medium that is intrinsically tied to the moment. But as its practitioners mature, and the art world they occupy professionalises and expands, the question of their legacy grows bigger. For some late-career performance artists—and those already deceased—this is where a market for ephemera and documentation of their work emerges as a means to sustain their practice and keep interest alive.

Such is the case for Kembra Pfahler, a 61-year-old US filmmaker and performance artist who is represented exclusively by Emalin gallery in London. Pfahler was the subject of a recent exhibition held for the third edition of Performance Exchange, an annual London initiative that stages commercial exhibitions with partner galleries of performance-based artists. Key to Performance Exchange’s mission is to elucidate the practicalities of buying performance—both for private and institutional collectors.

However, Pfahler’s London show involved no element of performance as the artist was unexpectedly unable to travel to London, her gallerist Leopold Thun says. This was partly because she was also staging a performance in Florence that same month; the likelihood of performers being able to stage multiple international shows decreases as they age, Thun adds.

Growing value of ephemera

Luckily, then, since signing to the gallery in 2016, Pfahler has seen a sharp increase in sales of ephemera and documentation of her performances with her death-rock band, The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black. Previously, Pfahler worked with Jeffrey Deitch gallery but was not signed to its roster. For her recent show at Emalin, the gallery exhibited a series of never-before-seen collages made as posters or announcements for the artist’s performances in the 1990s across New York’s underground scene, priced between $5,000 and $15,000. Photographs of the artist’s more recent performances are also for sale through the gallery and were exhibited there for a 2019 show. These bodies of work are the only material ways in which collectors can buy aspects of Pfahler’s performances, as she does not allow sales or even re-creations of her live actions. Thun says that this decision reflects an element of a “generational divide”, as Pfahler comes from an era of artists who are not accustomed to thinking about their performances as standalone works or ones that could be commercialised. But this decision, he adds, is also intrinsic to the unique nature of her performances.

There is not a single banner [by Ana Mendieta] left; they were all likely destroyedMary Sabbatino, Galerie Lelong

Of course, not all performance-based artists who came up in the latter half of the 20th century were averse to having their live work re-created. Some actively sought it out, as in the case of Ketty La Rocca, an Italian artist who made performance works from the late 1960s until 1976, when she died of brain cancer. Her estate is handled exclusively by the British dealer Amanda Wilkinson, whose eponymous gallery also took part in this year’s edition of Performance Exchange, staging a work of La Rocca’s that was never executed in her lifetime. The work (In principio erat verbum, c.1970-72), which is being sold for €15,000 in an edition of three, contains a set of instructions for participants to communicate with one another through physical gestures.

At this year’s edition of Performance Exchange, Amanda Wilkinson gallery staged a show choreographed by Ketty La Rocca but never performed in her lifetime Courtesy Amanda Wilkinson, London and Ketty La Rocca Estate

La Rocca’s performance work can be purchased and re-created, but it faces another problem: there is not much of it. Despite being prolific during her active years, her body of work is small. This is why photographs that La Rocca took of her performances have found a strong market among both private and institutional collectors such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and Centre Pompidou in Paris. These photographs—sold for around €7,000 and editioned by the artist’s estate—are not only cheaper than buying a performance or a collage work, but are also one of the few means of accessing her performances, acting as a window into “a rare and increasingly critically fêted body of work”, Wilkinson says.

“La Rocca’s artistic practice was very much about a generosity of interpretation, which lends itself to re-creating performances. But not all artists are like that,” says Rose Lejeune, the founder of Performance Exchange. LeJeune, also an adviser, says this may be the biggest divide in late-career performers who are thinking about their estates. “It boils down to how one should think about the performance element of an artist in their wider work once they’ve died,” she says. “Do I want to make a purely archival estate, or do I want the performances to live beyond me?”

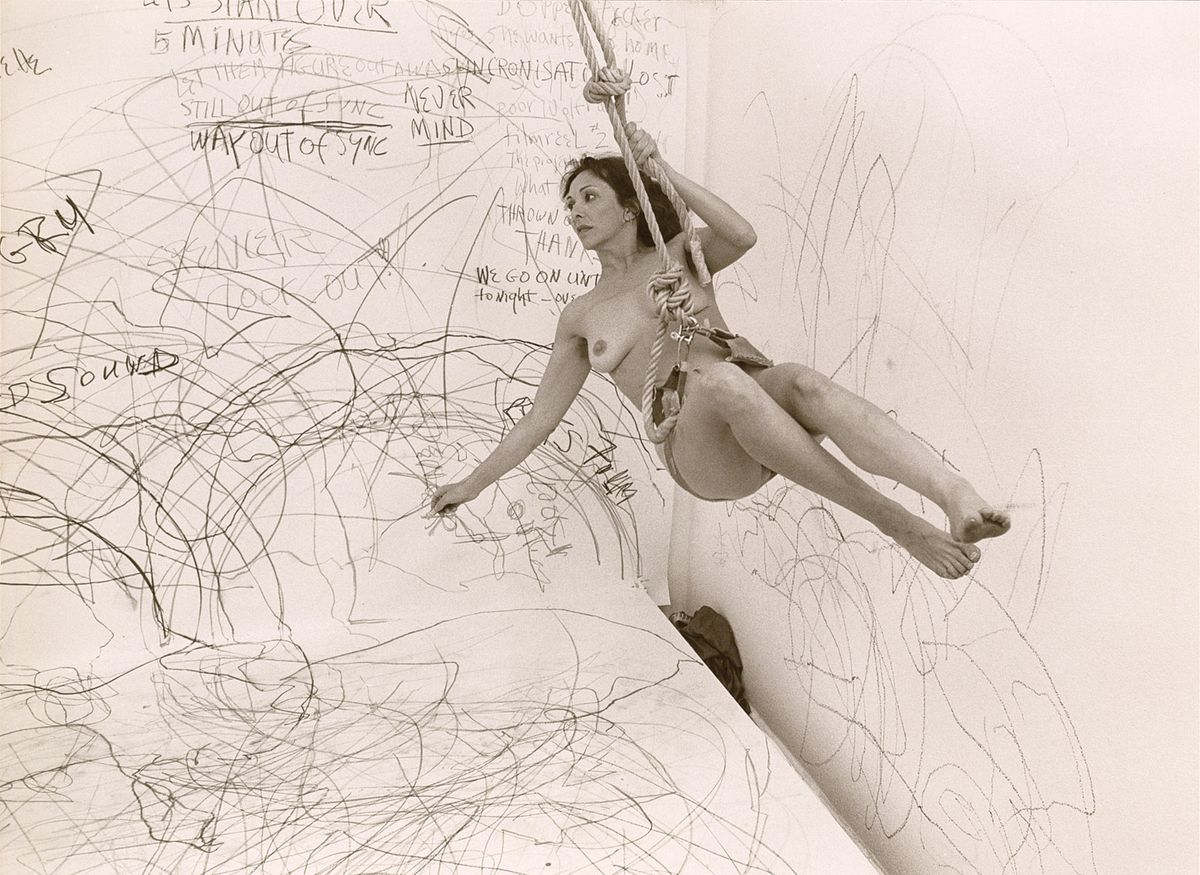

This question is germane when considering Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019), whose Barbican show, Body Politics (until 8 January 2023), has placed the artist back into the spotlight. The exhibition presents Schneemann as a radical figure who used her body to make political statements. Central to the exhibition are a number of her most famous performance works such as Meat Joy (1964), in which eight participants covered in paint, paper and paint brushes crawled and writhed together, playing with raw fish, meat and poultry, and Interior Scroll (1975), in which she pulls a scroll of paper out of her vagina. These are documented via Super 8 films and a few photographs from the artist’s foundation, which are not sold.

Carolee Schneemann with Venus Vectors (1987) Photo: Victoria Vesna; Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P.P.O.W, New York and © Carolee Schneemann Foundation / ARS, New York and DACS, London 2022

This is, according to Wendy Olsoff of PPOW gallery in New York—the primary dealer working with the artist’s estate–because Schneemann was determined to not be thought of as a performance artist. “Carolee wanted to be known as a painter. In her eyes everything about her practice boiled down to painting,” Olsoff says. The gallery will have three early paintings by Schneemann at its Frieze stand—dated from 1959 to 1962. While Schneemann did not specify that her performance works could not be re-created, she preferred to focus on the legacy of her painting, Olsoff says: “Everyone wanted to re-create Meat Joy or Interior Scroll; I think she was tired of that.”

Remaining ephemera from Schneemann's performances, such as the paper from Interior Scroll, are kept by the estate and “will never be sold”. Nonetheless, there are instructions for performances that are drawn over and have “turned into art objects” that PPOW also sells, Olsoff says. But due to the gallery’s focus on Schneemann’s painting practice, they form a less significant part of her market. Similarly, the performance work of David Wojnarowizc (1954-1992), another artist whose estate is handled by PPOW, was not well documented as “he was on death’s door when he made them”, Olsoff says, referring to his Aids infection from which he died. The exceptions to this are photographs and a voice recording made by the musician Ben Neill in 1989, which have been purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Julia Stoschek Collection and the Zabludowicz Collection.

Ambivalent performers

The ambivalence towards performance held by some artists who are ironically known best as performers is exemplified by the late Cuban American artist, Ana Mendieta. According to Mary Sabbatino, the vice president of Galerie Lelong, which deals with the artist’s estate, extremely little of the ephemera and objects from Mendieta’s well-known performances exist. A series, Body Tracks (1982), saw the artist dip her arms in blood and then solemnly walk on a silk banner. “There is not a single banner left; they were all likely destroyed,” Sabbatino says. “When I spoke to Mendieta’s frequent collaborator and friend, Hans Breder, he told me: ‘We didn’t think they were important to keep.’ Could you imagine how historically important they would have been if they’d been retained?”

Nonetheless, photographs of Mendieta’s Land art works, in which she would form silhouettes of human figures in the ground, are arguably the biggest part of her market. The gallery is selling a 1980 photograph from her Silueta series for $65,000 at Frieze London.

Sabbatino is largely responsible for building Mendieta’s market, having begun to work with the artist’s estate shortly after her death in 1985. At that time it was “nascent”, Sabbatino says, and one of her greatest projects has been digitising the sizeable body of films that Mendieta shot—around two-thirds of which contain “performance elements” and live action. Thus far, the archive is around 75% complete and has toured to a number of US museums; Sabbatino hopes to establish a market for those works in the future.

Documenting performance practices retroactively, while necessary, is an onerous task. Olsoff says she hired two full-time employees just to work on archives. This is something younger performers contend with less because of an increased availability of digital technology, but also thanks to a shift in attitudes towards documenting and commercialising a performance. “Performers today have fewer qualms about selling works by and large,” Lejeune says. “There are many factors at play here, but a big one is that it is no longer possible to live cheaply in big cities, rent large spaces for performances and live well. Those days are long gone.”

But as with their predecessors, one size does not fit all performers today. For example, Paul Maheke, who last year at Performance Exchange showed a choreographed dance centring on his personal experience of sexual abuse, says he has declined several propositions to acquire or even document his performance works that he considers “impossible” to collect: “Their nature is very much tied to improvisation and the moment in which they existed,” he says. “These works live within them and nowhere else.”