When, in August, Michael Heizer’s vast Land Art installation, City, was finally declared finished, among the first people to congratulate the artist was his one-time gallerist Virginia Dwan. “I still believe today what I thought when Heizer began,” Dwan wrote. “That this work demanded to be built… I have been fortunate enough to witness this transformative sculptural intervention from the very beginning.”

This was no more than the truth. When Heizer set to work in 1972 on the massive earthwork, one and a half miles long and half a mile wide—nearly the size of the National Mall in Washington, DC—Dwan was not quite 40. When she died, she was 90. But her connection to City was more than merely one of faith and longevity.

It was a loan from Dwan that had allowed Heizer to buy the first parcel of land in Garden Valley, Nevada—around 160 miles north of Las Vegas—that he spent the next half-century shaping into the world’s largest contemporary work of art. Nor was City Dwan’s first act of largesse towards the man she described as being “like an animal with a badly hurt paw”. Three years earlier she had underwritten the $30,000 cost of Heizer’s first big earthwork, Double Negative (also in a remote site in Nevada) “pocket change for art today”, Dwan later told the New York Times. “I saw it only after it was finished. That’s how I operated. If I believed in the artist, I trusted him.” Both loans were later written off.

Both Dwan’s generosity and her reticence were part of the story. She was born in Minneapolis in 1931, the grand-daughter of John Dwan, a founder of the Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Company, later the multinational conglomerate 3M. If she downplayed her wealth—“I’m not the 3M heiress,’’ she liked to say, “I’m one of 18”—Virginia Dwan had come into a large inheritance when she turned 21. (In 1961 her father’s share of the 3M fortune was valued at $23m, about $230m in today’s terms.)

Dwan’s family moved to southern California when she was a child, and she studied art at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) before dropping out to marry a fellow student, the social psychiatrist Paul Fischer. By 1958 she was married to another psychiatry student, a Frenchman called Vadim Kondratief. This marriage, too, ended in divorce, in 1965. By then, though, Dwan had opened her first gallery, in the Los Angeles neighbourhood of Westwood—convenient for the UCLA medical school but far from the city’s modern art district of La Cienega.

If the location had been chosen to suit her husband, Dwan was all too aware of the problems of being a woman gallerist: she discouraged Kondratief from attending openings with her, lest visitors assume he owned the gallery. Gender was not all that set her apart from the Angelino mainstream. Peering through the window of the Galerie Rive Droite on a trip to Paris in 1960, she had seen the all-blue reliefs of Yves Klein. “His work was so invasive that the blue in a way came into you,” Dwan recalled. “Infinity also came into you. I was anxious to be around that work.” By May 1961 Klein was exhibiting at the Dwan Gallery in a monograph show called Le Monochrome.

The first bicoastal gallerist

It was a courageous move on Dwan’s part. “There was a certain chauvinism in America that American art was ‘It’ and that nothing that happened in France mattered any more,” she said later. This was particularly true in 1960s Los Angeles, described by one of Dwan’s contemporaries as being like Nebraska with a beach. Le Monochrome received no reviews at all. Undeterred, Dwan used Klein’s contacts with the French Nouveaux Réalistes to put on shows of work by Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle and Arman. If these left Angelinos either scratching their heads or alarmed—Saint Phalle’s first performance involved her firing a shotgun at a canvas decked out with hidden bags of paint—Californian artists found the Dwan Gallery a source of revelation. The painter John Baldessari, a visitor to Le Monochrome, recalled Klein’s reliefs as “defying everything I knew about art”.

Nonetheless, New York remained the epicentre of the US avant-garde. In 1965 Dwan opened a gallery, in Manhattan; in 1967, she shut the Los Angeles one. In the intervening two years hers was the country’s first and only genuinely bicoastal art venture. Typically, Dwan chose to open the New York gallery with a show by a Californian artist, Ed Kienholz.

Earlier, she had made a point of bringing Easterners out west, most notably in the form of Pop artists—Claes Oldenburg and Roy Lichtenstein among them—she had imported to Los Angeles for the 1962 show My Country ’Tis of Thee. The original Dwan Gallery had opened in 1959, the year that New York and Los Angeles were first connected by a regular jet service. Dwan’s artists, flying back and forth, looked down on the US from a height they had never experienced before, a vision that would feed into the aesthetic of the movement with which her name remains most strongly linked: Land Art.

Michael Heizer was not the only Land Artist to benefit from Dwan’s interest. In 1968, in New York, she put on the first ever exhibition of land-based art in a show called Earthworks. Among the artists in it were Heizer, Robert Smithson and Walter De Maria. In 1970 Dwan underwrote the building of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake, Utah; in 1974, the first version of De Maria’s fabled Lightning Field. De Maria had made a prototype of this for a solo show that Dwan had given him in her Manhattan gallery—a floor-based sculpture called Bed of Spikes. “I once checked to see if they really were sharp by touching my palms to the points,” Dwan thoughtfully recalled to an audience at Dia Beacon in upstate New York in 2003. “I got stigmata.”

For Dwan, one of her most satisfying New York exhibitions was 10 (1966), featuring a loosely associated group of artists that included two Minimalist pioneers, Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre. She would become closely associated with both. “Theirs were cool, quiet, still works,” she recalled. “I felt at ease, comfortable with them. Minimal art was totemic, in a way. It held its own energy within it.”

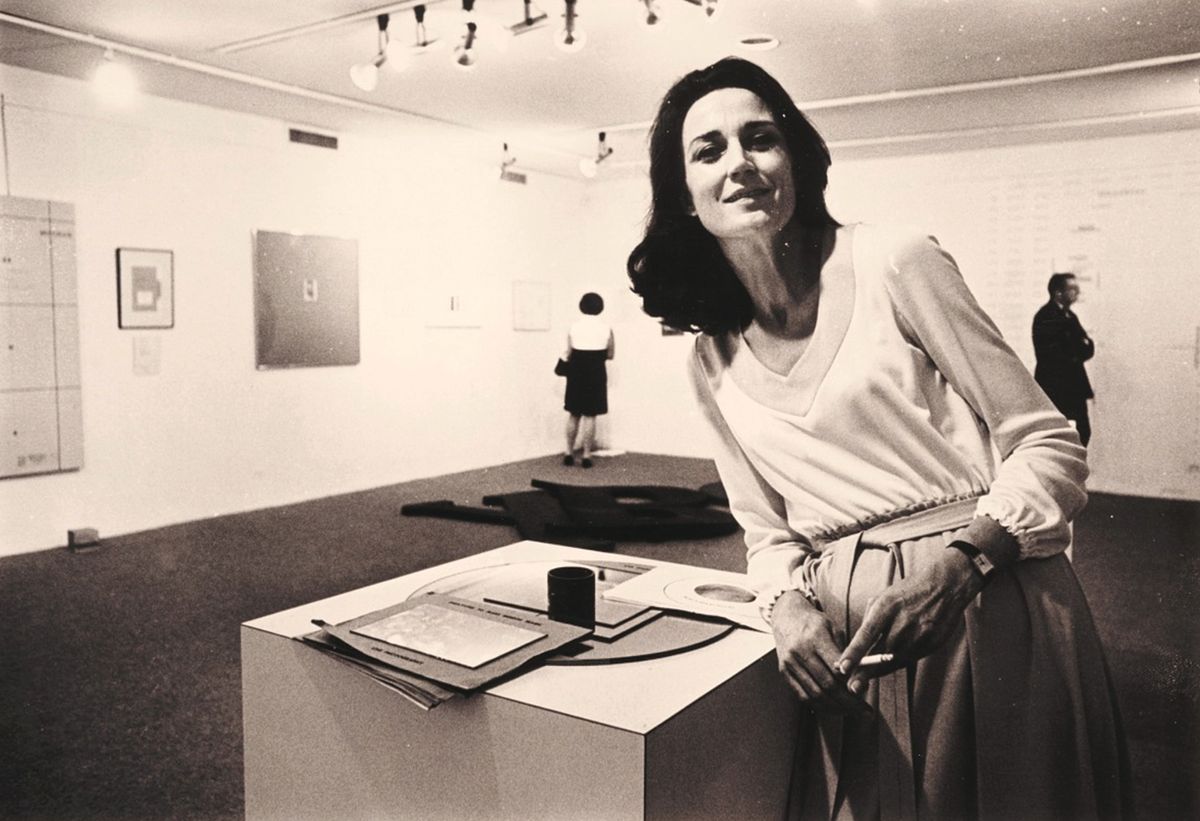

Dwan’s passion and acumen meant that her decision, in 1971, to shut her gallery came as a shock. Explaining it three decades later to the New York Times, she said, “It had begun to overwhelm me. I lost money from beginning to end, which was never the intention. I didn’t like collectors much. I hated selling.” Her subsequent disappearance from the narrative of modern American art history is harder to explain, and only now being addressed.

It was due, perhaps, to a lingering (and baseless) suspicion that Dwan was more a patron than a gallerist, her success down to wealth rather than devotion or prescience. Dubbing her, as one newspaper did, “a jet-age Medici” did her no favours. Closer to the mark was how Dwan was described by James Meyer, the curator of the show Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959-71, held in 2016 to mark the 2013 bequest of 250 pieces from her collection to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Dwan, Meyer said, was “a modern-day Durand-Ruel or Kahnweiler”. Half a century before, those legendary dealers had championed Impressionism and Cubism. Dwan’s early support for Minimalism and Land Art has proved no less historically important.

• Virginia Dwan, born Minneapolis 18 October 1931; married Paul Fischer (one daughter; marriage dissolved), secondly Vadim Kondratief (marriage dissolved); died Santa Fe, New Mexico, 5 September 2022.